C O C A I N E

“Nobody saves America by sniffing cocaine. Jiggling your knees blankeyed in the rain, when it snows in your nose you catch cold in your brain.” – Allen Ginsberg

The Lure

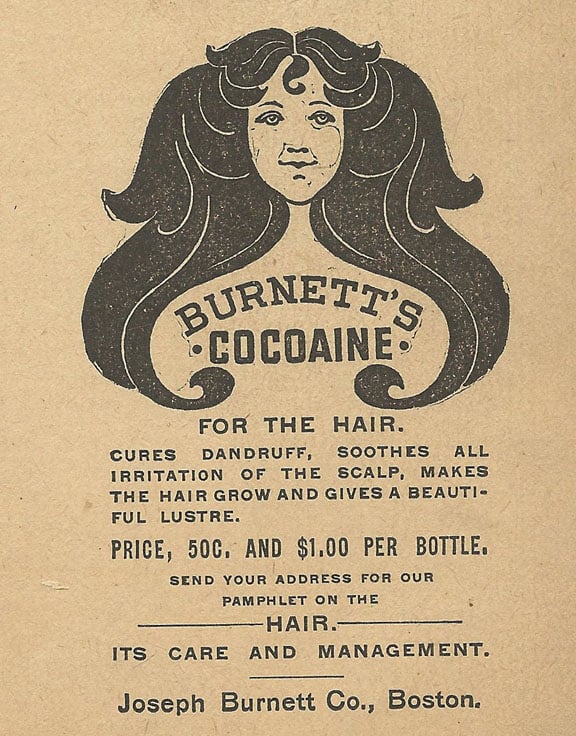

Not sure why I ended up here today. I may have thought of my BURDETTE’S COCOAINE (yes I spelled that correctly) bottle my brother Charles gave me years ago, before I started bottle collecting and losing my hair, or looking at some of the turn of the century celebrity photography by Napoleon Sarony earlier today (Read: The great work of Sarony, Major & Knapp Lithographer – New York). Anyway the winds changed and prompted a search for vintage cocaine advertising and related material. Nothing about cocaine could start without these lyrics which sound in my mind now.

The Song

If you wanna hang out you’ve got to take her out; cocaine.

If you wanna get down, down on the ground; cocaine.

She don’t lie, she don’t lie, she don’t lie; cocaine.

If you got bad news, you wanna kick them blues; cocaine.

When your day is done and you wanna run; cocaine.

She don’t lie, she don’t lie, she don’t lie; cocaine.

If your thing is gone and you wanna ride on; cocaine.

Don’t forget this fact, you can’t get it back; cocaine.

She don’t lie, she don’t lie, she don’t lie; cocaine.

Eric Clapton Cocaine Lyrics

BURNETTE’S COCOAINE, Two different sizes of the Burnett’s hair bottle. Both in aqua. Utah Antique Bottle Cliche

The Promise

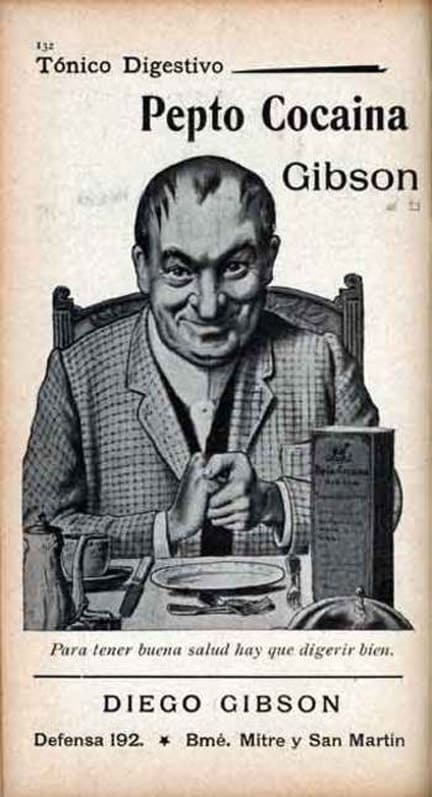

This sweating, anxious fellow, fidgeting with his hands, can’t wait for a dose of Pepto Cocaina to help that food go down

Cocaine is a highly addictive central nervous system stimulant extracted from the leaves of the coca plant, Erythroxylon coca. Coca leaves, the source of cocaine, were used by the Incas and other inhabitants of the Andean region of South America for thousands of years, both as a stimulant and to depress appetite and combat apoxia (altitude sickness).

