Allen’s Landing – Houston (not everything is new here) – Part I

03 April 2013

H O U S T O N

On Monday February 17, 1840 at the regular City Council meeting a resolution was passed authorizing Mayor Charles Bigelow “to procure a seal to be styled, the seal for the City of Houston, Texas.”

At the next meeting, February 24th, “On motion of Alderman Stevens, it was resolved, that the seal purchased by F. Moore(e) Jr., Esq., be received as the city seal.”

Dr. Francis Moore, Jr. was a state senator and former mayor of Houston. It was he who had the original seal designed. The top half of the seal bore the words, “City of Houston.” The bottom half was originally empty. Dr. Moore was paid $50 for the seal, and “his honor the Mayor, caused the word ‘Texas’ to be cut on said seal.”

The center of the seal bears “The Lone Star, symbol of the newborn nation of the west…… the ‘Noble locomotive‘, heralding Houston’s spirit of progress; the humble plow, symbol of the agricultural empire of Texas, from which Houston would draw her wealth – by the iron rails.”

The original seal seemed to have disappeared until it was found in December 1939 by assistant city secretary, Mrs. Margaret Westerman, for whom the City Hall Annex is named.

S H I N Y & N E W

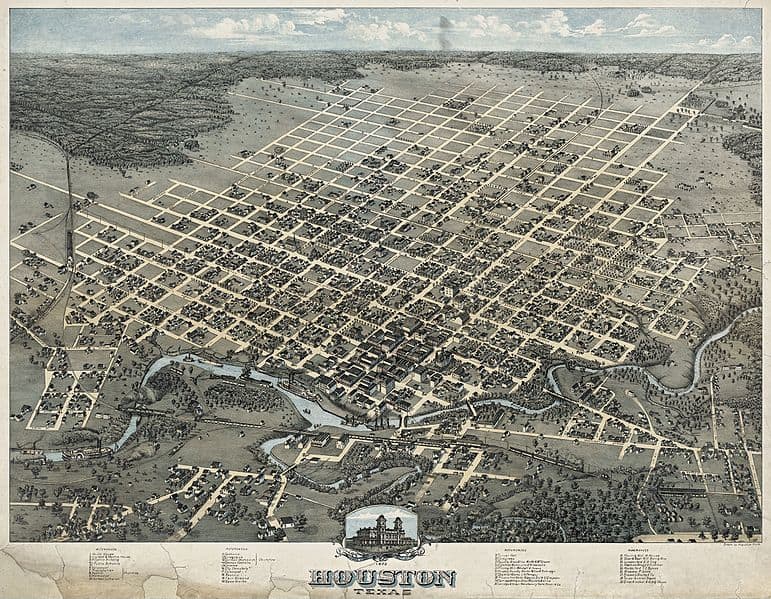

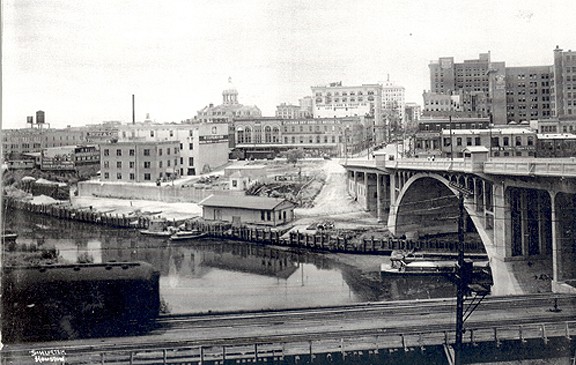

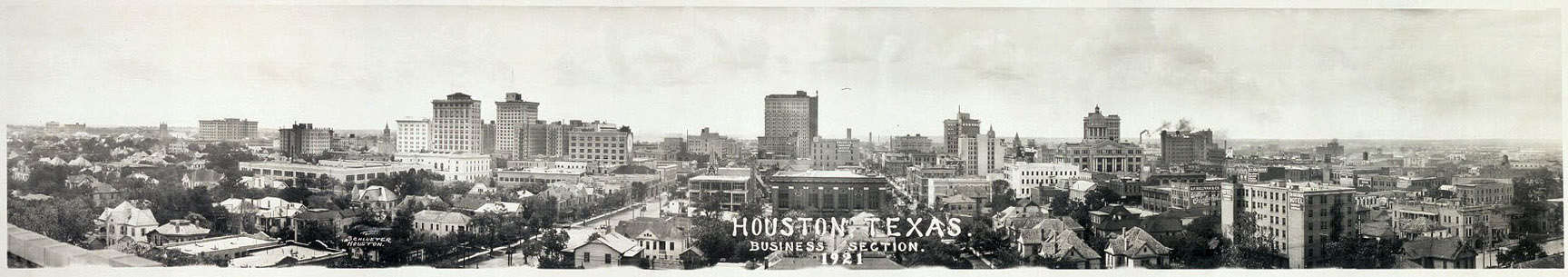

