Abbott’s Aromatic Bitters – A Later Bitters with Class

27 December 2011 (R•052914)

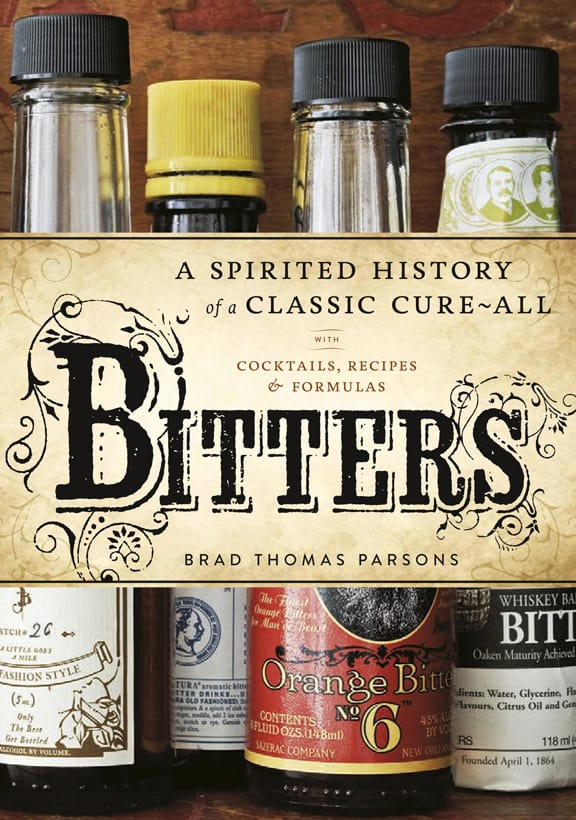

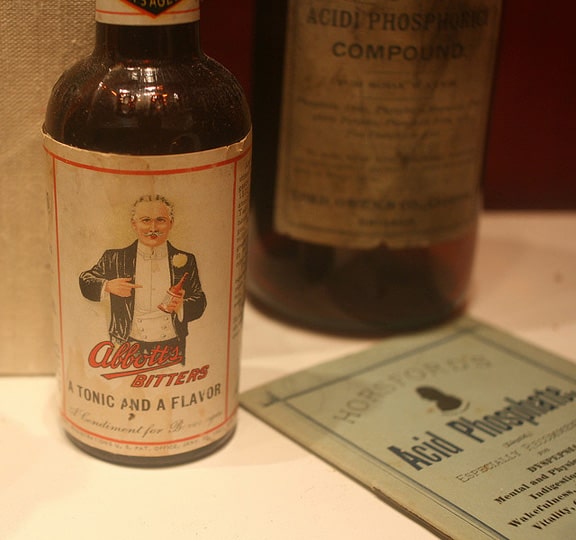

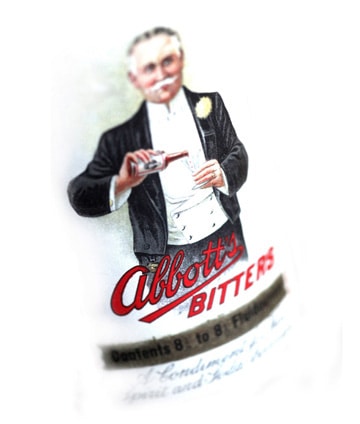

![]() In a separate area of my house and away from the gorgeous ‘heavy-hitter’s in my bitters collection sits the later bitters bottles. Many of these bottles are labeled and some contain original contents. It is for these reasons that they sit like the one legged ‘Tin Soldier’ away from my other toys. They are usually not ‘window’ bottles and need an area away from natural light to protect the contents and labels. So I ask, “why is this gentleman dressed in a tuxedo and what is he making”?

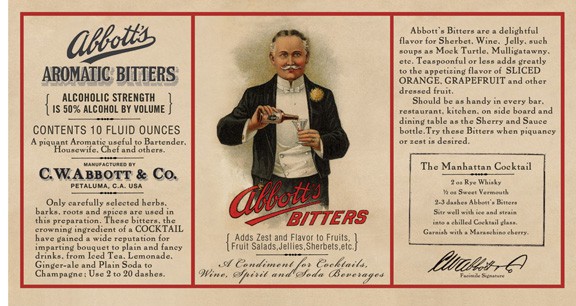

In a separate area of my house and away from the gorgeous ‘heavy-hitter’s in my bitters collection sits the later bitters bottles. Many of these bottles are labeled and some contain original contents. It is for these reasons that they sit like the one legged ‘Tin Soldier’ away from my other toys. They are usually not ‘window’ bottles and need an area away from natural light to protect the contents and labels. So I ask, “why is this gentleman dressed in a tuxedo and what is he making”?

