LEADING UP TO BALTIMORE GLASS WORKS

Looking for some answers…

11 December 1012 (R•091515)

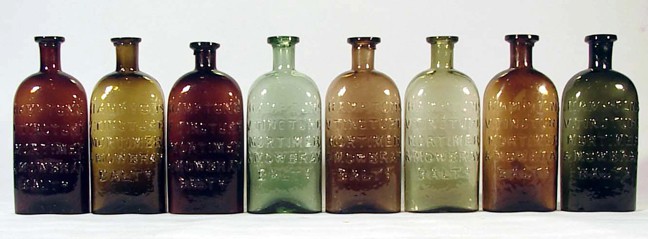

Baltimore flasks, Mr. Pollard says flatly, “come in the widest range of colors, the choicest tones of all.”

WILLIAM C. POLLARD

In Baltimore, glassmaking ranked as the third largest industry in the 19th Century.

![]() I have been contacted by Chris Rowell from the Baltimore Antique Bottle Club regarding providing pictures of Baltimore bitters bottles from my collection. Apparently the club will be updating their Baltimore Bottle Book. I am a member of the club and as many of you know, Baltimore is my hometown and close to my heart.

I have been contacted by Chris Rowell from the Baltimore Antique Bottle Club regarding providing pictures of Baltimore bitters bottles from my collection. Apparently the club will be updating their Baltimore Bottle Book. I am a member of the club and as many of you know, Baltimore is my hometown and close to my heart.

With this task in mind, I thought I would dig up some information and try to answer some questions that have been on my mind and “to do” list for some time. Basically what I would like to know is “why was Baltimore make such great glass?”,”what are the known Baltimore bitters?” and “who made, distributed and sold them?” I have many of the examples listed in the Baltimore Bottle Book but I need more information for my records and this assignment.

Baltimore Bitters Bottles (variants not noted):

ABBOTT’S BITTERS

BOGGS BITTERS (same as below)

BOGGS COTTMAN GERMAN TONIC BITTERS

GRANGER BITTERS

IRON BITTERS

BROWN’S IRON BITTERS

DR. DEGURLEY’S HERB BITTERS

DR. DECURLEY’S CELEBRATED HERB BITTERS (misspelling)

L. GOLDHEIM CELEBRATED SWISS WINE STOMACH BITTERS

MARYLAND TONIC BITTERS (paper label)

MORNING (5-pointed star) BITTERS

DR. PETZOLD’S GENUINE GERMAN BITTERS

RECORDS & GOLDSBOROUGH MORNING (eye) OPENER COCKTAIL BITTERS

DR. STONEBRAKER’S DYSPEPSIA BITTERS

L. M. LAROQUE’S ANTI-BILIOUS BITTERS

SCHROEDER’S GERMAN BITTERS

WHEELER’S BERLIN BITTERS

* orange represented in my collection

Origins and development of Baltimore Glass Works:

From Chronology of Glassmaking in Frederick County Maryland. Original Source: “In and out of Frederick Town: Colonial Occupations”, authored by Amy Reed on microfiche [6088329] LDS church, 975.288 H2

1759 – 1770: Jacob Frederick Dannwolf, a glassblower, and Peter Engel, a glass cutter had a small village type glassmaking concern in Frederick Town. Dannwolf died in 1771. Elsewhere, another German immigrant, William Henry Stiegel, arrived in Mannheim, Pennsylvania in 1750 and was eminently successful in the glassmaking industry from 1764 -1774.

Tuscarora Glass House

1771 – 1787: Entries in Joseph Doll’s ledger, beginning December, 1771, indicate that the Tuscarora Glass House (Tuscarora Creek being just off the Monococy River) was part of a small industrial complex that included a sawmill, a charcoal pit and coal house, a malt hill, and possibly a brewery. References to “Monococy ale” put up in bottles date back as far as 1753, but the type and origin of the bottles is not known.

The Foltz, Kramer, Everhart Glassworks

1778 – 1780: In 1778, German immigrants Balthazar, Adam, and George Kramer, Martin Eberhart and Conrad Foltz, formerly of the Stiegel Factory in Mannheim (which ceased activities in 1775) arrived in Frederick Town. In 1780 they formed a successful glasshouse partnership near Bennett’s Creek, which operated through 1784.

