Edward Wilder and his Building Bottles

12 February 2012 (R•012614) (R•010919)

![]() This weekend I was cataloging a bottle from Edward Wilder, who was a wholesale druggist in Louisville, Kentucky. I purchased the bottle from John Pastor (Antique Bottle & Glass Collector magazine and American Glass Gallery) at the Yankee Bottle Show in Keene, New Hampshire this past October 2011. Typically, I would pass up a bottle like this except for the fact that this bottle is related to the rather well-known Edward Wilder Stomach Bitters bottle that I own, and I am a bitters collector. The bottle actually has a facsimile of his marble fronted building embossed on the bottle!

This weekend I was cataloging a bottle from Edward Wilder, who was a wholesale druggist in Louisville, Kentucky. I purchased the bottle from John Pastor (Antique Bottle & Glass Collector magazine and American Glass Gallery) at the Yankee Bottle Show in Keene, New Hampshire this past October 2011. Typically, I would pass up a bottle like this except for the fact that this bottle is related to the rather well-known Edward Wilder Stomach Bitters bottle that I own, and I am a bitters collector. The bottle actually has a facsimile of his marble fronted building embossed on the bottle!

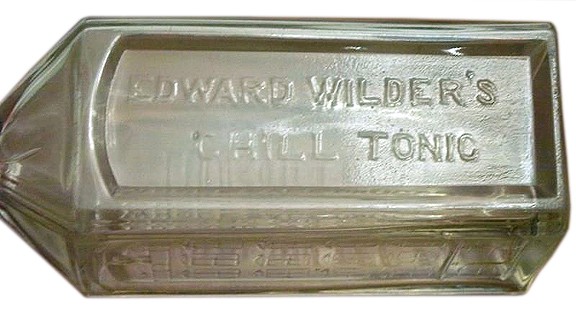

My new bottle was embossed as follows: EDWARD WILDER’S SARSAPARILLA & POTASH (Motif of Building), EDWARD WILDER & CO., WHOLESALE DRUGGISTS, LOUISVILLE, KY.

This is a smaller version (8 3/4″ x 2 1/4″ square) of the famous clear or colorless bitters bottle of the same (almost) shape and form. The glass is heavy and the bottle is highly detailed with the strong 5-story building embossing, which is not typical of the bitters bottle. This bottle also does not have the ‘hob-nailed’ corner bumps as the bitters bottle (see pictures further below). Wilder bottles typically come in three sizes from 10 1/2″ to 4 3/4″ as shown below from Frank Wicker’s Bottle Pickers web site.

EDWARD WILDER’S SARSAPARILLA & POTASH

Here is my new bottle purchased at the Yankee Bottle Show in Keene, New Hampshire.

EDWARD WILDER’S STOMACH BITTERS

Now to my bitters bottle from Edward Wilder that was one of my first bottle purchases back in October 2002 from James Chebalo on eBay. Jimmy has since passed on, sad to say.

The Carlyn Ring and W.C. Ham listing in Bitters Bottles is as follows:

W 116 Edward Wilder’s Stomach Bitters

EDW WILDER’S / STOMACH BITTERS // motif five story house // EDW WILDER & CO / WHOLESALE DRUGGISTS / LOUISVILLE. KY // sp // // s // sp // PATENTED // sp // sp //10 1/2 x 2 3/4 (7)

Square, Clear, LTC, Tooled lip, 4 sp, Very Scarce

16 bumps on each corner “hob nailed”. Bottle usually weekly embossed. Strip under the mortar has 5 circles with vertical lines between the circles. Mortar and pestle over window with arabesque on each side.

Trade Mark No. 21263 Stomach Bitters and Compound of Sarsaparilla and Potash. Renz and Henry, Louisville, Ky. Filed April 29, 1892. Registered June 7, 1892.

Edward Wilder’s Sarsaparilla and Potash bottle is the same as the bitters bottle, only difference is the wording STOMACH BITTERS. Bottle is actually smaller.

Tr-Weekly Advocate (Baton Rouge, La.) February 10, 1869

Resembles Dr. DeGurley’s Bitters

Propriety Stamps: 1 cent green, 4 cent black blue, 4 cent red, Edward Wilder, Sole proprietor.

W116.1 and W116.2 are variants with deviations primarily in building architural detail.