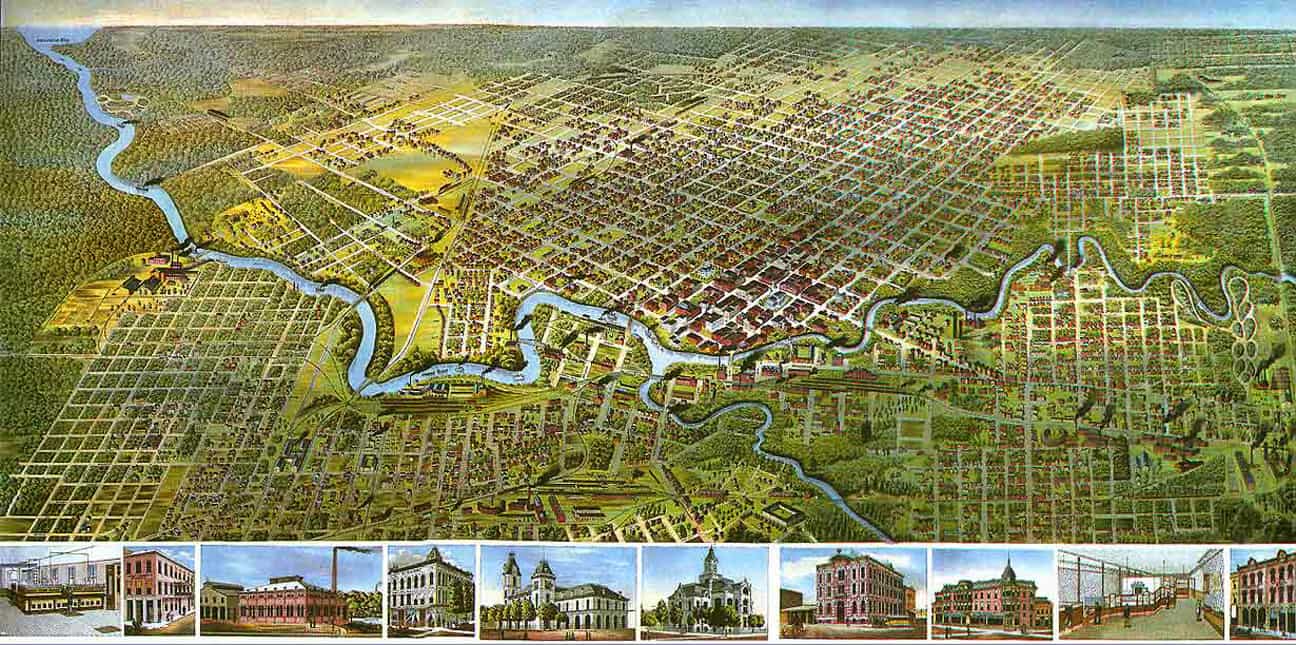

I have to admit, Elizabeth and I live in a great, huge city somewhat centrally located meaning I can hop on a plane and be almost anywhere in the country and world in short order. Houston has a reputation for being all shiny and new and of course, that is not the case. While it seems that there has been a mentality and mind set to tear something down and make something bigger (see 1921 panoramic above and recent skyline image), there are also areas embedded downtown that are just steeped in history. I see these hidden questions daily on my jogs, dog walks and general moving around. You see, I have lived downtown since 1983. I have been an antique bottle collector since 2002.

I have to admit, Elizabeth and I live in a great, huge city somewhat centrally located meaning I can hop on a plane and be almost anywhere in the country and world in short order. Houston has a reputation for being all shiny and new and of course, that is not the case. While it seems that there has been a mentality and mind set to tear something down and make something bigger (see 1921 panoramic above and recent skyline image), there are also areas embedded downtown that are just steeped in history. I see these hidden questions daily on my jogs, dog walks and general moving around. You see, I have lived downtown since 1983. I have been an antique bottle collector since 2002.

