In from Bill Clements:

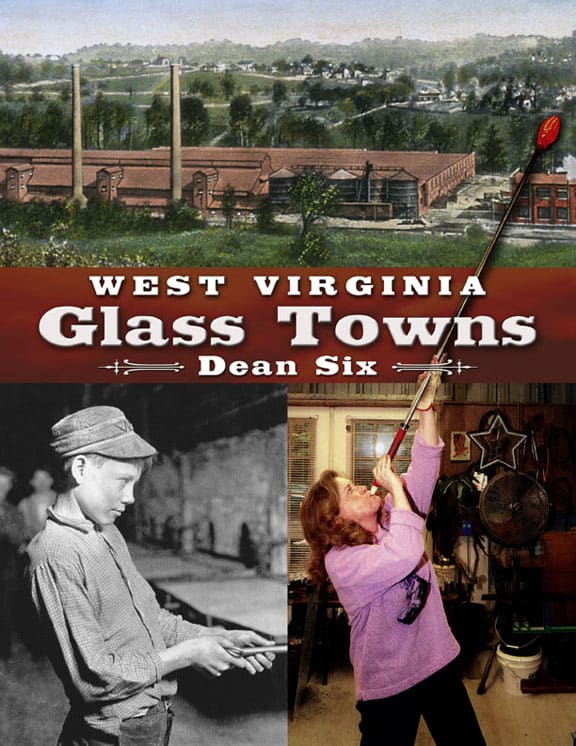

There has never been an effort to take a broad, comprehensive look at West Virginia’s rich heritage of glass production. All that changes with the publication by Quarrier Press of the 20 plus years in the making WEST VIRGINIA GLASS TOWNS. At nearly 200 pages and filled with hundreds of images this is the first ever look at the expansive glass industry in the state.

Over 450 companies and locations have produced hot glass since the first glass was produced in Wellsburg in the second decade of the 19th century. West Virginia Glass Towns provides a town by town list of the glass producing concerns giving dates, product lines and then offers a plethora of photos of glass factories, glass workers, maps, advertisements and much more. The book is a richly textured history using period images to tell the story of what has been a significant industry in the state, an industry that employed tens of thousands of men and women over the nearly two centuries of activity.

The books spans communities from Alum Bridge to Williamstown with significant chapters on know glass communities like Clarksburg, Fairmont, Huntington, Morgantown, Wellsburg, Weston and Wheeling. Also addressed are the numerous factories and glass producers in lesser recognized glass towns such as Cameron, Dunbar, Grafton, Mannington, Parkersburg, Pennsboro and Star City to name but a few.

Fifty-two communities, from larger cities to small towns, are included in the historic and long needed survey of the mountain state glass industry. A brief introductory essay by author Dean Six explains why glass as an industry was prolific in West Virginia and addresses the numbers of factories during the period of phenomenal growth in the early 20th century.

Factories in the state produced flat or window glass, bottles and fruit jars, tableware, glass novelties and a wide range of other glass products, spanning almost the entire spectrum of products made in glass. Factories along the Ohio River began decades before the American Civil War and as of early 2012 there remain 16 hot glass producers active in West Virginia. Many of these are small studio factories producing art glass and one of a kind objects.

This monumental document is the first ever look at the diverse, long lived and major employer in the state.

The book retails for $29.95 and can be found at local bookstores, or through the West Virginia Book Company at 888-982-7472, or www.wvbookco.com

Below is an interview conducted with author Dean Six:

Why is the book important?

This book is important because it tells for the first time the scope and some measure of how really big and important glass has been as a part of the West Virginia story. Nothing before this research even hinted at the size of the glass industry in our state. It is new, exciting and an amazingly big history lesson.

What is the significance of glass making and the glass industry in West Virginia?