New Bremen Glass Manufactory of John Frederick Amelung

1784 – 1795: In 1784, Conrad Foltz died, and during the winter of 1784-85 when the glassblowing year ended in May, George Kramer and Margaret Foltz sold the land, the glasshouse, the equipment, and the inventory to John Frederick Amelung. Amelung, another German immigrant, acquired additional land, built a new glass-works and a complete community for his workers and called it New Bremen.

Much has been written about Amelung’s grand design for New Bremen, his successful appeals to Congress for financial support and his prolific expansion. It is said that at the peak of operations, he employed 400 – 500 skilled glass men recruited from Germany. But in short, his lofty ambitions, combined with a miscalculation of the American market appear to have outstripped his resources some time around 1795, at which time the business was passed on to his son, John Frederick Magnus Amelung.

Interestingly, an 1884 U.S. Census Office Report on the Manufacture of Glass states that “the works of Amelung were moved to Baltimore in 1788, and located on the South Side of the basin”.

The notion that Amelung’s Glass works was moved to Baltimore could be a mistaken reference to the Baltimore shop of Amelung’s son in law, Andrew Keener, who apparently was an agent for the sale of his bottles, including “green glass bottles from pint to gallons” as advertised in 1788 (McKearin, page 256).

The report also states that the Baltimore Glass Works was established at Federal Hill in 1790, but that “The Chronicles of Baltimore, page 236, makes the date 1799” so there appears to be some uncertainty about the ownership and establishment of the first Baltimore-based glass concern in the report.

Johnson and Aetna Glassworks

1787 – 1801: The Tuscarora glasshouse tract was transferred to Governor Thomas Johnson in 1787. The tract included the Johnson Glasshouse farm on Bush Creek (south of Frederick Town) and the nearby Aetna Glass works. Governor Johnson offered 800 acres of Tuscarora land for sale in 1793. A glasshouse, sawmill, tanning yard, and a grist mill were included in the advertisement. The 1798 tax record shows that the glasshouse was “out of repair” when William Goldsborough bought the land upon which it stood in 1801.

Like the Johnson’s Glassworks, the “Aetna” or “Etna” Glass House may also have been an outgrowth of the Tuscarora Glassworks. It too was part of the property put up for sale by Johnson in 1793, having made one 9-month blast prior to that time, but remained unsold.

Some time before 1799 Lewis Reppert (another German glassblower brought to New Bremen by Amelung) became superintendent of the Etna Works, which may have continued to operate until as late as 1810, or could have been sold as early as 1800.

As to the glass supplied to Baltimore merchants in the 1790’s, it would still appear to have been produced in Frederick County either by Amelung’s New Bremen Works near Bennet’s Creek, later by John Frederick Magnus and his partners Adam Kohlenberg and George Christian Gabler, or possibly by either the Johnson’s or the old Etna Works at Tuscarora Creek, the latter under the supervision of Lewis Reppert for a time. All four works were in production during the 1790’s.

But of the four, it is likely that Adam Kohlenberg’s “New Glasshouse”, built in 1796, may have continued the legacy of Amelung and the New Bremen Glass Manufactory into the 19th century.

Kohlenburg Glass Works

1796 – 1810: Adam Kohlenberg, a skilled glass blower who originally came to New Bremen with Amelung purchased property on Bear Creek around 1796. By virtue of the partnership with John Federick Magnus, the Kohlenburg Glass Works may have already succeeded the New Bremen Glass Manufactory in substance, if not in name, by that time.

In 1799 John Frederick Magnus formally transferred ownership of his father’s business to Kohlenberg and Gabler. On Varles 1808 map of Frederick County the Glass House is referred to simply as “A Kohlenberg / New Glass House”.

The Kohlenburg venture may have been successful enough to have been the glass works reported in the 1810 Frederick County census as producing “4,000 bottles per year”. If so, it had a longer history of production than New Bremen and its output would cross over into the era of the Baltimore Glass Works, established in 1799.