Bitters collector Brian Shultis contacted me after a Facebook post on PRG today and stated that there are several different mold variants of the Edward Wilder’s Stomach Bitters. Some have PATENT on the shoulder. There is also an extremely rare Edward Wilders Bourbon Bitters and a Edward Wilders Compound of Wild Cherry bottle and a smaller Mother’s Worm Syrup. I have always liked the Wilders bottles. Very cool!”

EDWARD WILDER’S BOURBON BITTERS

Image needed.

W 116.5 Edward Wilder’s Bourbon Bitters

EDW WILDER’S / BOURBON BITTERS // motif five story house // EDW WILDER & CO / WHOLESALE DRUGGISTS / LOUISVILLE. KY // sp // // s // sp // PATENTED // sp // sp //10 1/4 x 2 3/4 (7)

Square, Clear, LTC, Applied mouth, 4 sp, Extremely rare

16 bumps on each corner “hob nailed”.

EDWARD WILDER’S CHILL TONIC

Photos courtesy Brian Shultis

EDWARD WILDER’S COMPOUND EXTRACT OF WILD CHERRY

Image needed.

MOTHERS WORM SYRUP

WILDER’S STOMACH BITTERS TRADE CARDS

The following advertising trade cards are from the Joe Gourd collection.

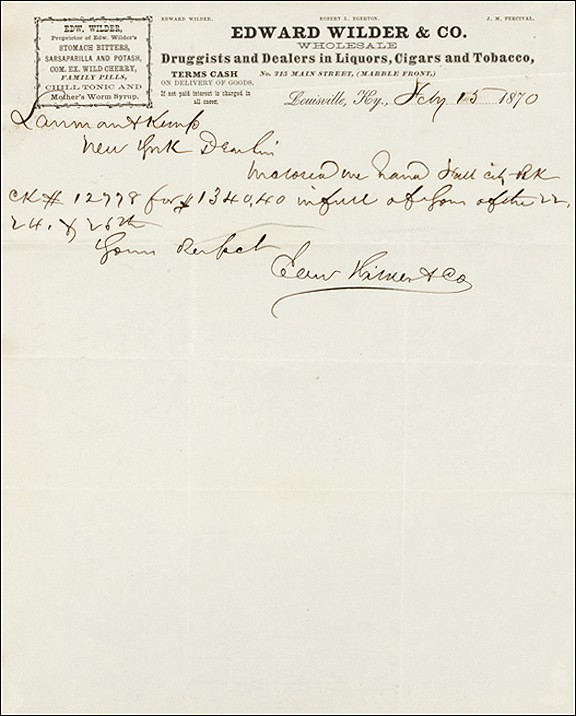

EDWARD WILDER & COMPANY LETTERHEAD

Here is an Edward Wilder & Co. original July 15, 1870 letterhead receipt from my collection. Notice the partner names listed at the top and their brands listed at the upper left.

