PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND

A Glimpse at Providence Advertising in 1861-2

21 April 2013

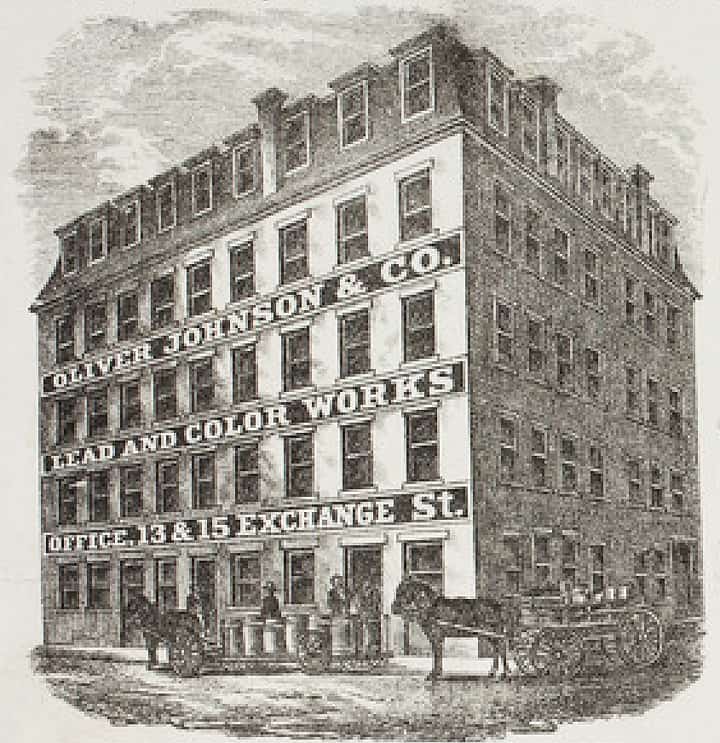

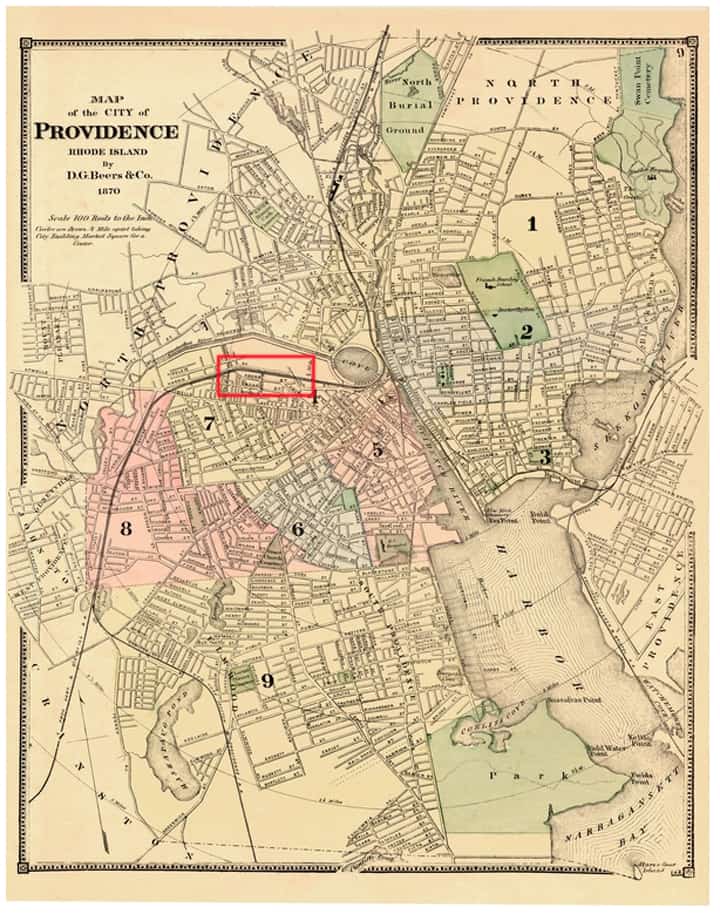

![]() I have to admit, I get side tracked real easily when looking up information on Bitters brands. In this case it was looking for information on Barber’s Indian Vegetable Jaundice Bitters put out by Oliver Johnson & Company in Providence, Rhode Island. Looking for advertising for the product in the 1860s, I was captured and intrigued by locating the company on a map (see below) of that period and by some of the other businesses that competed with Mr. Johnson with his advertising in the various Providence Business Directories of the period. This made me to wonder what else was happening in he 1860s in Providence.