Baltimore Glass Works

1799-1880’s: The Baltimore Glass Works of Frederick M. Amelung & Company was the new venture of John Frederick Magnus Amelung, Alexander Furnival, Jacob Anhurtz and former Etna superintendent Lewis Reppert.

Though this initial partnership was ill starred from the outset, dissolving within three years partly due to the Amelung family debts that came with it, it can be said that the legacy of the early Frederick County glass artisans was carried over to the inception of the Baltimore Glass Works, which was to exemplify the style and characteristics of the German glassmaker’s trade for decades to come.

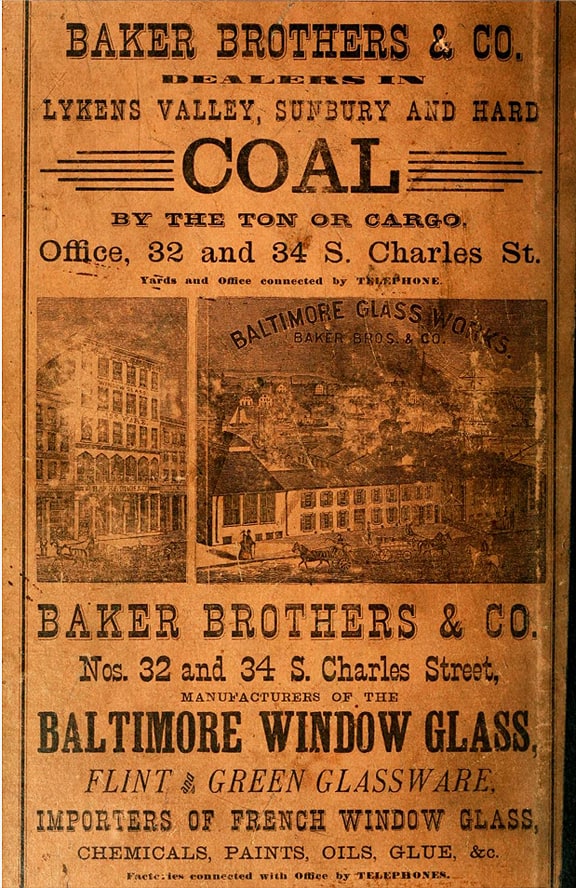

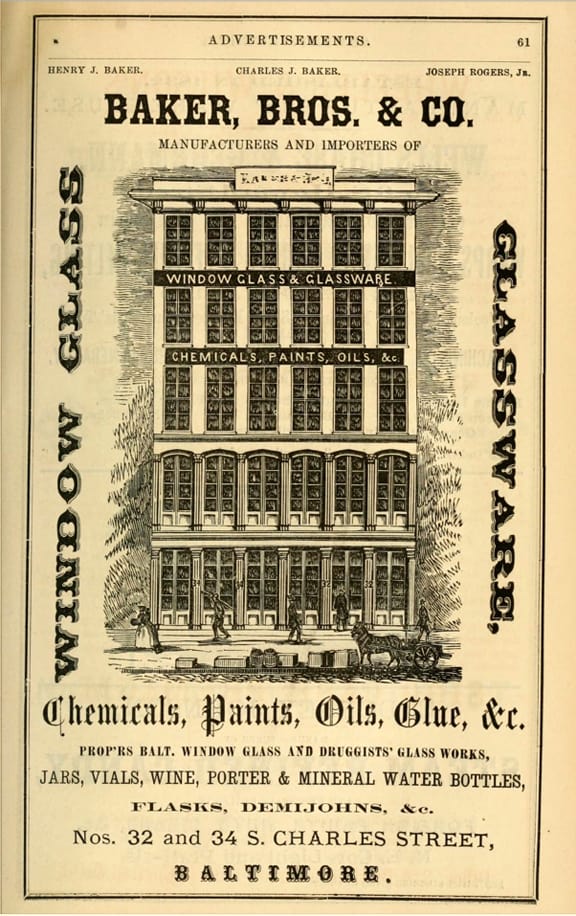

CHARLES JOSEPH BAKER, merchant and manufacturer, Baltimore, Md., born in Friendsbury, the family home near Baltimore, May 28, 1821, died Sept. 23, 1894. It is related that his grandfather, William Baker, having been left an orphan by an Indian massacre near Reading, Pa., came to Baltimore at the age of twelve and lived to found and carry on the successful house of William Baker & Sons. This trade gave direction to the labors of his children. In 1841, the subject of this memoir graduated from Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pa., where so many of the youth of Baltimore have gained an education, and entered the office of the window glass factory of his father, then doing business under the name of The Baltimore Glass Works. In 1842, his brother, Henry J. Baker, and he started a paint, oil and glass business. The brothers were hard working men, careful and shrewd, and met with marked success. As a branch of their business, they carried on the manufacture of glass for years in The Baltimore Window Glass, Bottle & Vial Works. The firm changed its name to Baker & Bro., in 1848, and to Baker Bro’s & Co., in 1851. In 1865, Mr. Baker bought the interest of his partners, his sons taking their place. Mr. Baker was a very capable merchant. He imported chemicals, oil, and glue and knew how to increase his business by promoting auxiliary local industries. He was connected with The Maryland White Lead Co., The Maryland Fertilizing & Manufacturing Co., The Chemical Co., of Canton, and other