THE INDIAN PRINCESS or LA BELLE SAUVAGE

“Even before the first Englishman set foot on Virginia soil, America was represented in the iconography of 16th century European art as an Indian woman. She was depicted as variously savage and seductive.”

Why do we call the bottles the ‘Indian Queen?’

24 September 2012

![]() I have always wondered why we call the figural Brown’s Celebrated Indian Herb Bitters and other similar bottles an ‘Indian Queen’ and in some cases ‘Indian Princess’. This prompted a search to look at some of the historical information and art that probably influenced the brand, bottle design and I suppose advertising (if I can ever find any). We will obviously be looking at Pocahontas and her lore.

I have always wondered why we call the figural Brown’s Celebrated Indian Herb Bitters and other similar bottles an ‘Indian Queen’ and in some cases ‘Indian Princess’. This prompted a search to look at some of the historical information and art that probably influenced the brand, bottle design and I suppose advertising (if I can ever find any). We will obviously be looking at Pocahontas and her lore.

Read More: Looking closer at the Brown’s Celebrated Indian Herb Bitters

Read more: Amethyst Indian Queen Found in Seattle

Read More: H. Pharazyn Indian Queen – Philadelphia

Read More: Mohawk Whiskey Pure Rye Indian Queen

Read More: E. Longs Indian Herb Bitters

Read More: The Indian Herb Bitters Prepared by Drs Dickerson & Stark

Read More: The Rubenesque Queens

Read More: Barrel series – Original Pocahontas Bitters

“The Discovery of America” (left), painted in 1575 by Jan Van Der Straet, depicting a naked Indian princess welcoming Christopher Columbus as she reclines on a hammock.

“The Discovery of America” (left), painted in 1575 by Jan Van Der Straet, depicting a naked Indian princess welcoming Christopher Columbus as she reclines on a hammock.

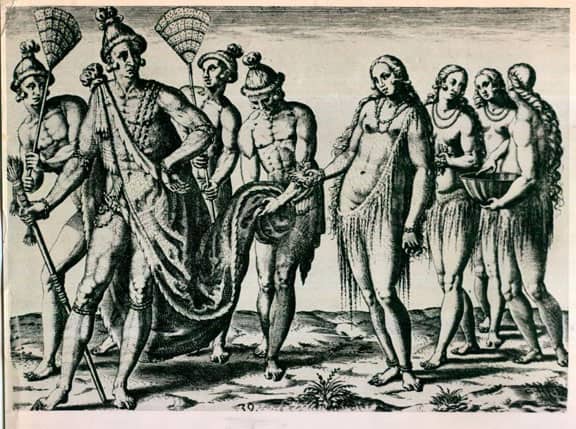

Even before the first Englishman set foot on Virginia soil, America was represented in the iconography of 16th century European art as an Indian woman. She was depicted as variously savage and seductive. Speculation as to the pre-civilized culture of the virgin continent fuelled the fascination with this Indian Princess, as the icon was called. When reports of Pocahontas’ valiant intervention on behalf of John Smith reached European ears, there must have been a slight shock of recognition. The legend of the savage, yet noble, Indian Princess already existed in an embryonic form before anyone had ever heard of Pocahontas. She essentially stepped into a ready-made iconic role.

A painting showing several warriors grabbing John Smith, and forcing him to stretch out on two large, flat stones. They stood over him with clubs, as though ready to beat him to death if ordered. Suddenly, in rushed the chief’s daughter, little Pocahontas, and took Smith’s head in her arms to save him from death. Pocahontas then pulled him to his feet and the chief declared that they were now friends. He then adopted Smith as his son, or a subordinate chief.

Pocahontas (1595?- 1617) – The daughter of a powerful Powhatan Indian Chief in Virginia, she was born in the Tidewater region of Virginia around 1595 and was called Matoaka. However, at an early age she took on the nickname of Pocahontas, meaning “Little-wanton,” for her playful and frolicsome nature, and was considered an “Indian Princess” in pop culture.

The Indian Princess was later used by the early republic to represent itself. President Washington , in 1790, ordered one of four early congressional medals to bear the image of the Indian woman. Thomas Jefferson was instrumental in bringing this work, now known as “The Diplomatic Medal” (see below), to fruition. He saw to it that a French engraver of some renown execute the medal, which bears the inscription “To peace and Commerce,” and depicts the United States as an Indian Princess holding a cornucopia filled with fruit. She is welcoming Mercury, symbolizing commerce, to her shores and seems to be calling his attention to bundles of merchandise ready for export displayed at her feet.

