The objects were produced by blowing molten glass into a mold, thereby causing the glass to assume the shape and pattern design of the mold.

Early American Blown Three Mold Decanters

30 April 2012 (R•031414)

An area of high interest to me is early American blown three mold glass and in particular decanters. Elizabeth and I typically see decanter pieces at the mid Atlantic and New England shows such as Baltimore, Heckler in CT and Keene, NH. I really like the geometric pattern and beauty of these pieces since they seem so different from the Bitters bottles I collect. With examples periodically appearing in auctions and facebook on the bottle group sites such as Bottle Collectors and Early American Glass, I thought it was high time that I dig a little further into this area. I also realize this will be an important part of the FOHBC Virtual Museum of Historical Bottles and Glass.

I have compiled some pictures and information from Wikipedia which seems like a good place to start. Information is limited online which is surprising but I did find a nice article by New England collector Michael George. Read More: Glassmaking in “early” New Hampshire by Michael George

Early American molded glass refers to functional and decorative objects, such as bottles and dishware, that were manufactured in the United States in the 19th century. The objects were produced by blowing molten glass into a mold, thereby causing the glass to assume the shape and pattern design of the mold.

Common blown molded tableware items bearing designs include salt dishes, sugar bowls, creamers, celery stands, decanters, and drinking glasses. Household items, other than dishware, made using the three-mold method include inkwells, oil lamps, birdcage fountains, hats, medicine and perfume bottles, and witch balls. Whiskey flasks bearing unique designs were made in two part molds. Undecorated bottles used as containers for a variety of liquids were blown into square molds to give them corners so they could be packed into compartments of wooden cases.

After the War of 1812, American glass manufacturers began using molds as an inexpensive way to produce glassware similar in appearance to the very costly cut glass that was imported from Waterford, Ireland. A dearth of skilled glassblowers may have also led to the increased use of molds. Blown molded glass was popular for about twenty years before it was superseded by pressed glass.

The process of blowing molten glass into a mold made of clay is known to have been employed in Syrian workshops as early as the 4th century BC. Romans adopted the technique in the 1st century CE. Molds used in 19th century European and American glass factories were cast in iron or bronze. They were made by professional mold manufacturers in many large United States cities and were universally available.

Although no intact molds have been found, fragments of molds have been excavated at glass manufacturing sites in Sandwich, Massachusetts and Kent and Mantua, Ohio.

The mold, which was placed on the floor or below floor level, was not three molds, but one mold in three parts. It was made of hinged sections that could be opened and closed by means of a foot or hand operated treadle. One of the vertical walls of the mold was permanently fastened to the base and the other walls were attached to it by removable pins. Designs were cut into the inside walls of all mold parts. Some molds impressed a pattern on the object and base, while others omitted the base. Most molds were in three parts, but could also be constructed of two or four parts. Regardless of the number of parts of a mold, all objects produced in a mold are called three-mold glass.

The process of molding was just the initial step in the manufacture of three-mold glass. After removal from the mold, the glass was expanded by means of additional blowing. The object was then cracked off at the rim and hand finished by grinding and polishing. Pitcher rims, decanter necks and bases all required hand work. In New England, pieces were often finished with threaded lips. Handles were also added after removal from the mold. Lamps, candlesticks and vases were pressed in separate parts and fused together while still hot. Finished pieces were fire polished by reheating in the furnace, which softened the pattern and gave the piece a diffuse brilliance.

Between 1820 and 1840, one hundred glass factories are known to have been in operation in the U.S. It is known from descriptions in advertisements and invoices that the Boston and Sandwich Glass Company and the New England Glass Company were major producers of blown three-mold glass. Most colorless glass was made by the New England Glass Company in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Also producing three-mold glass in New England was the Boston Crown Glass Manufactory, as well as the Quincy Glass Works in Massachusetts, which made snuff bottles molded to a square form.

Three-piece molds were used from 1815 to 1835 in midwestern houses, most notably in Ohio. Marlboro Street Factory in Keene, NH manufactured dark green and amber bottle glass and was known for the manufacture of inkwells. In New York and New Jersey, famous glass manufacturers of blown three-mold glass include the Mount Vernon Glass Company, Brooklyn Flint Glass Works, and Jersey City Glassworks. The Coventry, CT Glass Company was also a manufacturer of three-mold items. It is believed that glass factories in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and Baltimore also produced three-mold glassware, but since excavation is not possible, no proof exists. Some foreign molded three-part glass manufactured in England, Ireland (two part molds) and France (three part molds) in the early 19th century, is sometimes mistaken for American glass.

Colors of blown three-mold glass are relatively rare, however, some objects in deep gray-blue, sapphire blue, olive green, yellow-green, citron, aquamarine and amethyst-purple have survived. Items made of colorless glass and green bottle glass are most commonly seen.