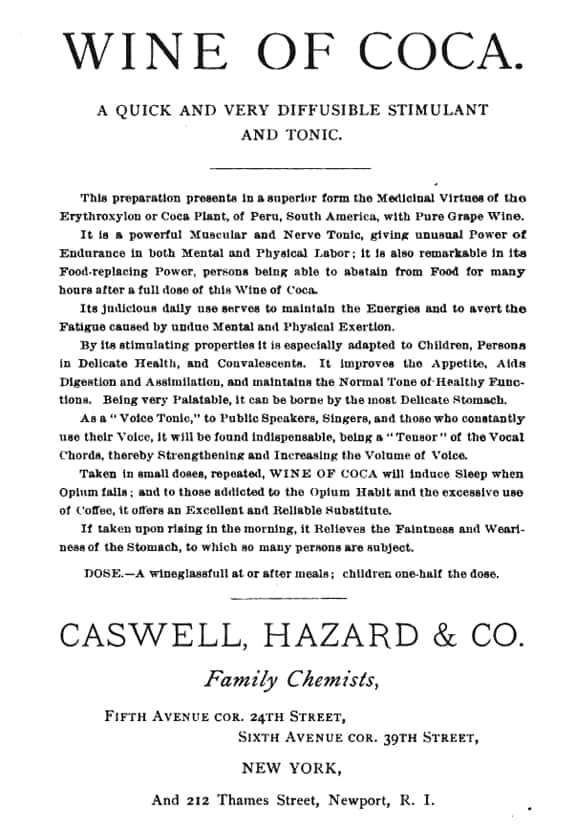

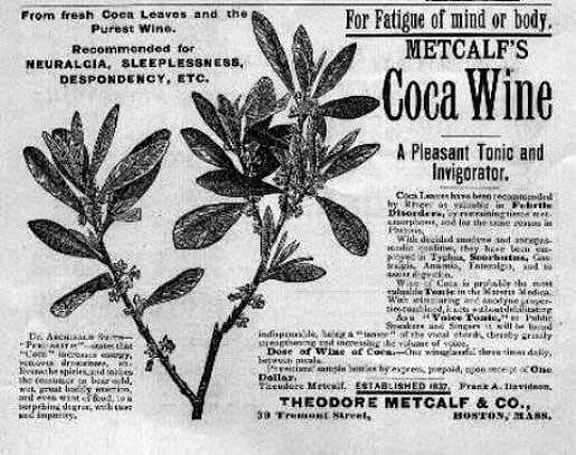

Metcalf’s Coca Wine, Coca wine combined wine with cocaine, producing a compound now known as cocaethylene, which, when ingested, is nearly as powerful a stimulant as cocaine.

