James Campiglia, in a series of recent emails, embedded the following statement within one portion of his commentary which inspired this post:

“Also found a picture of a shard you may want to post. “Kintzing” early, beautiful green square is a rare one, might of contained bitters. I heard eleven are left in the case in the Bertrand Riverboat Museum. Rarities like this have kept us going.”

C.S. KINTZING ST. LOUIS MO. shard – OuthousePatrol.com

This got me researching the famous steamboat Bertrand and some of its cargo. I was also specifically looking for any reference to the KINTZING name and and bitters bottles that were in the cargo hold. Most bitters collectors are aware of the Hostetters Celebrated Stomach Bitters, Drakes Plantation Bitters, Kelly’s Old Cabin Bitters and Schroeder’s Stomach Bitters that were found. Here is the KINTZING booty list write-up from the Bertrand:

One case of 12 dark green, square bitters bottles of two kinds were recovered from the hold of the Bertrand. Eleven, 26-ounce bottles assigned to Subtype 6d are morphologically like the others in Type 6 except that one side is lettered vertically in raised letters to read: “C. S.KINTZING / ST LOUIS M°” Both Subtype 6d bottles and the single specimen assigned to Subtype 6e are so dark in reflected light that they look black in color. The 6e bottle is slightly taller than the bottles in Subtype 6d, and all four sides are plain; there are no marks whatsoever on this specimen. Dimensions, Subtype 6d: height, 8 7/8 inches; base, 2 13/16 by 2 13/16 inches; diameter of neck (outside), 1 inch, (inside), 11/16 inch. Dimensions, Subtype 6e: height, 9 3/4 inches; diameter of base, 2 7/8 inches; diameter of neck (outside), 1 inch, (inside), 3/4 inch.

Inasmuch as the contents of these bottles average 25 percent alcohol by volume, they are assumed to be bitters. The case in which they were shipped is marked in black stencil as follows: “1 DOZ”; consignee: “STUART & C°/DEER LODGE.“

Let’s look at what Wikipedia and others says about the Bertrand.

Excavation of the Steamboat Bertrand. The wreck of the steamboat Bertrand, located with supplies for the Montana gold fields, was excavated at DeSoto National Wildlife Refuge in 1968-69. This unique collection of artifacts is now on exhibit in the refuge’s visitor center near Missouri Valley, Iowa. – photo Sergeant Floyd River Museum in Sioux City

“Of the many shovels, shoes, and other items that include even a child’s chalkboard, perhaps the glass bottles capture the most attention. Collectors gasp at the elaborate designs on these once commonplace containers. The variety of sizes and shapes awe many who long to possess such antiques.”

Model of the Steamboat Bertrand – DeSoto National Wildlife Refuge

The Steamboat Bertrand

The steamboat Bertrand, carrying cargo up the Missouri River to Virginia City, Montana Territory, sank on April 1, 1865, after hitting a snag in the river north of Omaha, Nebraska. Half of its cargo was recovered 100 years later. Today, the artifacts are displayed in a museum at the DeSoto National Wildlife Refuge near Missouri Valley, Iowa. The display makes up the largest intact collection of Civil War-era artifacts in the United States.

History

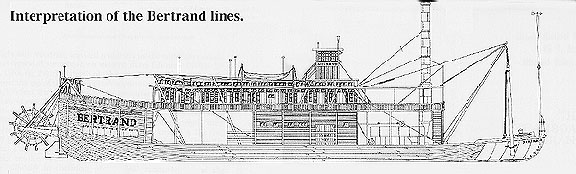

The Bertrand was launched in Wheeling, West Virginia in 1864. It measured 161 feet long, with a beam of 32 feet; its total burden was reported as 251 tons. A shallow-draft vessel, it drew only 18 inches when light, and perhaps no more than twice that when loaded.

Sources differ on the ownership of the Bertrand, but it probably belonged to the Montana and Idaho Transportation Line, based in St. Louis, Missouri. The firm was owned in part by John J. Roe of St. Louis.

On April 1, 1865, under the command of Captain James Yore, the steamboat struck a submerged log in the Desoto Bend of the Missouri River, about 25 miles upstream from Omaha, Nebraska. In less than ten minutes, it sank in 12 feet of water. No people died, but almost the entire cargo was lost; the estimated value of vessel and cargo combined was $100,000.

All cargo has been removed from the Bertrand in this aerial view. Photo: National Park Service – DeSoto National Wildlife Refuge

Over 100 years later in 1968, private salvagers Sam Corbino and Jesse Pursell discovered the wreck in the DeSoto National Wildlife Refuge, managed by the Department of Interior. Since the boat was found on government property, the men had to comply with the Antiquities Act of 1906. They had to give all of the artifacts to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for permanent preservation. The boat and over 500,000 artifacts excavated from the hold can be found at the museum of the DeSoto National Wildlife Refuge in the Missouri Valley, Iowa.