I have to admit, I get side tracked real easily when looking up information on Bitters brands. In this case it was looking for information on Barber’s Indian Vegetable Jaundice Bitters put out by Oliver Johnson & Company in Providence, Rhode Island. Looking for advertising for the product in the 1860s, I was captured and intrigued by locating the company on a map (see below) of that period and by some of the other businesses that competed with Mr. Johnson with his advertising in the various Providence Business Directories of the period. This made me to wonder what else was happening in he 1860s in Providence.

Map of the City of Providence, Rhode Island – 1870 (Location of Oliver Johnson & Co.within red rectangle)

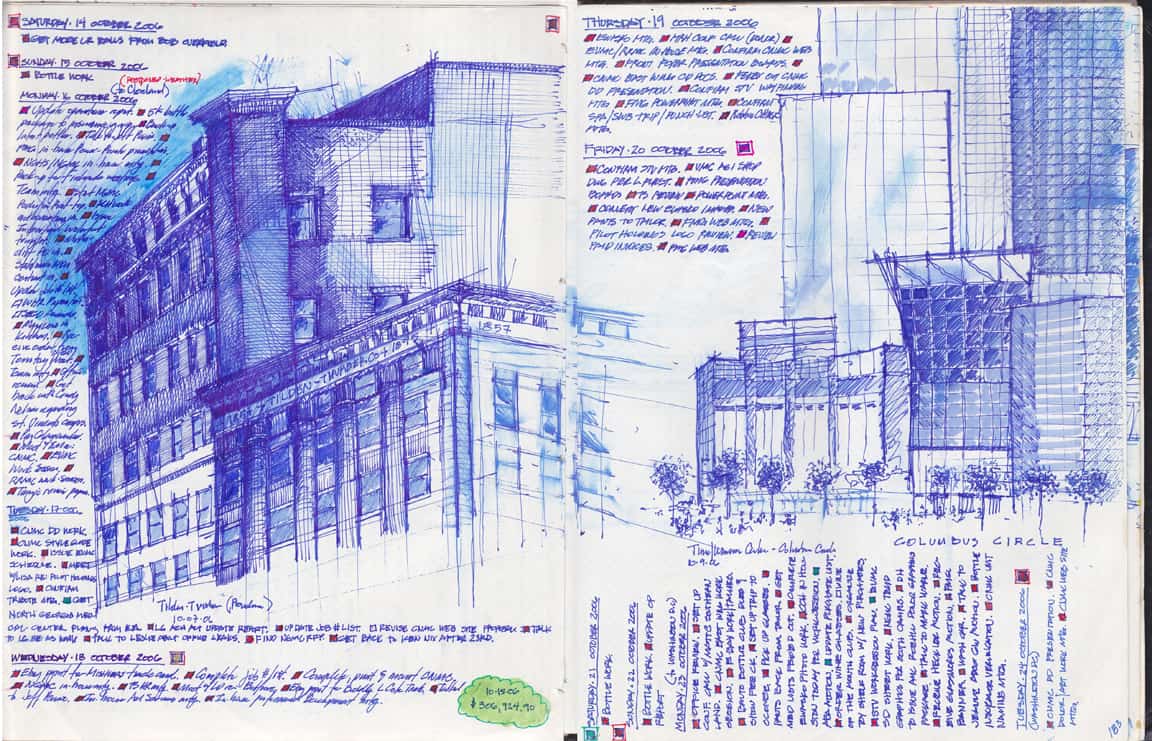

Providence is a great city full of history. On a few previous trips to the Heckler Columbus Day Hayfield event in Woodstock, Connecticut and the Yankee Antique Bottle Show in Keene New Hampshire we have managed to stay at the historic Hotel Providence downtown, visit some of the museums and look at the old architecture. I keep a journal, I have since 1975 or so and write and sketch just about every day. Below you will see two sketches from 2006 and notes from a visit to Providence prior to the shows and a visit to Columbus Circle of of Central Park in New York City after the shows.