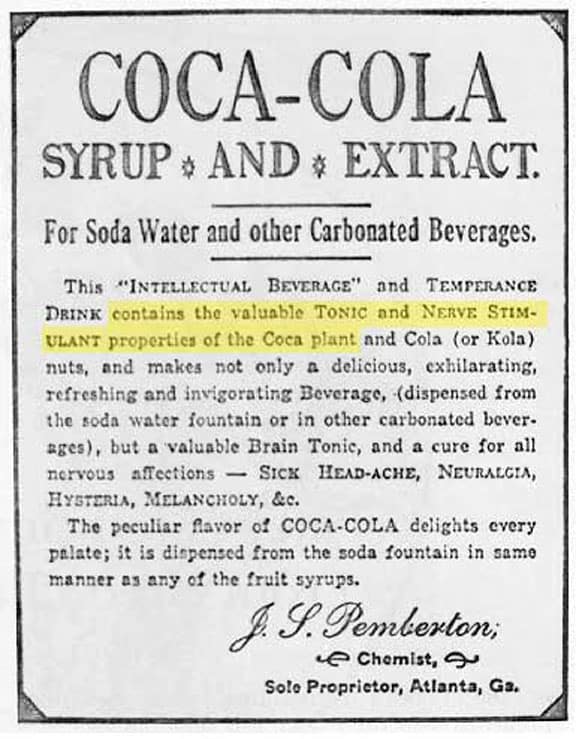

Despite the long history of coca leaf use, it was not until the latter part of the nineteenth century that chemist Friedrich Gaedcke first extracted the active ingredient cocaine hydrochloride from the leaves. The new drug soon became a common ingredient in patent medicines and other popular products and was soon sold over the counter in many forms at pharmacies until 1916. Sigmund Freud even described it as a “magical drug”.