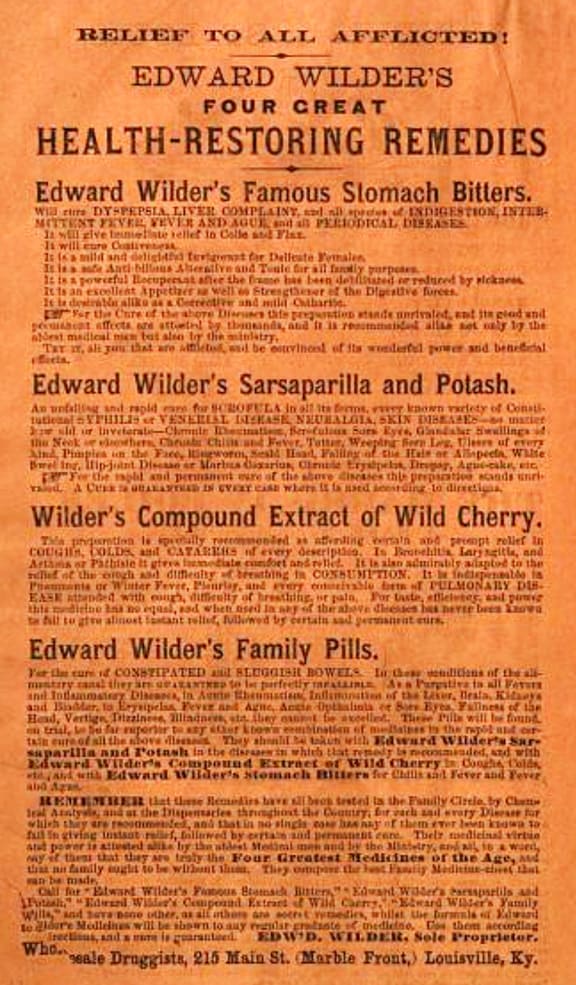

EDWARD WILDER’S ADVERTISING

Edward Wilder’s Four Great Health Restoring Remedies – Debow’s Review: Agricultural, Commercial, Industrial Progress and Resources – J. D. B. DeBow, 1867

Use Edward Wilder’s Stomach Bitters, Edward Wilder, Sole Proprietor, No. 215 Main Street, Marble Front, Louisville, Kentucky – The Louisville Daily Courier, Thursday, October 18, 1866

PROPRIETARY STAMPS

Three Generations of Edward Wilder

Leading up to Edward Wilder’s Stomach Bitters, we see that Edward Wilder (grandfather) was the first of three generations of Edward Wilders. He resided at Bird’s Creek, Charles County, Maryland. He died in 1779, leaving only one son, who was also named Edward Wilder. The second Edward was born on the December 10, 1779, a few weeks after the death of his father. Edward served with much distinction as captain of a company in Colonel Thomas Neill’s regiment of cavalry in the State of Maryland during the War of 1812.

Wilder married Susan Key Egerton (1795–1879), on the February 14, 1811. At the time of their marriage, he had been a clerk for her father, and was engaged to be married to Susan at the time of her father’s death. They were married soon after, and he moved into the business of his father-in-law, who was a farmer and merchant at Chaptico, a small town in St. Mary’s County, Maryland, which is southwest of Washington, D.C.

Chaptico lies on Chaptico Run, which forms a bay as it enters the Wicomico River and eventually the Chesapeake Bay. Chaptico may be Algonquian for “big-broad-river-it-is” and related to the friendly Chaptico tribe visited by Governor Charles Calvert in 1663. The town was a shipping point until the Wicomico River silted up in the 18th century. It was damaged by the British in 1813, during the War of 1812. Some of its prominent citizens were pro-Southern and jailed during the Civil War.

Wilder continued his business until his father’s death on the January 7, 1828. The elder Wilder left a widow with five children; three sons and two daughters, Margarette, born February 17, 1813; Mary, born April 14, 1815; James Bennett, born July 12, 1817; Oscar, born June 4, 1819; and Edward, born December 31, 1825, this being the third Edward Wilder of the family. This is the Edward Wilder of Wilder’s Stomach Bitters from Louisville, Kentucky.

Edward Wilder (the father) was described as a tall, spare man who was industrious and enterprising, and was highly respected in the community where he resided. Wilder and his wife were both Episcopalians by birth and Wilder, though not a communicant, was exceedingly fond of taking his family to church every Sunday. They continued, after the death of Wilder, to reside in St. Mary’s County, Maryland, until December, 1830. The spirit of emigration to Kentucky and Missouri began to run pretty high, and Mrs. Wilder, believing it would be best for her young and growing family, decided to break herself loose from the friends and relations by which she was surrounded and seek a new home in the wild Western world, and on December 18, 1830, they landed at Louisville, Kentucky.

Soon after their arrival in Louisville, James Bennett Wilder engaged as a clerk in a local wholesale drug house. The two other sons, Oscar and Edward, were sent off to school. In 1834, Oscar left school and engaged his services to the same firm with whom James Bennett was employed. On the October 15, 1838, they both purchased the business in which they were employed and commenced for themselves as J. B. Wilder & Company, first located on the east side of 4th, between Main and Market Streets. In 1853, the firm became J.B. Wilder & Bro., the brother being Oscar. This is about the time Edward Wilder joined as a clerk. Unfortunately, Oscar died in May 1854 after an accident involving a fall through a trap door. After that event, Edward became the Brother partner in the firm. In July 1858, James Bennett and Edward Wilder dissolved the partnership and Edward kept the druggist business.