concerns. He was also interested in other enterprises merely as investments, including The Franklin Bank, of which he became a director in 1859 and in 1866 president; and The Canton Co., of which he was a director after 1860 and after 1870 the president, a position which he resigned in 1877. It was through his efforts that the Union railroad and tunnel were constructed; and, having bought control of The Baltimore Gazette, he was enabled to advance reform movements, which excited his lively interest. A man of probity, public spirit and great activity, Baltimore was the gainer by his labors. – America’s Successful Men of Affairs: The United States at large

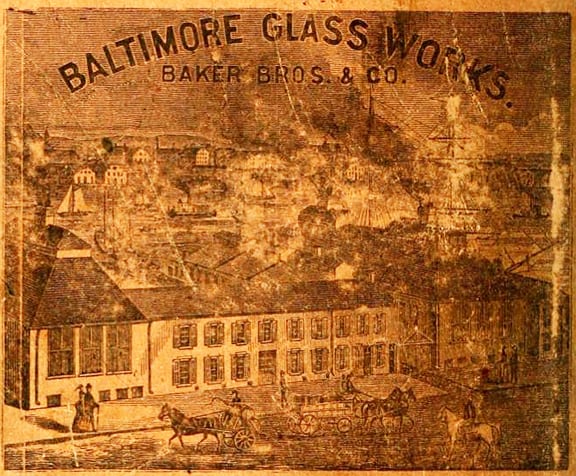

Federal Gazette, Aug. 11, 1802 – The site of the Baltimore Glass Works was on the harbor at Hughes Street (now Key Highway) between Henry and Covington Streets, where its successor company, the Federal Hill Glass Works of Baker Bros. & Co. remained as late as 1873.

Glassmaking in Baltimore

In Baltimore, glassmaking ranked as the third largest industry in the 19th Century.

An area of Federal Hill was once nicknamed “Glass House Row” or “Glass Hill” because of the glass workers who lived there. The glass industry flourished since at the time, glass, ceramics and stoneware were the few materials that could be used for creating safe, watertight containers for liquids. The Buck Glass Company was located at Fort Avenue and Lawrence Street. The Baltimore Glass Works had one operation in Federal Hill and another, named Spring Gardens Glass Works, located on Eutaw Street, on or around the site where the Raven’s football stadium currently stands.

Other companies in South Baltimore turned out window glass for houses and for mirrors, as well as stained glass for churches. The Maryland Window Glass Works was located at Leadenhall and Ostend streets, and Swindell Brothers was headquartered at Bayard and Russell streets.

Glassmaking was an active industry in Southeast Baltimore as well. The Maryland Glass Works was located in Fells Point at the northeast corner of Caroline and Lancaster streets. Another company in the same area was Baltimore Flint Glass Works, which was located on Lancaster Street. (Steve Charing)