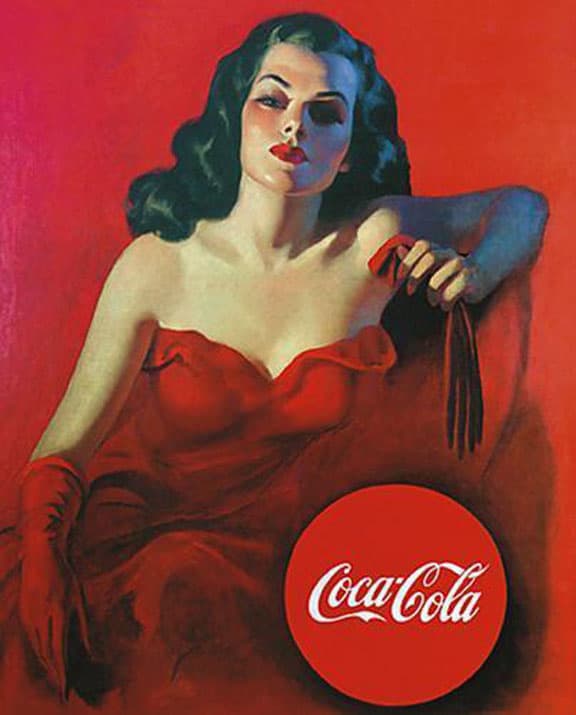

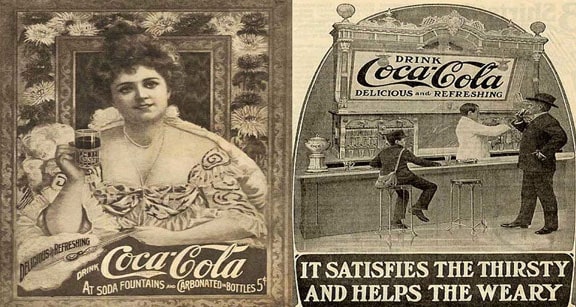

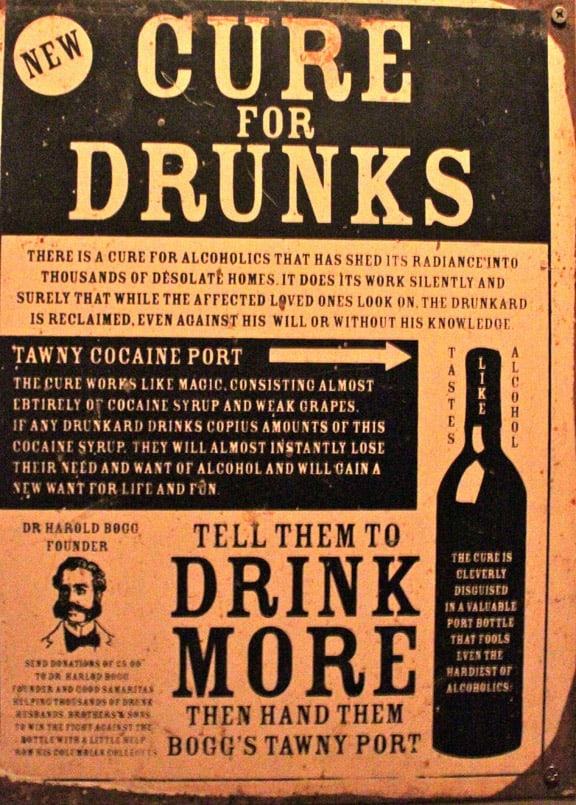

In the late 1800’s, and Early 1900’s, cocaine also was given to dock worker to help them work longer hours. During early attempts of the prohibition of alcohol, many encouraged people to drink cocaine, as a medicine or in the form of the fountain drink Coca-Cola. Some might try to downplay this now by saying it was in small amounts though cocaine was pretty much the main ingredient. This widespread use quickly raised concerns about the drug’s negative effects. In the early 1900s, several legislative steps were taken to address those concerns including the Harrison Act of 1914 which banned the use of cocaine and other substances in non-prescription products. In the wake of those actions, cocaine use declined substantially.

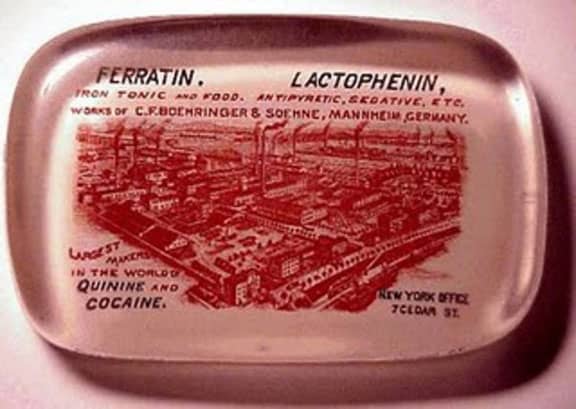

On this promotional paperweight, a German company boasts of being the “largest makers in the world of quinine and cocaine”

The Harrison Narcotics Tax Act

The Harrison Narcotics Tax Act (Ch. 1, 38 Stat. 785) was a United States federal law that regulated and taxed the production, importation, and distribution of opiates. The act was proposed by Representative Francis Burton Harrison of New York and was approved on December 14, 1914.

“An Act To provide for the registration of, with collectors of internal revenue, and to impose a special tax on all persons who produce, import, manufacture, compound, deal in, dispense, sell, distribute, or give away opium or coca leaves, their salts, derivatives, or preparations, and for other purposes.” The courts interpreted this to mean that physicians could prescribe narcotics to patients in the course of normal treatment, but not for the treatment of addiction.

Although technically illegal for purposes of distribution and use, the distribution, sale and use of cocaine was still legal for registered companies and individuals.