Glass has a major role in our state history for the sheer size of the industry. Several larger plants employed 1,000 and 2,000 plus employees. The economic impact over decades was immense. Glass also has given us a bragging point. For decades handmade West Virginia glass has held a place of esteem in decorative, artistic and design circles. We point to Blenko glass in the windows of the National Cathedral or Morgantown Glass on the tables of the Kennedy Whitehouse with pride. In a state where our toils often go unnoticed, to be able to point to a thing we created, a thing of beauty appreciated by others, is a major boost to our collective identity and confidence.

What are some of the more interesting facts from the book?

The sheer volume of hot glass producers in the past 200 years in West Virginia is staggeringly cool. I have documented 459 hot glass makers in West Virginia. When I began this project I started with a list someone else had compiled and it had a little over 100 glass makers. That seemed like a large number, but with each passing year that number grew. Today that 450 plus number yet amazes me. I also find the number of factories in some towns not usually associated with glass to be interesting facts. Parkersburg has been home to 14 glass makers, Mannington has hosted ten. Even locations as far out of the usual glass producing area like Martinsburg and Keyser have had large glass manufacturers. The number and the distribution never cease to intrigue me.

What picture or image is your favorite in the book?

My favorite images are the child labor photos shot around 1908 in several West Virginia towns. Shot to document how young the boys were who worked in glass houses (as young as 8 or 9) and how rough the working conditions were, these timeless photos seem so strong in character. They are my favorites.

What would people with no particular interest or knowledge in glass find of interest in the book?

This is a story about people and history, who cannot find some passing interest in the telling of our own story? The glass is not the focus of the book. There are no actual photos of glass in the entire book. There are parade floats, ball players, Labor Day parades. I think the story is one of how and where we lived, worked and interacted. It is about who we were and are as West Virginians.

How long did it take to write the book?

Over 20 years were spent on chasing the pieces that come together as this book. At one point it was a proposed graduate school topic but academicians were not interested in the topic. Professors, when interested at all, urged me to look at labor issues within the glass industry or to approach it as economics. To me this flattened and dulled the vibrant people, the hot roaring fires and the lure that is glass. I sat in coffee shops in Lumberport and listened to stories of families who had been glass workers, I attended Belgian picnics in Nutter Fort, and I spent hours looking at old newspapers, city directories and courthouse records. It was a statewide snipe hunt at times.

What was the most rewarding thing that happened to you writing the book?

The people. Meeting so many intriguing and vibrant West Virginians. I listened to glass workers, the families of glass workers and literally hundreds of people who wished to relate their experiences and life stories. It is worth noting that many of those I listened to 20 and more years ago are no longer here to see the final product or to elaborate on their stories. I was asking just in the knick of time to catch many of the wonderful tales and reminiscences. I also enjoyed traveling the glass regions of the state. Looking at a parking lot that was pre-civil war glass factories in Ceredo or trying to see a hillside in Wheeling as a 19th century glass factory, where there is now a four lane highway. It was an excellent adventure to try to see what I could identify as being there a century or more ago.

What will this book offer to the average reader?

A sense of the significant role West Virginia played in a major industrial realm. Glass Towns tells and shows a once massive industry that employed thousands but now risks being lost. Here are images of pipe smoking Belgians, massive industrial complexes and small artistic ventures strung across West Virginia. For many of us it will give a new dimension to the towns we grew up in and near. Who would ever guess Belmont, New Cumberland, St. Albans, Elizabeth, Hurricane or Kingwood was once the site of a glass factory?

Why has a book like this not been written before? How did you find all the stuff that is in the book?

The book was not written before because the pieces were so many and so scattered. No one had any sense of how really large this story was, how many towns or people it touched. Had I known it would take 20 years I might have been less willing to undertake it as well. There has never been any attempt to address the glass industry because it is a story with little conflict, unlike the union battles and huge money that has and does encase the history of coal. I cannot say it was not of interest to people, it was and is. Just no one had any idea how to start the research. The advent of computers has aided my ability to do this work as well.

I discovered the thousands of small snippets that make up the big story by traveling back and forth across WV. By asking, then listening to hundreds of people. I did courthouse records room searches, read old copies of local county newspapers, and I followed all the leads that came to me. It took a long time.