Some Information on New England and Midwestern Pitkin Flasks

16 February 2012 *Post amended 21 February 2012 with Dana Charlton-Zarro information and Dave Maryo image. * Post amended 09 April 2012 with additional Pitkin Ruins image of archway.

The Honorable William Pitkin, served on the Connecticut General Assembly – photo provided by Rick Ciralli

![]() Jeff Noordsy (visit Jeff and Holly Noordsy online) posted a beautiful picture of three Pitkin flasks (pictured above) that got me wondering about the history and differences between the molds and glass works that made them. I’ve compiled some information and support pictures. This is a great way for me to get a broader knowledge on this topic for the FOHBC Virtual Museum of American Historical Bottles and Glass project. I have got to be able to at least swim with the big fish that collect and research this topic.

Jeff Noordsy (visit Jeff and Holly Noordsy online) posted a beautiful picture of three Pitkin flasks (pictured above) that got me wondering about the history and differences between the molds and glass works that made them. I’ve compiled some information and support pictures. This is a great way for me to get a broader knowledge on this topic for the FOHBC Virtual Museum of American Historical Bottles and Glass project. I have got to be able to at least swim with the big fish that collect and research this topic.

Pitkin Flask: Small bottle of green glass in an ovoid and flattened shape made by the “Half-Post Method”. In this method a second pattern molded gather of glass is put over an optically blown flask. The first layer molded flask is turned one way and the second layer is turned the opposite way giving an interesting pattern. Then the flask is expanded to the ovoid and flattened shape.

[PRG] Follow-up correction to process in which Pitkin Flasks were formed by Pitkin authority Dana Charlton-Zarro. PRG thanks Dana.

Ferdinand, thank you for your very interesting article on Pitkin flasks. However, may I respectfully correct a statement made, and provide you and your readers with the manner in which these flasks were formed: after the first gather of glass was semi-formed into the shape of a bottle, the still-pliable gather was dipped into the molten materials again, this time up to the shoulder of what was to become the flask, creatng the “German half-post” or “half-post” — and only then, after it had both layers of glass, was it was dipped into a pattern mold, removed, swirled, and reinserted into that mold (or another if a different rib count was desired) and given the second rib impression, then expanded.

That is, both patterns were impressed into the molten glass after both layers of glass had formed the flask. It was usually the same pattern mold (same number of ribs), and it was swirled first. The second insertion into the pattern mold was used for vertical ribs so as not to obliterate the swirls. (That is what makes the cross-swirled patterns on the few known so much of a mystery even to those of us who have studied Pitkins for many years.)

If it were done as your article stated, one pattern per layer of glass, then the second layer of glass would fill in the spaces in-between the ribs of the first layer, but this is not so on the flasks & inkwells we’ve come to know (and some of us love) as Pitkin-types.

Pitkins have been studied for many years, and are a difficult form for the unitiated. In years gone by, for example, the people used to think that the “half -post” was an “inserted neck”.

Insofar as the number of ribs on Midwestern Pitkin-types (16), and New England Pitkin-types (36), those are the typical count, but many examples have been discovered with a different number, or even a combination of molds used. One of my New England flasks has a 38 rib swirl pattern together with 36 ribs. Pitkin-type flasks were also blown in the “Mid-Atlantic” — New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and probably New York. The number of ribs on those examples are different still.

To this collector, all of the are gems, and I thank you for your article and the opportunity to clarify the method used to make them.

Dana Charlton-Zarro

Originally these flasks were made in The Pitkin Glass Works in Manchester, CT (1788-1830). They were made later in other parts of New England and in the Midwest (e. g. Zanesville, Ohio 1810-1830). Today they are classified as being New England Pitkins or Midwestern Pitkins. You can usually tell the difference by counting the ribs. The New England is 36 ribs and Midwestern 16 ribs. In addition to various shades of green they can be found in amber, blue (rare), amethyst (rare) and colorless glass. The flask came in two main sizes half pint and pint, used as a pocket flask for whiskey.