Augustin Dupré (1748–1833). Diplomatic Medal. Bronze original, 1791 The obverse of a diplomatic medal given out twice in 1792 to a pair of former French ambassadors to the United States, then discontinued. It was actually ordered in 1790 but not finished until early 1792. The medal was done by Augustin Dupré, a leading engraver in Paris at the time. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson suggested the basic design in his initial letter; Dupré chose to use it. The design is described as: TO PEACE AND COMMERCE. To the left, America, personified as an Indian queen, seated, facing the right, and holding in her left hand the cornucopia of abundance (Peace), welcomes Mercury (Commerce) to her shores, and with her right calls his attention to her products, packed ready for transportation. In the background, to the right, the sea, and a ship under full sail. Exergue: IV JUL. MDCCLXXVI.- Princeton University Library

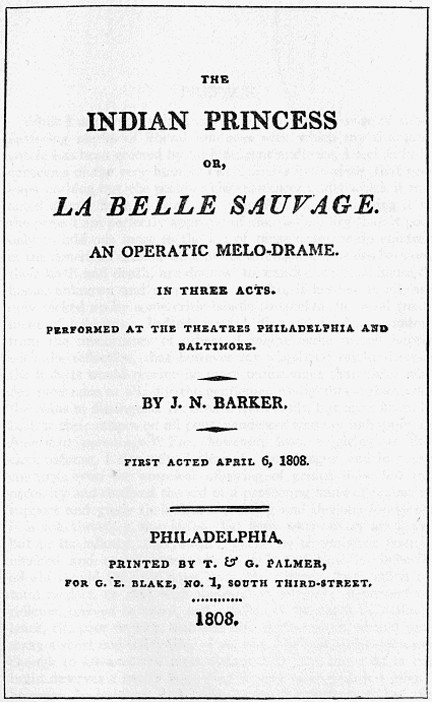

From The Project Gutenberg Book of The Indian Princess, by James Nelson Barker: Pocahontas then becomes inextricably linked to powerful image of the Indian Princess and its identification with the very essence of our nation. The 19th century, especially, saw a tremendous concern with Pocahontas as the United States sought to fashion a history for itself appropriate to its emerging identity.

I have selected his play, “The Indian Princess,”as an example of the numberless dramas that grew up around the character of Pocahontas. The reader will find it particularly of interest to contrast with this piece G. W. P. Custis’s “Pocahontas; or, The Settlers of Virginia” (1830), and John Brougham’s burlesque, “Po-ca-hon-tas; or, The Gentle Savage.”

The Indian Drama, in America, is a subject well worth careful attention. There are numberless plays mentioned by Laurence Hutton in his “Curiosities of the American Stage” which, though interesting as titles, have not been located as far as manuscripts are concerned.

Barker’s “The Indian Princess” is one of the earliest that deal with the character of Pocahontas. The subject has been interestingly treated in an article by Mr. E. J. Streubel (The Colonnade, New York University, September, 1915).

Barker had originally intended his play, “The Indian Princess,” to be a legitimate drama, instead of which, when it was first produced, it formed the libretto for the music by a man named John Bray, of the New Theatre. In his letter to Dunlap, he says:

“‘The Indian Princess,” in three acts … begun some time before, was taken up in 1808, at the request of Bray, and worked up into an opera, the music to which he composed. It was first performed for his benefit on the 6th of April, 1808, to a crowded house; but Webster, particularly obnoxious, at that period, to a large party, having a part in it, a tremendous tumult took place, and it was scarcely heard. I was on the stage, and directed the curtain to be dropped. It has since been frequently acted in, I believe, all the theatres of the United States. A few years since, I observed, in an English magazine, a critique on a drama called ‘Pocahontas; or, the Indian Princess,’ produced at Drury Lane. From the sketch given, this piece differs essentially from mine in the plan and arrangement; and yet, according to the critic, they were indebted for this very stupid production ‘to America, where it is a great favourite, and is to be found in all the printed collections of stock plays.’ The copyright of the ‘Indian Princess’ was also given to Blake, and transferred to Longworth. It was printed in 1808 or 1809. George Washington Custis, of Arlington, has, I am told, written a drama on the same subject.”

An account of the riot is to be found in Durang’s “History of the Philadelphia Stage,” and the reader, in order to gain some knowledge of the popularity of “The Indian Princess,” may likewise obtain interesting material in Manager Wood’s “Diary,” the manuscript of which is now in possession of the University of Pennsylvania. When the play was given in Philadelphia, the advertisement announced, “The principal materials forming this dramatic trifle are extracted from the General History of Virginia, written by Captain Smith, and printed London, folio, 1624; and as close an adherence to historic truth has been preserved as dramatic rules would allow of.”

It was given its first New York production at the Park Theatre on June 14, 1808.

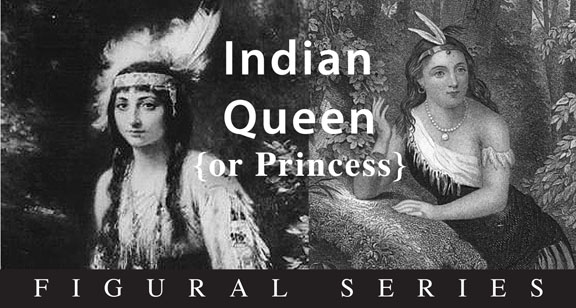

The ‘Indian Queen’ bottles are full of iconography, symbology and allegorical representations including a necklace, feathers, sword, shield and a crown. Here are some art pieces that may have influenced the two primary molds.