Journal spread from 2006 showing the Tilden Thurber building in Providence (left) and the new Time Warner Center in New York City at Columbus Circle. View from Central Park – Ferdinand Meyer V journal 2006

Providence and Civil War: 1860-1868

Providence, like every city in America, felt the impact of the Civil War, but this was a war that many in Providence sought to avoid. Yankee businessmen, especially those producing cotton textiles, had economic ties with the South which war would(and did) disrupt. As some critics remarked, there seemed to be an unholy alliance between the “lords of the loom” and the lords of the lash,” as the slave holders were called. In addition, many foreign-born Irishmen, resentful that they needed land to vote while blacks were subjected to no such discrimination, had little sympathy for freeing those who could become their rivals for jobs on the lower rungs of the economic ladder.

Consequently, when the Republican party nominated Seth Padelford for governor in 1860–a man whose antislavery views were extreme–a split occurred in party ranks. Supporters of other Republican aspirants and Republican moderates of the Lincoln variety joined with Democrats (who were softer on slavery) to nominate and elect a fusion candidate on the “Conservative” ticket. Their choice, twenty-nine-year-old William Sprague, was heir to a vast cotton textile empire and a martial man who had attained the rank of colonel in the Providence Marine Corps of Artillery. Sprague outpolled Padelford 12,278 to 10,740, carrying Providence 3,578 to 2,761–victory celebrated as a rebuke to abolitionism by the citizens of faraway Savannah, Georgia, who fired a 100-gun salute in Sprague’s honor.

But if Providence and Sprague were soft on slavery, they were strong on Union. After the Confederate attack of April 12, 1861, on Fort Sumter, the local citizenry rallied behind their once-conciliatory governor and rushed to the defense of Washington. President Lincoln issued his call for volunteers on April 15. Just three days later, the “Flying Artillery” left Providence for the front, and on April 20 Colonel Ambrose Burnside and Sprague himself led 530 men of the First Regiment, Rhode Island Detached Militia, from Exchange Place to their fateful encounter with the rebels at Bull Run. More than half of Burnside’s regiment hailed from Providence.

During the war there were eight calls for troops, with Rhode Island exceeding its requisition in all but one. Though the state’s total quota was only 18,898, it furnished 23,236 fighting men, of whom 1,685 died of wounds or disease and 16 earned the Medal of Honor. Providence, with 29 percent of Rhode Island’s population in 1860, supplied nearly half its fighting men.

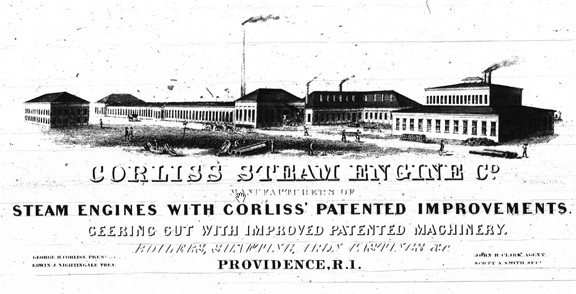

The city’s contribution to the Union victory went beyond mere military manpower. Some historians have claimed that the productive element in the outcome of the Civil War. Here again Providence was prominent. Its woolen mills, especially Atlantic and Wanskuck, supplied federal troops with thousands of uniforms, overcoats, and blankets, fashioned on sewing machines made by Brown and Sharpe, while metals factories such as Providence Tool, Nicholson and Brownell, and the Burnside Rifle Company provided guns, sabers, and musket parts. Builders Iron Foundry (established in 1822 and still operating in West Warwick) manufactured large numbers of cannon; the Providence Steam Engine Company of South Main Street (established 1821) built the engines for two Union sloops of war, the Algonquin and the Contoocook; and Congdon and Carpenter (established 1792) supplied the military with such hardware as iron bars, bands, hoops, and horseshoes from its factory at 3 Steeple Street (now the city’s oldest surviving industrial building).