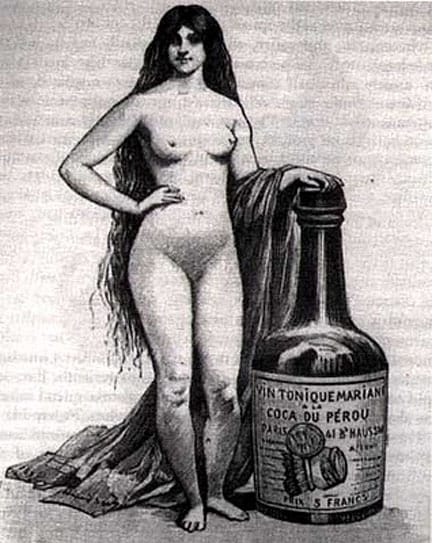

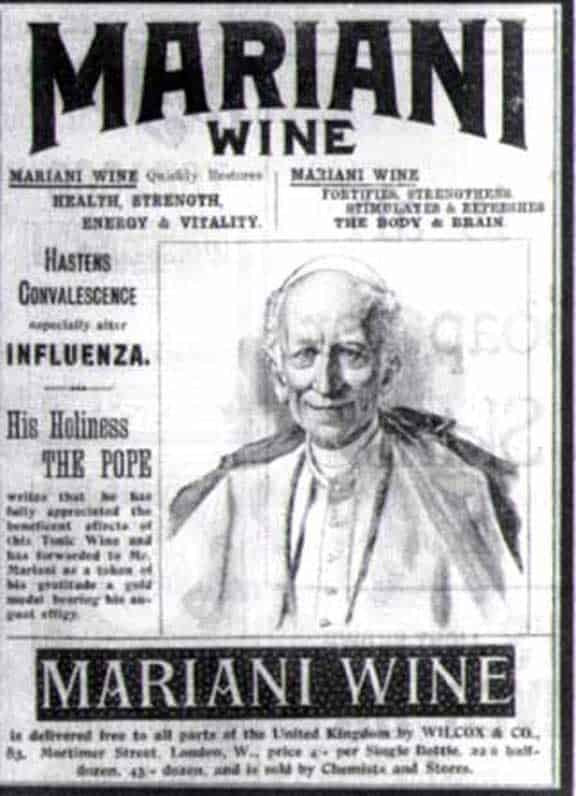

Vintage print ad for Vin Mariani. Image from cocaine.org. – Launched in Europe in 1863, the wine was launched by Corsican chemist and entrepreneur Angelo Mariani. After gathering information about the Inca and its love of coca, Mariani took up horticulture and began to grow the sacred Andean leaf in his backyard. Ingeniously, he sent samples of his new wine to famous people world wide in search of endorsements.Mariani’s outreach paid off: the businessman received glowing testimonials from the likes of Emile Zola, Thomas Edison, Buffalo Bill Cody, and even U.S. President William McKinley, Queen Victoria and three Popes. In 1885, when Ulysses Grant was in his final death throes and suffering from throat cancer, he drank coca wine. Reportedly, the treatment helped soothe his pain.

Pope Leo XIII purportedly carried a hipflask of the coca-treated Vin Mariani with him, and awarded a Vatican gold medal to Angelo Mariani. – Wikipedia

The Demise?

Cocaine seemed to be fazed out of the main stream by the 1930’s with the first drug laws and racial stereotypes of the drug. The drug culture of the 1960’s sparked renewed interest in cocaine. Eventually the drug made a comeback in the late 60’s and 70’s as a drug for the upper class. Cocaine seemed socially acceptable.

With the advent of crack in the 1980s, use of the drug had once again become a national problem. Cocaine use declined significantly during the early 1990s, but it remains a significant problem and is on the increase in certain geographic areas and among certain age groups. A mid-1990s government report said that Americans spend more money on cocaine than on all other illegal drugs combined.