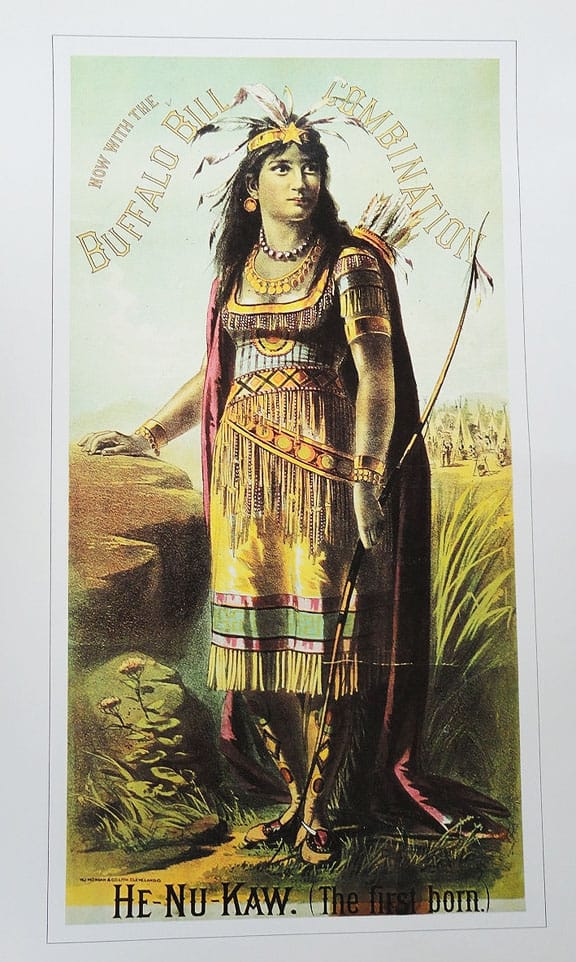

Vintage Buffalo Bill Wild West Poster, Indian Princess HE-NU-KAW print, Jack Rennert, Printed In America

John J. Barralet. “America Guided by Wisdom: An Allegorical representation of the United States, denoting their Independence and Prosperity.” Philadelphia, ca. 1815. The War of 1812 has often been called the “Second War of Independence,” especially at the time. Following a series of naval victories and battles at Baltimore and New Orleans, Americans were infused with a new optimism based on a peace treaty that arranged for them to be left alone to develop their new country. This print uses symbols of republican virtues to express pride in the new country. Six lines of descriptive text explain that the focus is on Minerva, Goddess of Wisdom, who points to an escutcheon of the United States with the motto “Union and Independence,” emblazoned on a shield held by America. Thrown down at their feet and behind them is a spear and shield with the visage of Medusa. To the right of this vignette is an equestrian statue of Washington at the entrance of a grand temple. To the left the god Mercury, representing commerce, points to proudly sailing ships to indicate his approval to the goddess Ceres, who holds wheat (a symbol of agriculture), while to her back are symbols of American industry: spinning, beekeeping, and plowing. This is a rich allegory to describe America. We date this print at 1815 because that year marked the end of the War of 1812, and the message is appropriate for that time. Also, in that year Benjamin Tanner (1775-1848) entered a partnership with Vallance, Kearney & Company whose names are added to a later state of this print as described by David M. Stauffer. So the imprint, as well as the wonderfully strong lines, suggests that this printing is a first state. This print is after a drawing by John James Barralet (ca. 1747-1815), an Irish artist who came to Philadelphia about 1795. He had established a reputation as a landscape and historical artist in Dublin and London. When Barralet first arrived in Philadelphia he was hired as an engraver by Alexander Lawson and soon took up painting landscapes in and around Philadelphia. Among American engravers, Barralet is credited with inventing a ruling machine for work on bank notes.

Sarah Winnemucca, whose Paiute Indian name was Thocmetony (Shell Flower), was famous for being a Native American educator, lecturer, tribal leader, and writer best known for her book Life Among the Piutes: Their Wrongs and Claims. This book is an autobiographical account of her people during their first forty years of contact with explorers and settlers. Sarah was a person of two worlds. At the time of her birth her people had only very limited contact with Euro-Americans; however she spent much of her adult life in white society. During the Snake and Bannock War Sarah served as an interpreter and negotiator between her people and the U.S. Army. Despite her influence, the Paiutes were moved to the Yakima Reservation in Washington. As a spokesperson for her people, she gave over 300 speeches to win support for them. In order to attract crowds, Winnemucca even dressed as an Indian princess. In this piece I decided to paint Winnemucca against Shell Flowers because she said, ” I am a shell flower, who could be as strong or as beautiful as me.” – Fine Art Silk Studio