On the home front, the Civil War decade was a time of continued growth and modernization for Providence. The city’s most important and dynamic mayor, Thomas A. Doyle, began a nineteen-year reign in 1864. He promptly reorganized the police department into an efficient, modern force and converted the Market House into a municipal office building.

City health and sanitation programs, under the capable direction of Dr. Edwin M. Snow, were models for other municipalities to emulate. Elsewhere in the field of medicine, the urgings of Dr. Usher Parsons combined with the philanthropy of Thomas Poynton Ives to establish Rhode Island Hospital, giving Providence a first-class medical facility at last.

In education, business and commercial schools such Scholfield’s and Bryant and Stratton flourished as they provided a growing white-collar work force with the office skills needed to administer the affairs of the city’s burgeoning industries. And in the public schools a momentous event, inspired by the outcome of the war, occurred in 1866: racial segregation was abolished both in the city and throughout the state.

It was during the Civil War decade that urban mass transit came to Providence. Its vehicle was the horsecar, a mode of travel over the streets of the city that combined the old (actual horsepower) and the new (iron rails). The horsecar lines, extending from the Union Depot in Market Square over the surface of every major thoroughfare, were essential factors in the growth and settlement of the city’s “streetcar suburbs”–the outlying neighborhoods of Providence that were reclaimed from the surrounding towns of Cranston, North Providence, and Johnston beginning in 1868. Closer to the city’s core, splendid mansions, built by the city’s business magnates, sprang up on the East Side and in the West End along Elmwood Avenue, Westminster Street, and Broadway.

With the war a partial stimulus, industrial Providence began to scale its greatest heights, pulled from above by its wealthy Yankee entrepreneurs and investors, pushed from below by a growing immigrant work force that now began to include migrants from Germany, Sweden, England, and French Canada. Together the titans and the toilers labored to make Providence an industrial giant among the cities of the nation. As the cataclysmic sixties rushed to their conclusion, the city rushed onward towards its Golden Age.