The Children

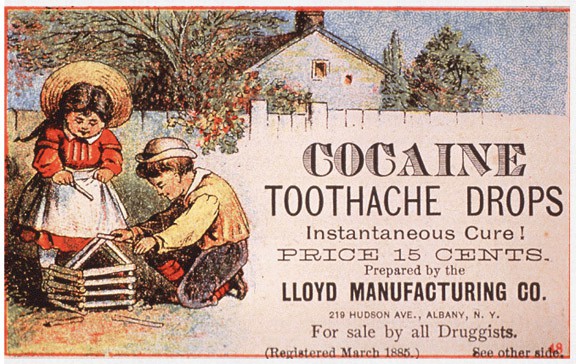

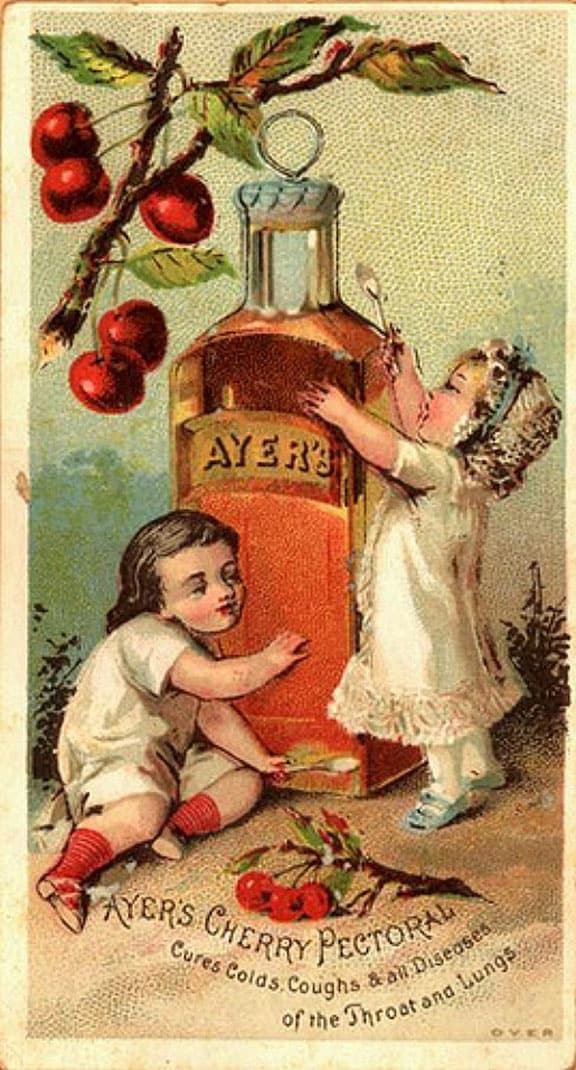

Lloyd Cocaine Toothache Drops – In the US, cocaine was sold over the counter until 1914 and was commonly found in products like toothache drops, dandruff remedies and medicinal tonics.

Cocaine was legal, even as late as this ad above (1885), and was not considered harmful in moderate doses. Many other drugs, now restricted by law, were also legal then, including opium, which was sold under city permit on the streets of Victoria.

In the nineteenth century many substances were used as medicines, some of which are now known to be harmful over the long term, such as mercury and lead. “Patent medicines”, like these Cocaine Toothache Drops, were very popular and required no prescription; they were indeed “For sale by all druggists.”

By the 1860s, the practice of medicine was going through many changes. The germ theory of disease was a controversial idea and not yet widely accepted. The first of the general anesthetics , chloroform and ether, had recently become available, making surgery potentially life saving rather than life threatening, though the routine use of antiseptics was still some years in the future.

Many medical practitioners still subscribed (at least in some form) to the ancient theory of the “four humors” developed by the Roman physician Galen (131-199 AD). According to this theory, the body is made up of four humors – blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. The relative amounts of each humor in the body determined state of health and temperament (a person with more blood was “sanguine”; with more phlegm “phlegmatic”; with black bile “melancholic”; and if yellow bile predominated, “choleric” or “bilious”). Too much or too little of any humor was said to cause illness, which could be cured by restoring the balance. Many nineteenth century medicines and practices were intended to do this. [source University of Victoria]

AYER’S CHERRY PECTORAL’S “magic” was in fact, due to its narcotic component, an opium derivative which at the time was a legal ingredient frequently used in medicines and available without restrictions. Ayer’s popular remedy received global acclaim, and was even shipped in special “ornate boxes” to foreign dignitaries. When James Cook Ayer retired in the early 1870s, he had acquired a vast fortune from his patent medicine industry and was considered the wealthiest manufacturer of patent medicines in the country.

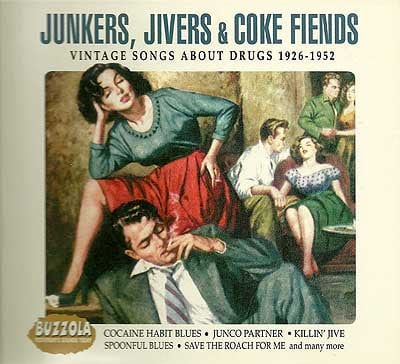

Images: The Culture

1895 Ad: Burnett’s Cocoaine For The Hair – Burnett’s Cocaine for the hair. Cures dandruff, soothes all irritation of the scalp, makes the hair grow and gives a beautiful lustre. Price 50c and $1.00 per bottle. Send your address for our pamphlet on the hair. Its care and management. Joseph Burnett Co., Boston.