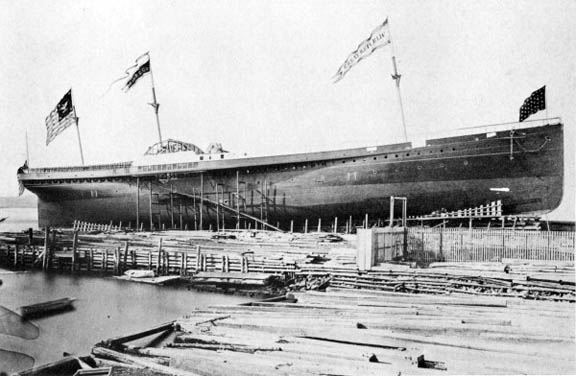

Constructed in 1853 and launched at Fells Point, Baltimore. Christened as the Tennessee on August 31.

BOTTLES ON THE

S T E A M S H I P S S R E P U B L I C

24 November 2012

![]() I wanted to circle back after honing up on the Steamboat Arabia (Read: Looking for Bottles Carried on the Steamboat Arabia) and Steamboat Bertrand (Read: Looking at some of the Bitters Bottles on the steamboat Bertrand – Part 1 and Looking at some of the Bitters Bottles on the steamboat Bertrand – Part 2 posts to look again at the bottles on the Steamship SS Republic. Over the years, these three ships and their booty have gotten intermixed in my mind and these posts have helped sort them out.

I wanted to circle back after honing up on the Steamboat Arabia (Read: Looking for Bottles Carried on the Steamboat Arabia) and Steamboat Bertrand (Read: Looking at some of the Bitters Bottles on the steamboat Bertrand – Part 1 and Looking at some of the Bitters Bottles on the steamboat Bertrand – Part 2 posts to look again at the bottles on the Steamship SS Republic. Over the years, these three ships and their booty have gotten intermixed in my mind and these posts have helped sort them out.

I have touched on the SS Republic before though more ‘tongue in cheek’. Read: Bottles From The Deep SS Republic Shipwreck Square Bitters Bottle on eBay and My Big Idea

SS Republic

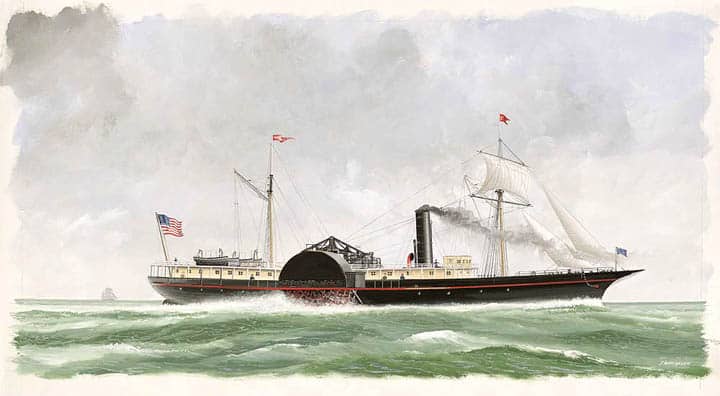

[Wikipedia] The SS Republic was a sidewheel steamship, originally named Tennessee (also named USS Mobile for a time). The SS Republic was lost in a hurricane off the coast of Georgia in October 1865, en route to New Orleans. In 2003, the wreck was located 100 miles off the coast of Savannah, Georgia. The artifacts are on display in selected museums, along with video stories about passengers and crew members.

Early Years

1853: Constructed and launched at Fells Point, Baltimore (see picture above). Christened as the Tennessee on August 31. First used as a merchant vessel in commercial service transporting passengers and cargo.

1855: The Tennessee was sent on the first trans-Atlantic crossing from Baltimore.

The ship, built in Baltimore, Maryland, for the famed War of 1812 Veteran, James Hooper, was launched in 1853, as the Tennessee. She began her service as a merchant vessel plying the Baltimore – Charleston route. Not long afterward, she was sent on the first trans-Atlantic crossing by a Baltimore steamship, sailing to Southampton, England, and Le Havre, France. A short time later Tennessee was used to open the first regular passenger steamship service between New York City and Central America.

1856: First regular passenger steamship service between New York City and Central America.

1856-57: Sailed the Nicaragua route transporting “49’ers” to the eastern shores of Panama and Nicaragua to travel to California’s Sierra Nevada mountains. The Tennessee delivered the last group of “immigrants” volunteering as mercenary soldiers for William Walker in Nicaragua.

During the California Gold Rush, the Tennessee transported “49’ers” to the eastern shores of Panama and Nicaragua to travel to California’s Sierra Nevada mountains. The Tennessee delivered the last group of “immigrants” volunteering as mercenary soldiers for William Walker in Nicaragua, and, after defeat of Walker’s forces, took home hundreds of disconsolate, defeated survivors.