“It is for these reasons that they sit like the one legged ‘Tin Soldier’ away from my other toys”

“It is for these reasons that they sit like the one legged ‘Tin Soldier’ away from my other toys”

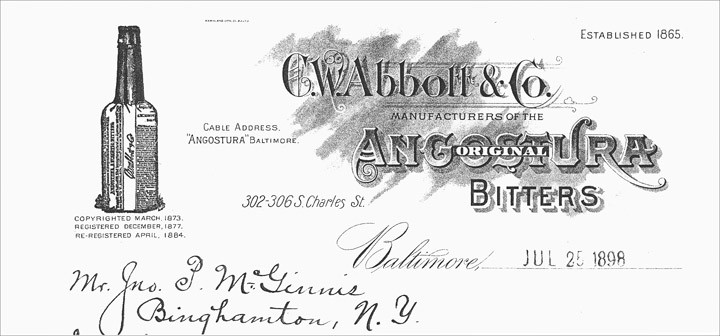

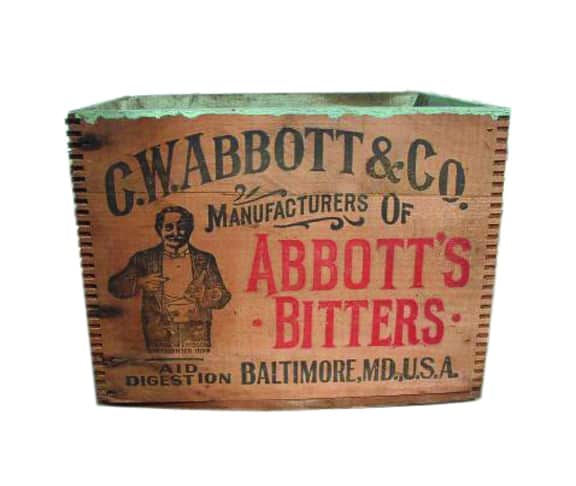

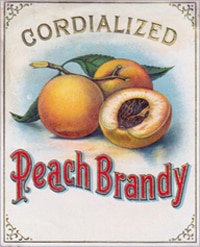

Today I would like to talk about Abbott’s Aromatic Bitters from the C.W. Abbott Company. C.W. Abbott and Co. was founded in 1865 in Baltimore, Maryland, which was then one one of the epicenters of American liquor production. Abbott’s began selling its bitters in 1872, becoming one of the three biggest-selling bitters (the other two being Angostura and Peychaud) during the cocktail era. It was also the bitter used in the original Manhattan cocktail. The company continued trading until the 1950s but then disappeared from the market.

This is a really nice write-up I found in Class Magazine (Words by Jake Burger and Robert Petrie)

Back in 1865, bitters had long been part of the bartender’s armory: at that point, it had already been some 59 years since The Balance and Columbian Repository had defined a ‘cocktail’ as “a stimulating liquor composed of spirits of any kind, sugar, water, and bitters – vulgarly called a bittered sling…”.

Back in 1865, bitters had long been part of the bartender’s armory: at that point, it had already been some 59 years since The Balance and Columbian Repository had defined a ‘cocktail’ as “a stimulating liquor composed of spirits of any kind, sugar, water, and bitters – vulgarly called a bittered sling…”.

By the mid-19th century, bitters might not quite have shaken off the perception of their being bed-fellows of snake oils, tonics and elixirs – with producers making fanciful claims about their ability to purify the blood, or to cure dyspepsia, malaria and constipation or to cleanse the liver – but business was good and bitters brands proliferated across the land. It was a golden age of drinking in America: Jerry Thomas had just written his Bartenders Guide; the foundations for recipes that we still use today were being established; and bitters were playing a key role. Their place in bartenders’ essential repertoire was further sealed in 1900 with Harry Johnson’s Bartender’s Manual in which he listed the principal bitters “required in a bar room” as Boker’s, Hostetter’s, Orange, Boonecamp, Stoughton, Sherry Wine, East India and Angostura. Abbott’s and Peychaud’s are curiously absent from his list, perhaps explained by the fact that he includes an advert for their nearest rival Boker’s, which would disappear, presumed bankrupt, just some three years later.

“Dressed with a cloak of respectability, Abbott’s survived this cull”

But there were two clouds looming on the horizon that would change America’s bartenders’ relationship with bitters for the rest of this story. Firstly, in 1906, Theodore Roosevelt created the Food and Drug Administration and signed The Pure Food & Drug Act. This required products that claimed certain health benefits to have proof to back it up. Dressed with a cloak of respectability, Abbott’s survived this cull, with a booklet of the era describing: “To the physician: As a menstruum or vehicle the physician will find Abbott’s Bitters lessens and prevents the irritation of Salts, viz.: Bromides, Iodines, and Salicylates; acts as a solvent and helps remove their flatness.” Or in layman’s terms: “You can dissolve medicine in Abbott’s and it will taste nicer.”

Secondly, around 1920 came the passing of The 18th Amendment and The Volstead Act: Prohibition had arrived. This was not immediately the death knell for bitters that you might imagine: due to the vestigual traces of respectability that their medicinal heritage imbued on them, bitters were exempt from the act and actually flourished throughout Prohibition. In fact it wasn’t Prohibition that tolled the death knell for America’s bitters tradition: though it can arguably be attributed to its abolition in 1933. With that, America’s distillers returned, with some vigour, to the task of producing bourbon and rye, and it seems that it was this gold rush for whiskey money which saw off all but a few brands of bitters. Producing bitters was just nowhere near as lucrative as hard liquor.

