S U B M A R I N E P O I S O N

B O T T L E S

“So that it may goe under water unto the bottome, and so to come up againe at your pleasure”

William Bourne – 16th Century submarine designer

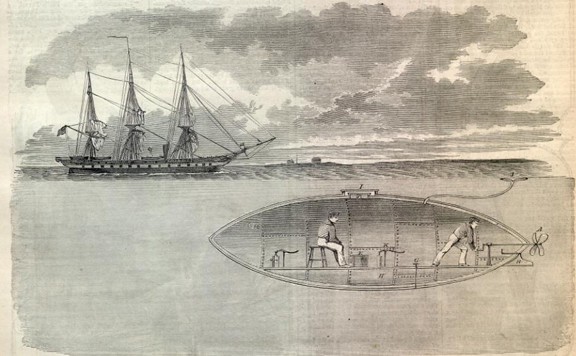

Civil War Submarine: A, Propeller.—B, Rudder.-C, Force-pump for ballast.—D, Dead light.—E, Torpedo.—F, Man-hole plate.—G, Cock to let water in the ballast-room.—H, Ballast-room.—I, India-rubber suction-plate.—J, India-rubber air-tube.-K, Foul-air pump. – Harper’s Weekly, November 2, 1861

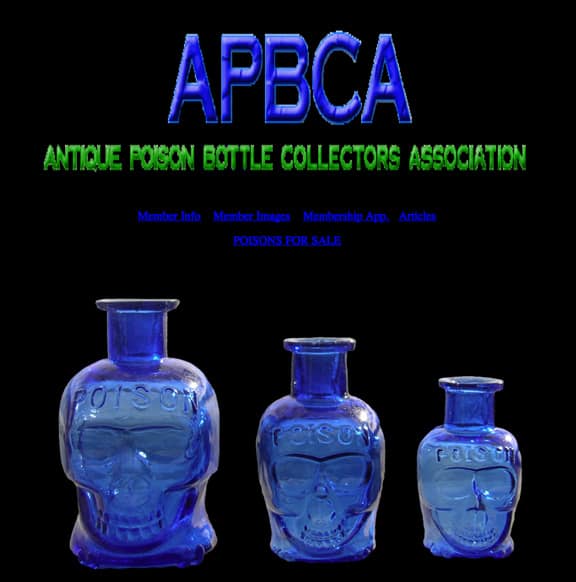

Some of you may not know this but my granddaughter Adriana is a member of the Antique Poison Bottle Collectors Association and my father; Ferdinand Meyer IV was a major poison bottle collector in the prime of his collecting days. Our home now has a few special areas of poison bottles that always seem to get attention when guests look at our bottle collection. Bright colors, interesting shapes, great embossings and good stories. This is what bottle collecting is all about.

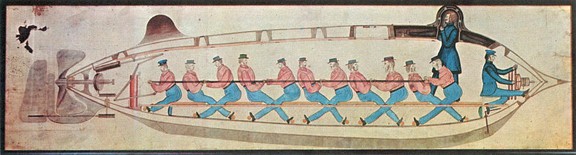

In recent posts I have written about skull and coffin poison figural bottles. Another drop-dead gorgeous poison bottle is the figural submarine or sub as they are sometimes called. You have to wonder, with the use of coffins and skulls for poison bottles, how this shape was developed? It is certainly distinct. I suspect the nickname ‘sub’ is appropriate because the submarine and torpedo were certainly making major news with the advancement of naval weaponry. Also, many of these early subs were stubby, fat and short and very unlike the later, sleeker designs. Read more: “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!”

Read More: Looking at Coffin Poison Bottles

Read More: Looking at Coffin Poison Bottles

Read More: Skull Shaped Poison Bottles – A frightening favorite

It seems like most of the poison bottles that we are familiar with date from the 1870s to 1930s. A good portion of the population at that time was illiterate, so accidental poisonings were a fact of life. Dim lighting in rooms was also a major consideration and it was not wise to take a drink of anything when you might stumble from bed looking for cough syrup and come across some poison instead in the medicine cabinet. A New York Times article dated May 11, 1913, reported a superintendent of a Missouri hospital ordered sleigh bells chained to the necks of bottles containing poisons after an attendant gave carbolic acid to a patient by mistake. The patient died, and the attendant was indicted.

Using sleigh bells, though attention getting was not the answer for a growing chemical industry in the late 1800s. England was experiencing an economic boom from the Industrial Revolution. Local chemists and druggists found they could produce cleaning compounds, insect killers, vermin poison, etc. cheaply enough to sell far and wide. Glass bottles, too, were inexpensive and perfect for transporting their contents to market, so the poison trade really began to take off. Reference: Collecting Poison Bottles

And so did the death rate. Both the governments of the United States and England enacted laws to prevent accidental poisonings. However, it was the poison manufacturers themselves who took direct action to save customers who, for instance, were fumbling for medicine by candlelight and grabbing bedbug poison by mistake. What they did, not only reduced the number of accidental deaths, but it also created an almost irresistible collectible.