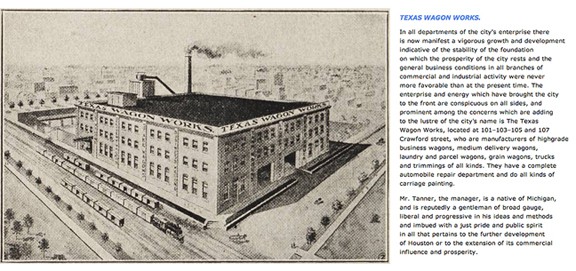

Texas Wagon Works before becoming Eller Wagon Works (see below). My design offices for FMG Design are located within this building on the first floor. The train tracks are beneath Commerce Street now. The building is on a raised dock platform.

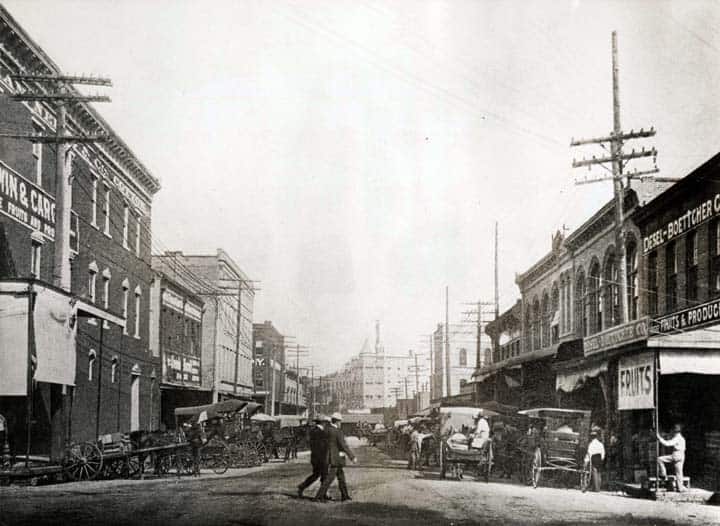

My office here at FMG Design is in the old Texas and Eller Wagon Works Building on Commerce Street (see above illustration). There is actually a picture of Commerce Street further below. The asphalt now covers the old railroad tracks that ran down the street and serviced all the business and warehouses along Buffalo Bayou which connects to the Houston Ship Channel and then the Gulf of Mexico (see map below).

The purpose of this series is reflect back on the beginning of Houston and how Houston relates to antique bottle collecting. We get the history all the time from the New Englanders and the San Francisco Bay area collectors (among many other bottle rich locales) but rarely do we hear of Texas and specifically Houston. Where are the saloons, the groceries, bottlers and liquor merchants. If I was a bottle digger, where would I look? What was under or prior to the newer buildings? In Part I we will look primarily at Allen’s Landing. In Part II we will look at what was happening at and around Allen’s Landing.

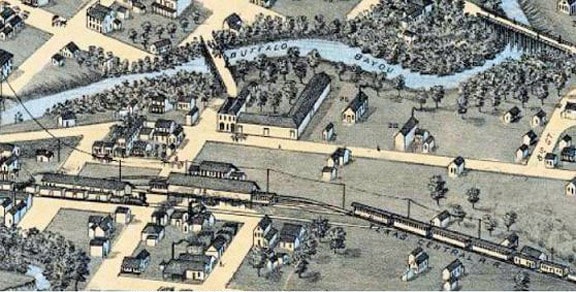

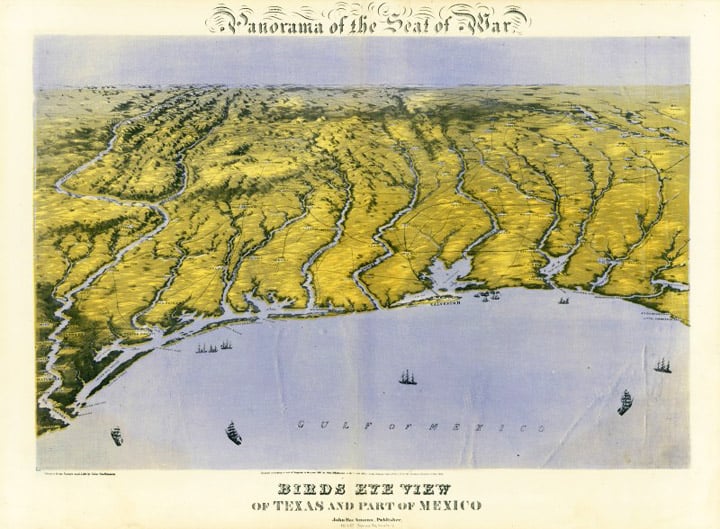

Panorama of the Seat of War: Bird’s Eye View of Texas and Part of Mexico. A Perfect Recreation of the tinted lithograph. John Bachman. 1861. If you look carefully in this map, you will see Galveston and Galveston Bay. The Buffalo Bayou runs from Houston downtown to the bay and Houston Ship Channel. – Discovery Edition Maps