1857: In commercial service transporting passengers and cargo from New York to New Orleans, and also from New Orleans to Vera Cruz, Mexico.

Tennessee for several years regularly served the Vera Cruz, Mexico – New Orleans route, often transporting immigrants to America as well as large sums of Mexican gold and silver. She was tied up in harbor at New Orleans when the American Civil War began on April 12, 1861.

Civil War Service

1861: At the outbreak of the Civil War the Tennessee was trapped in port at New Orleans, Louisiana, and was seized for use as a Confederate blockade runner as the CSS Tennessee.

At the outbreak of the Civil War she was trapped in port at New Orleans, Louisiana, and was seized for use as a Confederate blockade runner as the CSS Tennessee in 1861, although she was never able to escape blockade of the New Orleans harbor. After the Union capture of New Orleans, the ship was put into armed Union service, including as the flagship of United States Navy Admiral David G. Farragut for the conclusion of the Mississippi Campaign. As USS Tennessee, she was not only a fast and effective blockade ship in the West Gulf Squadron, but also a powerful gunship used to bombard Ft. Morgan during the Battle of Mobile Bay.

1862: After the Union capture of New Orleans, the ship was put into armed Union service, including as the flagship of United States Navy Admiral David G. Farragut for the conclusion of the Mississippi River Campaign.

1862-64: Other notable Civil War naval service included participation in the the Gulf Coast Blockade and the Battle of Mobile Bay.

1864: Name changed to USS Mobile after the Union’s Victory at the Battle of Mobile Bay to avoid confusion with the captured confederate ironclad also named Tennessee

In September, 1864, she was renamed USS Mobile to allow a famous Confederate armored ram ship to carry the name Tennessee after its capture. This second CSS Tennessee had been taken during a dramatic encounter at Mobile Bay. USS Mobile was damaged in a hurricane off the mouth of the Rio Grande in October, 1864, and sent to New York for repair. Upon inspection, the ship was judged too expensive to re-fit and was taken out of U.S. Navy commission in December, 1864. She was sold at auction in March, 1865, renamed SS Republic, repaired, and soon returned to the New York – New Orleans route hauling passengers and cargo. She was lost on her fifth civilian voyage after the war.

1865: Bought at auction by Russell Sturgis and investment group; repaired and refitted, then renamed the SS Republic and returned to a New York-New Orleans run in May

Wreck

October 18, 1865: The SS Republic leaves its New York pier bound for New Orleans loaded with a reported “$400,000 in specie.”

The Republic left New York on October 18, bound for New Orleans. According to her captain, she was carrying passengers and a cargo of $400,000 in coins, mostly in gold $10 and $20 pieces, intended for use as hard currency after the Civil War. The city of New Orleans, captured largely intact by the Union in 1862, had been the southern hub of Federal war efforts and was a thriving, busy city – but due to war, “hard money” (or gold and silver coin) was in very short supply.

October 23 1865: In the morning, the SS Republic encounters a gale which turns into a “perfect hurricane” before night, when the steamer was possibly off Carolina.

October 24, 1865: The paddlewheels stall and can’t carry the engine past dead center. The SS Republic is left powerless, drifting and at the mercy of the elements. Steam is raised on the donkey boiler to start the pumps.

On the fifth day of her voyage, a hurricane off the coast of Georgia proved too strong for the ship. By evening, her hull was leaking so badly that the fire in the boiler was extinguished, and she stalled in heavy seas, taking on water faster than her crew and passengers could bail her. At 4 pm on October 25, 1865, she sank. The passengers and crew escaped in four lifeboats and a makeshift raft, but 40-foot seas throughout the night made keeping them afloat a serious challenge. It was not until two days later, on October 27 that the survivors, now desperate with thirst, were found by the sailing ship Horace Beals. On October 29, the steamer General Hooker had been sent to look for the Republic, and rendezvoused with Horace Beals. The passengers were transferred and taken to Charleston. Most of the passengers and crew survived, although several were lost on the raft before they could be rescued. All the coins were lost.

October 25, 1865: At 9am, the “donkey boiler” fails and water pours into the hold. The crew begins work on a makeshift raft and prepares the lifeboats. At 1:30 pm the lifeboats and raft begin launching. At 4:00 pm, when all but 21 people were in the boats, the SS Republic sank suddenly. All passengers and crewmen safely make it into a lifeboat or raft except for two men who are last seen trying to swim through the ship’s floating debris. Captain Young is pulled down with the sinking ship, but he narrowly escapes and swims to the safety of a lifeboat.

October 26, 1865: Lifeboat #1, under the command of the Republic’s captain, is rescued by the brig John W. Lovitt.