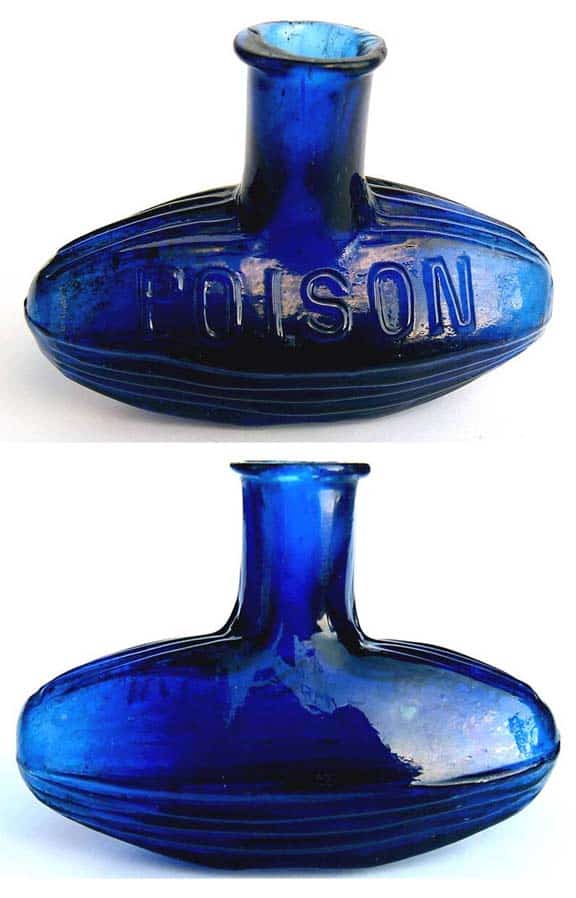

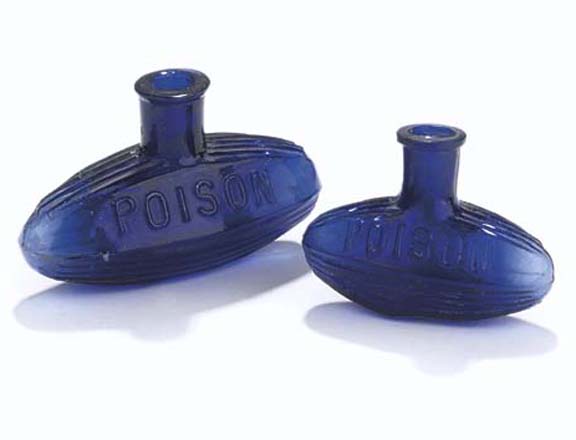

To distinguish them from non-lethal products, poison bottles were made unique and dramatic in color, texture and shape. Colors like cobalt blue, honey amber, black, and emerald and several other shades of green were used to ensure they stood out from the other bottles on the shelf.

Poison bottles were also designed with unique textures: latticework, raised ridges, dots, diamonds, horizontal or vertical ribbing, or hobnails. Also, embossed lettering warned, “DEATH,” “POISON,” “POISONOUS,” or “NOT TO BE TAKEN INTERNALLY.”

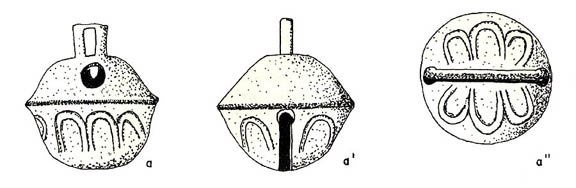

The bottle was described as “a bottle for the use of poisonous substances”

In England, cobalt blue “subs” bottles were invented by H. J. W. Martin and G. W. J. Walker in the fat cigar shape of a submarine. The bottle featured a long, vertical neck protruding from the center of the top and is embossed “POISON.” The bottle comes in three, four and five-inch sizes. Registered in 1899, the bottle did not for some reason, receive its letters patent till 1906 on April 12th. The bottle was described as “a bottle for the use of poisonous substances, made with there necks situated between.”

Reference: Rob’s Famous Poisons

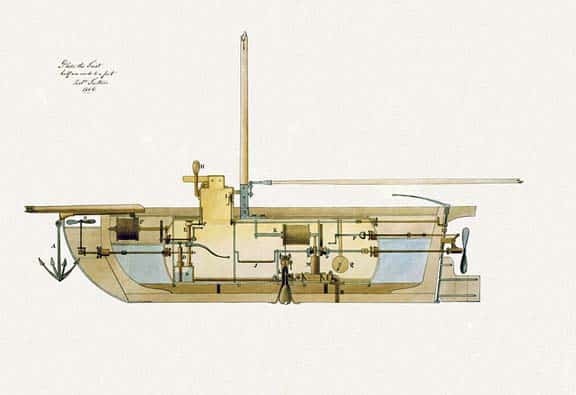

Submarine (“Submarine Vessel, Submarine Bombs and Mode of Attack”) for the United States government. Submarine vessel, longitudinal section. Scan from original engineering design in pencil, ink, and watercolor. 1806. – Library of Congress

“these ones rarely surface.”

collector and digger Taylor McBurney

SMALL SUBMARINE POISON. – Got this little beauty some years ago in Alans BBR Auction and i really love it,as it has a nice crude whippy thin lip and a nice long neck. And its not repaired!! Cheers Wayne. – Bottle Digging UK

Two early 20th-Century Bristol blue ‘Submarine’ poison bottles, with ribs, embossed POISON on one side and REGISERED NO 336907 on the underside — 10cm. (4in.) and 7.8cm. (3in.) wide (2) – Cristie’s

Three submarine POISON bottles and a Skull Poison Bottle – photograph by Daniel Palmer – Elsecar Heritage Center

Web site home page image for the Antique Poison Bottle Collectors Association (APBCA) – Joan Cabanis