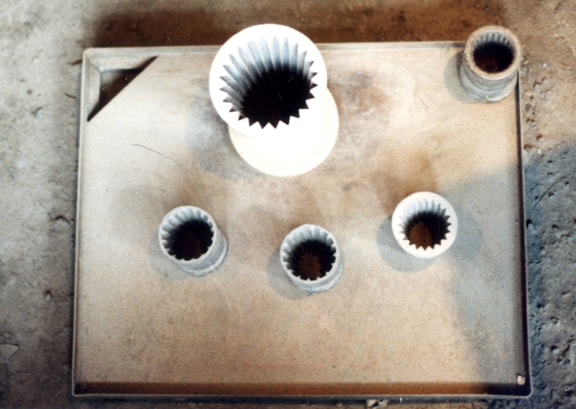

Photo of original dip molds used at some northern Ohio glass factories. The photo was taken at the Hale Farm and Village in the early 1980s – courtesy Dave Maryo

The Pitkin Glassworks 1783-1830

[from the Manchestor Historical Society] In 1783, Connecticut’s General Assembly granted Captain Richard Pitkin and his sons a 25-year monopoly on manufacturing glass, as recompense for their providing gun powder, at a loss, to the Connecticut militia, 1775-1781. The Pitkin Glass Works, the first successful glass factory in Connecticut, was built in Manchester (then the Orford Parish of East Hartford) on the Pitkin farm, now on the corner of Putnam and Parker Streets. Remaining in operation until about 1830, the factory produced demijohns for the West Indian trade, and bottles, flasks, inkwells and other small items, mostly in shades of green. These were considered to be the best color and design in the country. Rare today, Pitkin flasks have brought tens of thousands of dollars at auctions.

It is not known why the factory was closed down. Perhaps it was because of the cost of transporting sand from New Jersey, or because the firewood supply was decreasing with the growth of farming in the area. There may have been poor management, or increasing competition from other factories once the monopoly expired. Gradually, the massive stone building fell into disrepair.

In 1928, Mr. And Mrs. Fred W. Pitkin and others of the Horace Pitkin family quit-claimed the property to the Orford Parish Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Finding the cost of maintenance a burden, a suggestion was made in 1977 that it be sold for commercial purposes.

A group of interested citizens, led by Mr. Edson Bailey, protested this possibility, and formed a committee to preserve this historic site for the community.

Pitkin Glass Works Inc. (the Corporation) was organized, with executive officers, and five representatives from the Orford Parish Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution; five representatives from the Manchester Historical Society, Inc.; and five representatives from the citizenry at large. Papers were filed for incorporation, and by-laws were drawn up. The site was approved for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places.

Since then, the Corporation has overseen the landscaping of the area, and installed a flagpole with a flag that has flown over our national capitol. The monumental stone ruins have been stabilized by repointing the stonework and replacing the wood lintels.

In the 1980s, students from Central Connecticut State University made a preliminary archaeological dig, but only shards of glass and pottery were found. In recent years, several archaeological digs have been carried out by middle school, high school and university students under the direction of the state archaeologist. Numerous pieces of bottles, flasks and inkwells have been discovered and cataloged. The fragments have confirmed the characteristics of the products made here.

All the funds to support the work of the Corporation have been raised by the generosity of private benefactors, or through the sale of replicas of a Pitkin flask and an inkwell, and pendants made from fragments of glass. An illustrated hard-cover book by Dr. William E. Buckley, “A History of the Pitkin Glass Works,” has also been published.

The Corporation remains active, carrying out its mandate to maintain and preserve this part of our heritage for future generations.

Ohio and Midwestern Glass

[By George S. McKearin] (This article originally appeared in American Collector magazine, a publication which ran from 1933-1948 and served antique collectors and dealers.)

This article on Ohio and Midwestern glasshouses in the early 19th century focuses on techniques, designs, patterns, and types of wares made, as well as including a list of glasshouse towns and glassmakers. It originally appeared in the November 1940 issue of American Collector magazine, a publication which ran from 1933-1948 and served antique collectors and dealers.