It would take James Bennett time to rebound and he opened his own competing drug business, J. B. Wilder & Co., at 181 West Main between 5th and 6th. His two partners were Thomas O’Mara and Graham Wilder from 1866 to 1871. O’mara actually had his own bitters called O’mara’s Fenian Bitters (O 63). James Bennett Wilder was very successful and considered a prominent area businessman with his drug firm. He was also a director of both the Louisville & Nashville Railroad and Bank of Louisville. James Bennett also rebuilt and lived in the historically significant Bashford Manor Estate in Louisville which is a three-story brick mansion designed in the French Renaissance style with a mansard roof and fifteen rooms. The home was built in 1871-72 and was named after both Wilders ancestral home in Maryland and the English home of his ancestor, Lord Baltimore.

Interesting to note, at this same time, John Bull, another medicine man, moved to Louisville and worked at Hyer’s and Butler’s drugstore. In 1837, he opened his own store, which failed within two years. Bull then joined the wholesale drug firm of James B. and Edward Wilder as a prescription clerk, who also marketed a line of proprietary remedies. Bull is listed as an employee of J.B. Wilder Co. in Collins’ 1843 Louisville Directory, but by 1845 he was in partnership with Robert Bower manufacturing a “tonic syrup”. Bower withdrew from the business by 1847. With new financing, possibly from Edward Wilder, Bull began to market a sarsaparilla mixture (ca. 1850) – first in Kentucky and then in other states.

Read: Dr. John Bull and Louisville at that time

Edwards renamed the firm, Edward Wilder & Company, Druggists, as noted above, and remained at 215 West Main, between 6th and 7th Streets. This is where he promoted his marble-faced building. The building was eye-catching with a gothic front and moulding, and the only one in the West according to advertising. The stone was procured in Indiana and looked equally as well as the much-admired Boston granite. The Wilder Company graphics adorned the front in beautiful block letters and a mortar and pestle completed the crown. There was also a beautiful and immense sky light used for dramatic effect. The establishment was 191 feet in length, and 24 feet wide and had a cellar and five stories. Here they sold large quantities of drugs, chemicals, paints, oils, and dye-stuffs that were replenished on a daily basis. His partners were Robert L. Egerton, and J. Murray Percival. Egerton should sound familiar to Kentucky bottle collectors as his R.L. Egerton Bitters (pictured below) is listed in the Top 25 Kentucky Bitters Bottles list.

Edw. Wilder and Co. were listed from about 1866 to 1871 as the proprietors of Edw. Wilder’s Stomach Bitters, Sarsaparilla and Potash, Compound Extract of Wild Cherry, Family Pills, Chill Tonic and Mothers Worm Syrup. He spent large sums of money advertising his brands and was recorded as spending $40,000 to advertise his stomach bitters alone.

If you are wondering why two Wilder brothers would each have wholesale and retail druggist concerns within the same area of downtown Louisville, it was not for consumer convenience. These two competed in the market and in the courts. The stories in this arena are fascinating. An example is noted below regarding James Bennett Wilder piggy-backing on his younger brother Edwards successful Edward Wilder’s Stomach Bitters. Using his position as a director for the L & N Railroad, James Bennett set out to adorn every car on the main line and on every branch of the Louisville and Nashville railroad with unpaid for placards advertising Edward Wilder’s Stomach Bitters. As you will see below, he created facsimile bottles and labels, and filled them with his version of the bitters. He then sold them to customers under the guise of his brothers bitters and kept all the profits! I can not find any surviving examples of this bottle, though it was apparently not as ornate.

J. B. Wilder & Co. v. Edwd. Wilder

Trade-marks and Trade-names—Unfair Competition.

One who, by the style of the bottle used and the label thereon, undertakes to put a medicine on the market by deceiving the public into the belief that they are buying medicine made and sold by another who by much advertising and expenditure of money created a public demand therefor, is guilty of unfair competition.

Trade-marks and Trade-names—Unfair Competition—Defense.

One who is seeking to profit by unfair competition, will not be permitted to profit from his own wrong by alleging fraud on the part of the other party, where there is no evidence of fraud on the part of the latter unless it exists in the extravagant statements of the latter as to the curative qualities of his medicine.

APPEAL FROM LOUISVILLE CHANCERY COURT.

February 6, 1873.