Transportation Systems and the Montana Territory

The Bertrand was part of a large water-based regional trading system that developed during the mid to late 19th-century. Only since 1859 had steamboats been traveling up the Missouri River to Fort Benton, Montana Territory. When gold was found in the Alder Gulch Claim in Montana in 1863, streams of hopefuls migrated to the area from other states; they created one of the most prosperous frontier cities: Virginia City, Montana Territory. Within a year of the find, more than 35,000 people would be living within a 10-mile radius of the discovery point.

J.J. Roe and his partners entered the shipping business in 1864, creating a line to ship goods up the Missouri River to the frontiers of the Montana Territory. J.J. Roe & Co. also invested in the Diamond R Transportation Co., which established a system of ox trains to bring goods to more remote locations some hundreds of miles from the river.

Prospectors and settlers created the demand for the goods that the steamboats were able to bring up the Missouri. By 1867, there were 113 different businesses registered in Virginia City to provide goods and services. Soon, the Alder Gulch Gold Camp grew into one of the largest frontier gold towns. It would prove one of the largest gold payoffs from the Rocky Mountains. The Missouri River was a major transportation route that sustained these Montana gold mines and the budding cities.

The Fur Trade

The river route was integral to the continuing fur trade between St. Louis and the Indian Country that provided American furs, which had been going on since the early nineteenth century. J.J. Roe & Co. consistently took goods upriver, and brought furs and other extractive materials back down the river. On one trip in 1865, the ship unloaded in St. Louis with 260 packs of furs.

The trip from St. Louis to this new Montana Territory took about two months and was often dangerous, due to encounters with the local Sioux Indians, but the profits were well worth the hardships. J.J. Roe entered the market with other merchants, businessmen and salesmen in this period, all earning their profits from supplying the demands of the settlers for consumable goods. This was an incredibly profitable economic niche on the frontier.

Look at thos Drakes Plantation Bitters! – DeSoto National Wildlife Refuge

Excavated Artifacts

The cargo found on the excavated Bertrand provides a unique glimpse into the material life of Virginia City, Montana Territory. The steamboat was full of clothing, tools, food and various consumer items on their way upriver. The ship’s cargo amounted to roughly 283 cubic meters, about half of which was recovered. The collection includes: dried and salted beef, mutton and pork; oysters; pepper sauce; strawberries, peaches and peanuts; mustard from France; 5,000 barrels of whiskey including bourbon; brandy and brandied cherries; and medicine bottles. There were over 3,000 textiles and clothing items, including gloves, hats, trousers and 137 men’s coats in seven different styles. Household goods included mirrors, clocks and silverware; and there were various building supplies for the growing town. The largest consignment of the goods was bound for the Vivian and Simpson retailer in Virginia City. They would have also been sold from log cabin stores in the surrounding towns, including that of Frank Worden, the founder of Missoula.

Objects from the riverboat Bertrand are kept in a temperature and humidity-controlled environment behind plexiglass. – DeSoto National Wildlife Refuge

Many of the goods were beyond the expectations for a primitive mining town. The ship also carried everything necessary to mine the Montana claim, including blasting powder, pickaxes and shovels. All the goods were fully insured, and the insurance company ultimately reimbursed the merchants for their losses. The men and women on the frontier were not totally isolated from the rest of the country and its consumption and fashion habits, but appear to have been relatively integrated and informed. The artifacts from the Bertrand represent the evidence of what kinds of goods flowed from St. Louis to the Montana territory during this important period of American state formation. More generally, water travel and the development of the steamboat played a major role in the settlement and development of America.

Read More: Legacy Magazine

Read More: Bottles on Montana’a Mining Frontier Ray Thompson

Read More: The Bertrand Bottles by Ronald R. Switzer

In Part 2 of this series we will look at the Hostetters Celebrated Stomach Bitters, Drakes Plantation Bitters, Kelly’s Old Cabin Bitters and Schroeder’s Stomach Bitters that were found.

So far, no other examples of the SCHROEDER’S SPICE BITTERS ladies leg are extant, other than the Bertrand cache. Doesn’t someone have just one Schroeder’s SPICE Bitters for me?? It is fun however, to occasionally find the early, large variant Schroeder’s with the word “SPICE” peened-out, yet faintly visible!

The Museum is on my list of places to go, things to see. Also, the book THE BERTRAND BOTTLES looks very worthwhile to own( not yet in my bottle library).

Note: Per the DeSoto Nat’l Wildlife Refuge homepage link, “Almost lost a second time”, all contents of the Museum were moved into remote storage in 2011 due to the flooding Missouri River attempting to reclaim it’s artifacts. Spooky; almost like a curse was put on the Bertrand’s contents for them having been removed from their resting place in the river.