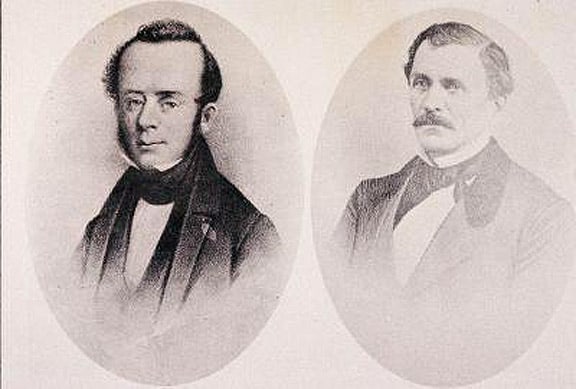

T H E A L L E N B R O T H E R S

Houston is the fourth most populous city in the United States, and the most populous city in the state of Texas. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, the city had a population of 2.1 million people within a land area of 599.6 square miles. This is huge compared to most cities.

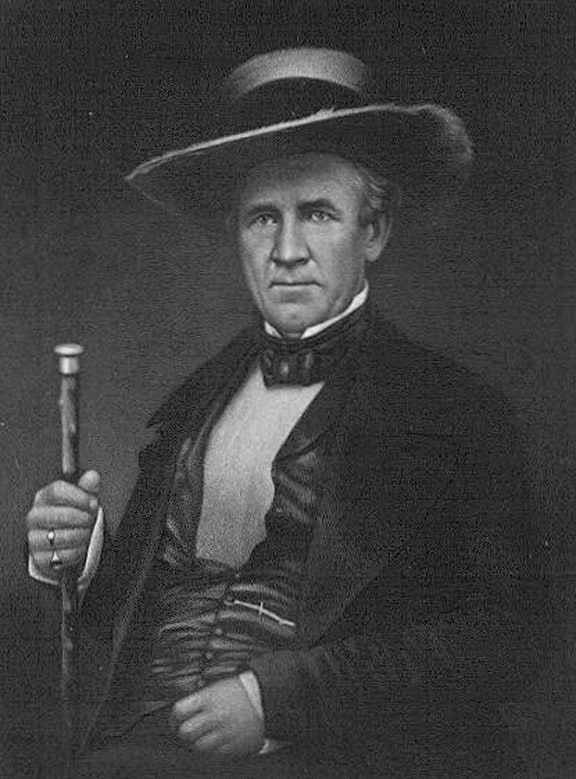

G E N E R A L S A M H O U S T O N

Houston was founded in 1836 on land near the banks of Buffalo Bayou, now known as Allen’s Landing and incorporated as a city on June 5, 1837. The city was named after former General Sam Houston, who was president of the Republic of Texas and had commanded and won at the Battle of San Jacinto 25 miles east of where the city was established. The burgeoning port and railroad industry, combined with oil discovery in 1901, has induced continual surges in the city’s population. In the mid-twentieth century, Houston became the home of the Texas Medical Center—the world’s largest concentration of healthcare and research institutions—and NASA’s Johnson Space Center, where the Mission Control Center is located.