The bitters market was left with Abbott’s, Angostura, Peychaud’s and Fee Brothers – three of those you probably stock on your bar today, with Abbott’s having become victim to our old friends, The Food and Drug Administration, in 1954. It imposed a ban on tonka beans in food and drink due to their coumarin content – coumarin is a naturally occurring chemical that can lead to intestinal bleeding and liver damage. It was particularly damaging in rats, though less so in humans, who can metabolize it much better, but hey, Uncle Sam knew best. Unfortunately for Abbott’s, tonka beans provided the key flavour to its bitters, tasting something like a blend of vanilla, almonds and cloves.

We have heard anecdotal evidence that Abbott’s re-formulated the brand, perhaps using vanilla. That’s merely speculation: what is certainly true is that it was around this time that Abbott’s disappeared for good. Perhaps the new recipe meant they just weren’t as good as they used to be, or more likely the whole category was in decline as post-war America’s palate sweetened and embraced the tropical flavours of Tiki drinks – not really the natural home of a dash of bitters. Abbott’s was consigned to the dustbin of history.

Sadly, there was no recorded history of its formula and that, as they say, was the end of that. And so it remained for nearly 60 years, until five years into the 21st-century, when a group of cocktalian geeks would meet on Robert Hess’s Drinkboy forum to discuss everything that had been forgotton about the art of bartending and drinking. It was one of these fine fellows by the name of PerfumeKev who had the means to run a gas chromatography analysis on an unopened bottle of Abbott’s from the 1920s. By the wonders of modern science, the original formula for Abbott’s began to be revealed to us.

Around that time I (Jake) was fortunate enough to acquire a bottle of Abbott’s of a similar age, which I excitedly opened and proceeded to nurse for around four years, and when the bottle was running low decided it was about time to put PerfumeKev’s hard work to the test. It was also around this time that a mutual friend introduced me to one Robert Petrie, AKA the eponymous Bob of Bob’s Bitters. With a combination of the formula from PerfumeKev, the last few drops from the original Abbott’s, we set about improvising, guessing and, most importantly, conducting countless comparative tastings – read: a marathon of Manhattans – in a bid to recreate the original formula. Using the results of the gas chromatography analysis that had been carried out by PerfumeKev we already had a very rough guide to certain ingredients, but not their quantity. And because of the age of the bottle, which could be well over 80-years-old, we knew a lot of the more delicate ingredients would have deteriorated over the years, with the loss of flavour and complexity.

Over the next three-and-a-half years we questioned which, as well as why, certain ingredients were probably used in the original, deconstructing and reconstructing the results of the gas chromatography analysis. Not only did we conclude that Abbott’s was a carefully thought-out tonic in its day to aid digestion, we realised it could also have been used as a cough remedy, given its properties. Together, we found Abbott’s to be heavy on nutmeg and cinnamon, with a strong clovey note, and established a flavour profile based around 15 ingredients. Over the course of the three-and-a half-years a further 15 ingredients were slowly identified. These mainly had medicinal properties, with some selected ingredients added, that we felt would add more depth to the Abbott’s with underlying layers of flavour and aroma. As for the use of tonka beans, (still prohibited in America – though we understand under review), we tried substituting them with vanilla and almonds, but this resulted in a somewhat poor relation of the “real thing”. The next stage was to purchase a medium-charred American oak barrel, in which we aged the Abbott’s for six months, producing a more rounded, mellow-flavoured bitter with many layers of complexity.

Is our version of Abbott’s a faithful reproduction? As far as is possible to be: gas chromatography is not 100 per cent accurate and some flavours decay and disappear faster than others, so we added a few lighter floral flavours that we felt were appropriate but which may not have been in the original. Nobody can know for sure – but we are confident that it’s a pretty good approximation. Perhaps more importantly, by being the first people to commercially reproduce this holy grail of bitters and put it back in its rightful place, behind bars and in cocktail cabinets, we are proud that we have helped ensure that the name Abbott’s lives on for another day. To put it bluntly, a Manhattan made with original Abbott’s really is one of the finest drinks known to man, and we won’t mix our Manhattans with anything else. We think you should do the same.

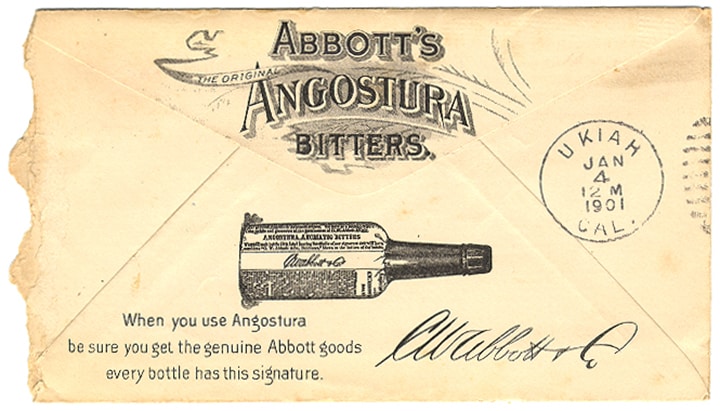

I have posted below some representative pictures and images…