Among collectors, the blown glass which was made at the early glasshouses of Ohio and the Midwestern district has long been highly regarded. The craftsmen working there seem not only to have followed the Stiegel technique but to have developed and even created forms, colors, and elaboration of pattern-molded designs that were distinctly American. This is well illustrated in the beautiful swirl design, so frequently with a delicate feathery effect, produced from part-sized, vertically ribbed molds (Illustrations I and V).

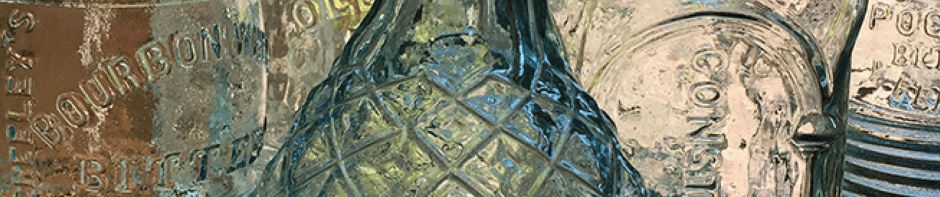

New England & Midwestern “Pitkin” flasks produced between the 1790s and 1830s – photo High Desert Historic Bottle Website –

As rare as hen’s teeth, this 5 1/4″ high amber Ohio flask has a pattern known to collectors as “popcorn.” – Ian Simonds – Early American Glass

Midwestern Pitkin Style Flask – 30 rib broken swirl pattern molded flask. Exceptional “popcorn” pattern – photo BottleNut.com

Ferdinand, thank you for your very interesting article on Pitkin flasks. However, may I respectfully correct a statement made, and provide you and your readers with the manner in which these flasks were formed: after the first gather of glass was semi-formed into the shape of a bottle, the still-pliable gather was dipped into the molten materials again, this time up to the shoulder of what was to become the flask, creatng the “German half-post” or “half-post” — and only then, after it had both layers of glass, was it was dipped into a pattern mold, removed, swirled, and reinserted into that mold (or another if a different rib count was desired) and given the second rib impression, then expanded.

That is, both patterns were impressed into the molten glass after both layers of glass had formed the flask. It was usually the same pattern mold (same number of ribs), and it was swirled first. The second insertion into the pattern mold was used for vertical ribs so as not to obliterate the swirls. (That is what makes the cross-swirled patterns on the few known so much of a mystery even to those of us who have studied Pitkins for many years.)

If it were done as your article stated, one pattern per layer of glass, then the second layer of glass would fill in the spaces in-between the ribs of the first layer, but this is not so on the flasks & inkwells we’ve come to know (and some of us love) as Pitkin-types.

Pitkins have been studied for many years, and are a difficult form for the unitiated. In years gone by, for example, the people used to think that the “half -post” was an “inserted neck”.

Insofar as the number of ribs on Midwestern Pitkin-types (16), and New England Pitkin-types (36), those are the typical count, but many examples have been discovered with a different number, or even a combination of molds used. One of my New England flasks has a 38 rib swirl pattern together with 36 ribs. Pitkin-type flasks were also blown in the “Mid-Atlantic” — New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and probably New York. The number of ribs on those examples are different still.

To this collector, all of the are gems, and I thank you for your article and the opportunity to clarify the method used to make them.

Dana Charlton-Zarro

Great comment Dana….I will asterisk and/or modify the comment in the article and make sure readers see your comment here below. One thing I have found out for sure, and that is, that there is conflicting information available from seemingly reliable sources. It is only by posting that I get comments from experts in areas such as yourself with Pitkins that help to set the record straight. Of course new information is always surfacing too. Again thanks for your excellent response. F

Thank you very much Ferdinand. I’d be interested in having a conversation with whoever gave you the information about the pattern molding on the Pitkins. Senior collectors & students of Pitkin Glass Works, and other authorities such as Helen McKearin, Ken Wilson, and others believe that the half post (second layer of glass) had already been applied before the first dip into the pattern mold. I can understand, though, the misunderstanding, because it was such a skill to form a broken-pattern molded flask that people wonder how it was possible. In 26 years of collecting and studying Pitkins, this is the first time I have heard the theory of one layer of glass, one pattern; second layer of glass, second pattern. I’m glad you brought it up, bringing that theory into open discussion.