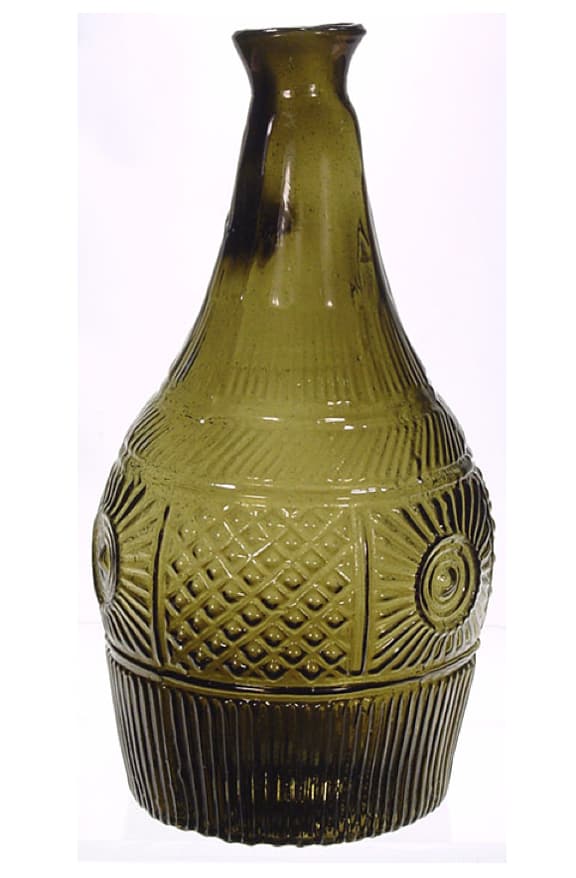

The three main categories of three-mold glass patterns are Geometric, Arch and Baroque. Diamond patterning, also known as diamond diapering or diamond quilting, is the most common Geometric design found on molded glass. Other common designs include ribbed and popcorn. Items bearing Geometric designs are the most numerous and include tableware, such as decanters, stoppers, cruets, casters, condiment sets, pitchers, punch bowls, pans, dishes, preserve dishes, mugs, tumblers, wine glasses, celery glasses and salts, and doll dishes. Also in the Geometric category is ribbing, which could be imprinted on the object vertically, horizontally, diagonally or in a swirled pattern. Ribs can be narrow or wide, differently spaced, rounded, flat or inverted. Arch, the most rare of the three designs, uses a series of Gothic (pointed) or Roman (rounded) arches. Sometimes both types of arches appear. Baroque patterning includes Shell (rocaille) ornaments with broad, rounded, vertical ribbing and often combined with design of a band of palmettes or trefoils. Other Baroque designs include stars in circles, rosettes, thick chains (guilloches), hearts, a horn of plenty, pinwheels, and fluid drapery.

Blown three mold decanter, (McK# GII-3), deep olive green, cylindrical, pontil scar, half-pint, applied sloping collar with ring. Blown at the Keene Marlboro Street Glass House, Keene, NH, 1820-1840, extremely rare. This truly exceptional blown three mold decanter is one of four known examples and one of only two in private hands. The other examples can be found in the Toledo Museum of Art, Winterthur and in a 40 year New England Collection. For those who have collected since the early 90s you may remember that this example was unearthed on Cape Cod and sold in Heckler Auction #5 for $9900 – Jeff and Holly Noordsy

Pair of colored blown three mold! This is the Quart and 1/2 Pint sized GII-3. As far as I know, a pint does not exist – Michael George

Quart Flint glass decanter with the word SCOTCH embossed inside an area that is encircled by snakes. Decanter is referenced in several places in McKearins book as the GIV-7 pattern. It dates from the 1830’s, and was noted as produced by the Boston & Sandwich Glass Company in Massachusetts. See comment at bottom of post.

Another Great pair of Blown Three Mold…the GIII-2 in the Pint and Quart size, attributed to the Mt. Vernon factory, 1820s. This historic glass has beauty and rarity! – Michael George

Pair of three mold blown decanters with original stoppers, (McK# GI-29), deep cobalt blue, pontil scars, half-pints, tooled and flared mouths, mint. American, probably blown at the Sandwich Glass Works, Sandwich, MA, 1820-1840.

I dedicated this post to Michael George awhile ago. He really did inspire me (along with Mark Vuono) and I assembled a trio of Keene GIII-16’s in colors. The darker green one has exceptional mold definition….Rick Ciralli

Blown three mold decanter, (McK# GI-29), pale yellow green, cylindrical, pontil scar, quart, as found with a 6″ long crack. Blown at the Mount Vernon Glass Works, Vernon, New York, 1820-1840, very rare.

Blown, three mold decanter, GIII-16, yellowish olive green. Keene Marlboro Street Glassworks, 1820-1840 – GreatAntiqueBottles.com

Pair of three mold blown decanters with original stoppers, (McK# GIII-26), clear with a moonstone tint, cylindrical, pontil scars, quarts, flared mouths, about mint. American, 1820-1840, very scarce – Jeff and Holly Noordsy

Blown three mold decanter, (McK# GIII-2 Type 1), clear olive green, cylindrical, pontil scar, quart, flared mouth, Blown at the Mount Vernon Glass Works, Vernon, NY, 1820-1840, rare.

Hi, I stumbled across your article on this decanter described below:

“Quart Flint glass decanter with the word SCOTCH embossed inside an area that is encircled by snakes. Decanter is referenced in several places in

McKearins book as the GIV-7 pattern. It dates from the 1830s, and was noted as produced by the Boston & Sandwich Glass Company in Massachusetts.”

I’m not certain, but it might have been Ian Simmonds, that told me that decanters with the word “SCOTCH” on them in this pattern were reproductions.

The only thing that I can say on this, myself, is that in the decanter listings in McKearins, there is not one reference to any of the Blown Three mold

decanters ever being blown with the word “SCOTCH” on them. Please look through McKearins listings for yourself, to verify and then correct your

article, if I am, in fact, correct.

Andrew E. Ames