Opinion By Judge Pryor:

After a careful examination of all the evidence bearing upon the issues involved in this case, we have no doubt but what the object of J. B. Wilder’s visit to Pittsburg in August, 1867, was to have moulded and made for the firm of J. B. Wilder & Co. bottles for their stomach bitters as nearly similar as possible with the bottles used by Edward Wilder, without having them in every respect identical. The appearance of the bottles connected with the evidence on that subject shows a studied effort to have appellants’ bottles and the labels thereon so strikingly similar to those used by the appellee as to deceive and mislead the public. The appellee had expended large sums of money in advertising and making public the virtues of his medicine and seems to have succeeded in inspiring the public with the same confidence in its curative qualities that he himself had. The popularity of his medicine was increasing constantly, owing to his untiring energy in retailing it all over the country by his traveling agents and his lavish expenditure of money for that purpose. The appellants, so far as appears from this record, had never advertised their medicine in a single paper, and were evidently looking to the resemblance between their bottles and medicine and those of Edward Wilder as the only means of its successful introduc

Opinion of the Court.

An ordinary observer might easily be deceived on account of the striking resemblance of the bottles of each and the labels upon them, and in our opinion the evidence is so conclusive on this branch of the case as renders it useless to discuss it. The appellants insist, however, that the manufacture and sale of the medicine by the appellee is a fraud and cheat on the public and therefore a court of equity should deny him any relief, and if an injunction should even be proper, the chancellor has gone too far in the restraint he has placed upon them. There is nothing in the case showing that the medicine possesses any injurious qualities, but on the contrary it appears that it is composed of the best and purest drugs. It is true, men of science in the medical profession indicate by their statements that it is worthless and must necessarily fail to possess the virtues attached to it by the appellee; still if the people are disposed to buy it, upon the extravagant laudation of its medicinal and curing qualities we are inclined to think they should be permitted to exercise this right. The appellee may be acting in good faith when he publicly announces his belief in the many virtues of his medicine and if the public are willing to be humbugged the chancellor will not undertake to prevent it.

The medicine itself is harmless and it does not appear that the public or any individual has been injured by its use. If it was composed of poisonous compounds or of such ingredients as would likely injure those using it, there might be some reason for refusing the relief sought. The appellants, however, not satisfied with using the trade mark of the appellee, a fact mutually admitted by them in their answer, are also conceding for the purposes of the defense a knowledge on their part that the medicine is valueless and an imposition on the public; “that it lives by its success in misleading the public in buying it for virtues it assumes, but has not, when it appears from the proof that they are making the same medicine out of inferior compounds and relying upon the reputation of appellee’s medicine, acquired at an expenditure of many thousand dollars, for its sale. There is no evidence of any deception or fraud practiced by the appellee unless it exists in the extravagant statements of the curative qualities of his bitters and, although one must be very credulous to believe in the representation as to the wonderful and many virtues of the medicine, still this court will not presume intentional wrong on the part of the appellee in the Opinion of the Court absencent of all proof of injury resulting from its use.

His own confidence in its medicinal qualities is evidence to some extent, at least by his expenditure of thirty-five thousand dollars with no other means of recompense than his success in selling it. Such medicines are only valuable to the extent in which they are appreciated by the public and the appellee, having made his experiment a success by much labor and a large outlay of his means, the appellants should not be allowed to reap the benefit resulting from it, nor will they be allowed under the charge of fraud and deception against the appellee to avoid their own wrong. The attitude in which they place themselves by their defense in this case is not calculated to bring them into favor with the chancellor and his restraining order will not be interfered with by the judgment of this court. The judgment is affirmed.

Barrett, Robert, Pirtle & Caruth, for appellant.

Jos. Speed, Caldwell, W. A. Bullitt, Thos. Speed, for appellee.

There is also another bitters bottle that is embossed with a building and that is the Dr. DeGurley’s Herb Bitters that was manufactured in Baltimore.

Edward Wilder would die on March 25, 1890. His bitters sold all the way to 1884, which is pretty amazing.

[Post assistance from The American Revenuer, The Case of Wilder V. Wilder and the Book of the Wilders: a further contribution to the history of the Wilders, from 1497, in England, to the immigration of Martha, a widow, and her family to Massachusetts bay, in 1638, and so, through her family down to 1875: with a genealogical table among other sources]

James Bennett Wilder | J. B. Wilder & Co. Advertising

J.B. Wilder & Co.,Importers and Jobbers of Drugs, 181 Main, bet. 5th and 6th – Louisville, Kentucky, City Directory, 1866