City of Providence, Rhode Island

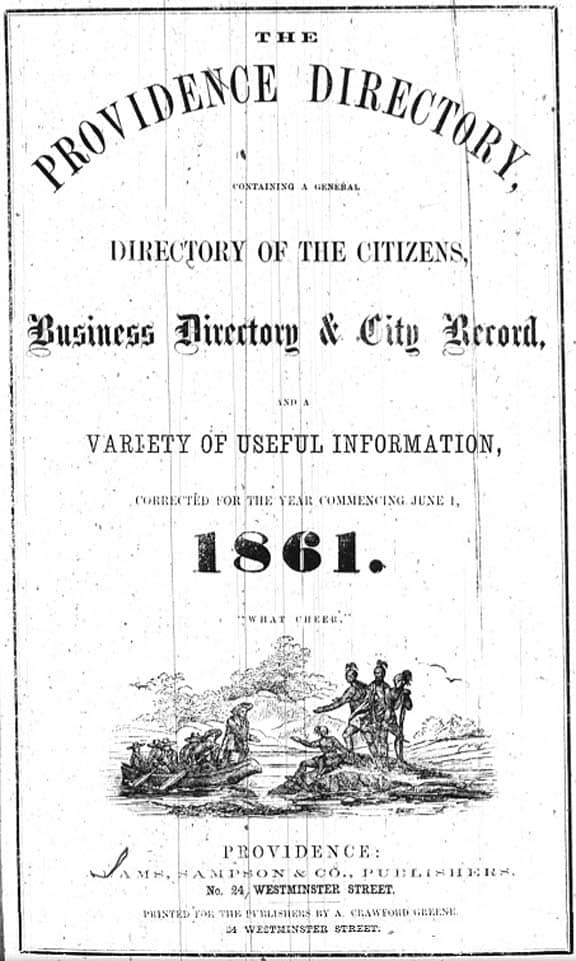

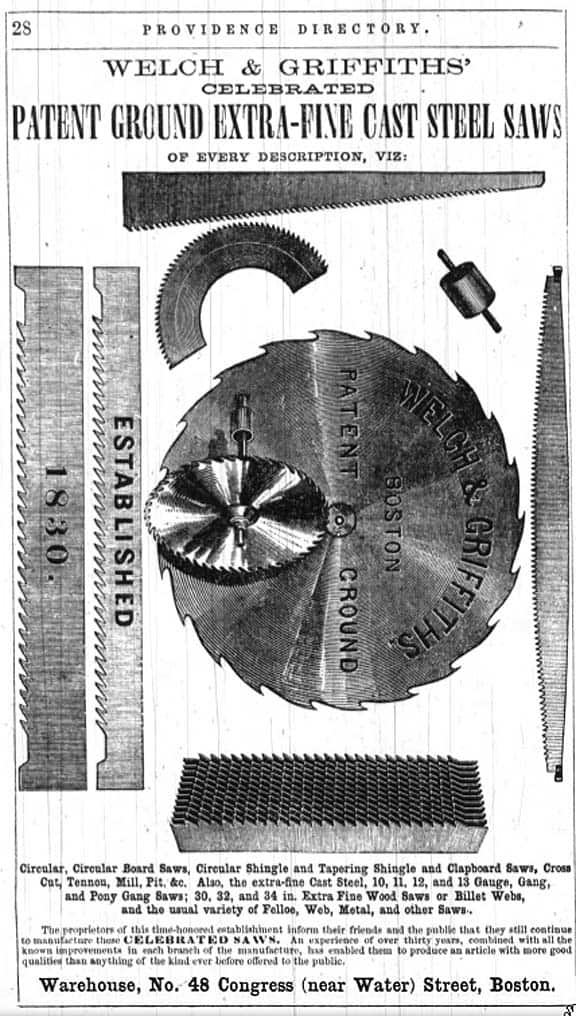

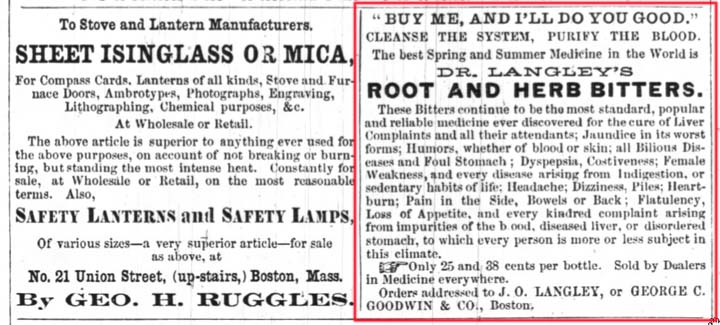

The Providence Directory | 1861-2

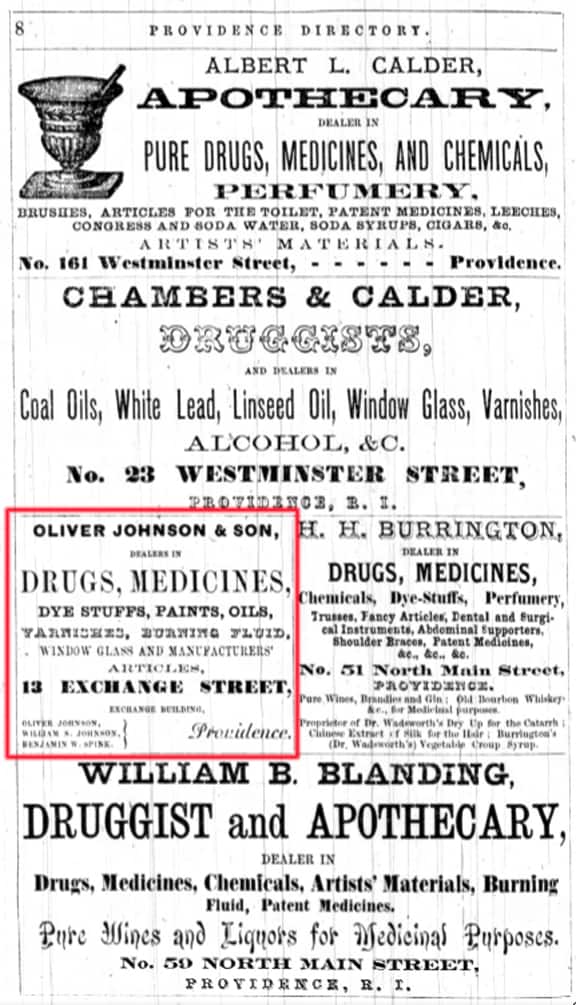

Providence Directory Drug Listings – 1862 (OliverJohnson put out Barber’s Indian Vegetable Jaundice Bitters)