October 27, 1865: Lifeboat #2 is rescued in the afternoon by the schooner Willie Dill. Lifeboat #3 is spotted and rescued late on the 27th by the barkentine Horace Beals.

October 29, 1865: Lifeboat #4 rescued after four nights at sea by the schooner Harper.

November 2, 1865: The raft, which departed with 14 to 18 people aboard, is spotted off Cape Hatteras by the U.S. Navy steamship, USS Tioga. Only two people remained on the raft to be rescued. The others disoriented by thirst and heat, leaped into the sea and drowned swimming toward what they falsely envisioned to have been land.

A photo mosaic image of the SS Republic steamship wreck, sunk in 1865, laying on ocean floor off Georgia, and assembled from hundreds of photos taken by Odyssey Marine Exploration’s remote-controlled submarine “Zeus.” – Odyssey Marine Exploration

Rediscovery

In August 2003, the wreck of the Republic was located by Odyssey Marine Exploration, Inc., a commercial archaeology company in Tampa, Florida. She was found about 100 miles southeast of Savannah, Georgia, in about 1,700 feet of water. A salvage effort recovered about one-third of the rare 19th century gold and silver coins carried aboard, worth an estimated $75 million. Most of the hull of the ship is now gone, but the rudder, parts of the paddle wheel and the steam engine are still present. The search and recovery effort was depicted in a National Geographic Society TV documentary Civil War Gold.

There is also a book about the search and recovery, Lost Gold of the Republic. Many artifacts, from the 14,000 salvaged, plus silver coins from the 51,000 coins collected, are on display in selected museums. Artifacts have been on display in Tampa, New Orleans, Detroit, Elberta, Hot Springs, and Oklahoma City. The displays also present video stories about passengers and crew members, and where they moved years after the wreck. Lifeboats had been found and rescued at different times.

SS Republic is currently the subject of a lawsuit over the gold recovery, as E. Lee Spence claims in a lawsuit that Odyssey Marine used his information in their efforts to locate the wreck. A judge in South Carolina has ruled that the case may proceed in that state, reversing his own earlier decision.

Reference: Odyssey Marine Exploration

Read: U.S. Gold Coins: Holding the California Gold Rush in the Palm of Your Hand

A variety of bottles and ceramic ware were discovered on the Republic wreck site. Nearly 14,000 artifacts were excavated; most were likely shipped as cargo, but some of the items such as the sturdy ironstone china featured here could have been used on the ship as well. – Odyssey Marine Exploration

Silver coins spill from an eroded wooden barrel on the SS Republic shipwreck site. – Odyssey Marine Exploration

A Drake’s Plantation Bitters bottle is excavated from the SS Republic shipwreck site, 1,700 feet below the ocean surface. A soft limpet suction device attached to the manipulator arm of Odyssey’s Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV), ZEUS delicately removes the bottle from the seabed. – Odyssey Marine Exploration

Bottles of beer recovered from the wreck of the SS Republic – Odyssey Marine Exploration

A bottle of berries, as found on the ocean floor amid the wreck of the SS Republic. – Odyssey Marine Exploration

Odyssey Marine Director of Conservation Fred Van de Walle shows a cathedral-pattered pickle bottle, one of 8,000 bottles taken from the wreck of the SS Republic.

1865 SS Republic Shipwreck Treasure Registered Bottle (see below) – on eBay now

1865 SS Republic Shipwreck Treasure Registered Bottle, more RARE than coins! – on eBay now

An assortment of glass bottles and artifacts recovered from the wreck of the SS Repulic, a small sampling of the over 14,000 bottles and artifacts excavated from the site. – Odyssey Marine Exploration

Lediard’s Morning Call Bitters Bottle. Lediard’s Morning Call was one of the may bitters bottles shipped aboard the SS Republic bound for New Orleans. The product of New York liquor merchant Charles lediard, the tonic was advertised as an “invigorating cordial bitter.” Less than a dozen examples were excavated from the site. – Odyssey Marine Exploration

A case gin bottle from the SS Republic, one of over 8,000 bottles recovered from the shipwreck site. – Odyssey Marine Exploration

Cathedral pickle bottles recovered from the SS Republic shipwreck site. These bottles once stored a variety of preserved foods important in the 19th-century American diet. – Odyssey Marine Exploration

Master ink bottles recovered from the wreck of the SS Republic were produced in varying shades of aqua, amber and green glass and feature a distinctive pouring spout for the efficient dispensing of liquid ink. – Odyssey Marine Exploration

Cathedral pepper sauce bottles recovered from the SS Republic shipwreck site. Pepper sauces were an important staple in 19th-century America, commonly used to season meat that had spoiled due to a lack of cold storage. – Odyssey Marine Exploration

Ferdinand,

Nice story! I’ve really enjoyed these shipwreck articles along with their cargo of bottles. Thanks for posting such interesting history associated with antique bottles.