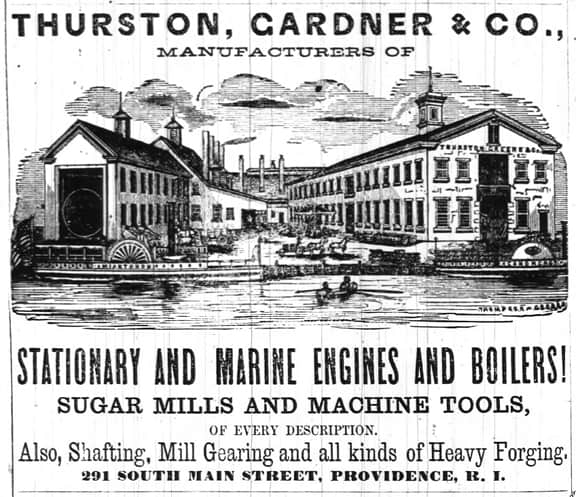

Thurston, Gardner & Co. advertisement showing theiroffices and warehouses on the waterfront. Providence Directory Listings – 1862

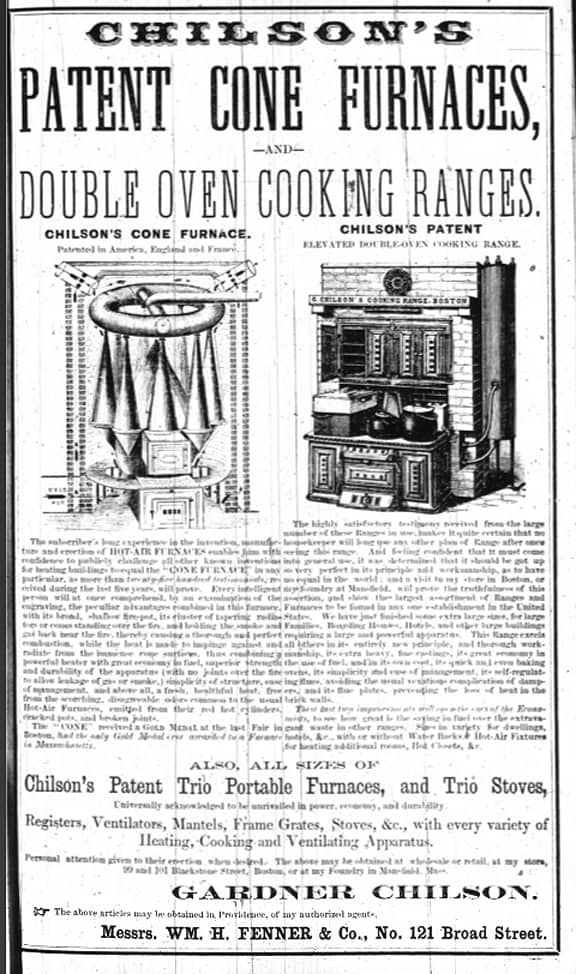

Chilson’s Patent Cone Furnaces and Double Oven Cooking Ranges – Providence Directory Listings – 1861