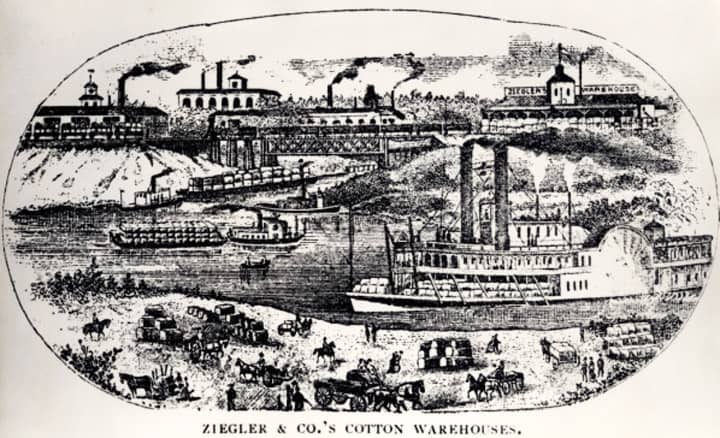

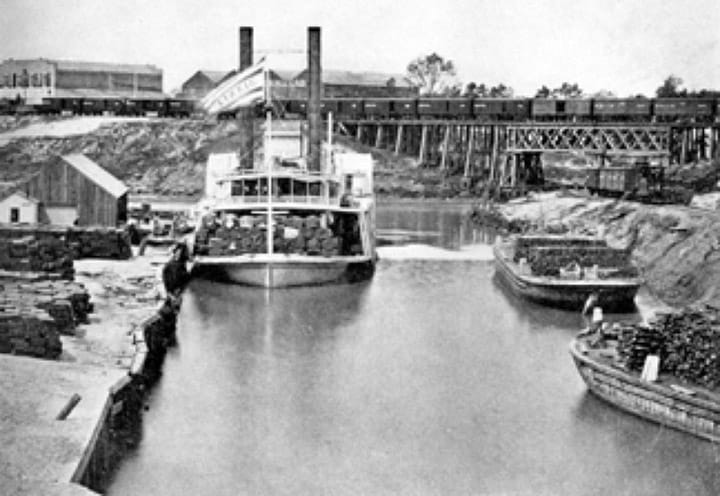

Photograph of a printed engraving illustrating the port of Houston looking north from Allen’s Landing across Buffalo Bayou. A side wheel paddle boat and barges towed by boats are all loaded with cotton. A train, also loaded with cotton bales, is crossing the bridge over White Oak Bayou. The Ziegler Warehouse stands in the top right of the illustration. The picture is labeled “Ziegler & Co.’s Cotton Warehouses.”

A L L E N ‘ S L A N D I N G

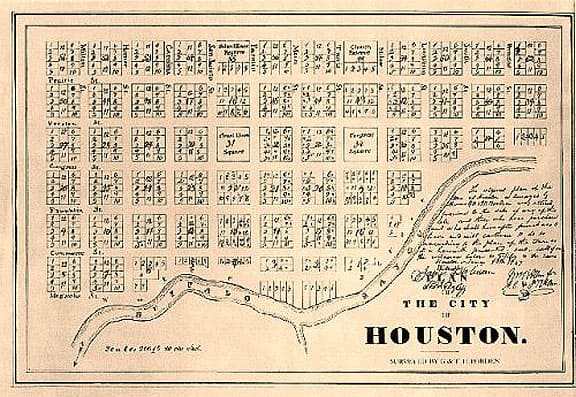

Allen’s Landing is the birthplace of the city of Houston. In August 1836, just months after the Republic of Texas won its independence from Mexico, two brothers (and real estate developers) from New York – John Kirby Allen and Augustus Chapman Allen – purchased 6,642 acres in the area and settled there on the banks of Buffalo Bayou. The campus of the University of Houston–Downtown sits atop Allen’s Landing. Allen’s Landing is at the confluence of White Oak Bayou and Buffalo Bayou and serves as a natural turning basin. A dock was quickly opened on the site, and the steamer Laura was the first ship to anchor at the landing on January 26, 1837. The landing was officially named a port in 1841 – the original Port of Houston. In 1910, the United States government approved funding for the dredging of a ship channel from the Gulf of Mexico to the present turning basin four miles to the east of Allen’s Landing. [Wikipedia]

“consisted of one dugout canoe, a bottle gourd of whisky and a surveyor’s chain and compass, and was inhabited by four men with an ordinary camping outfit.”

Dilue Rose Harris, in her memoirs recalling the days after the Battle of San Jacinto in 1836, wrote of the excitement that the proposed new town of Houston was creating among the people returning to Texas after the defeat of Santa Anna. In early June, 1836, some of the young men from the Stafford Point community (now, modern Stafford) rode over to Buffalo Bayou to check out the new town described in the circulars and handbills distributed by the Allen brothers. What they found there became more of a joke than anything else. The town, which was difficult to locate among the pine woods, “consisted of one dugout canoe, a bottle gourd of whisky and a surveyor’s chain and compass, and was inhabited by four men with an ordinary camping outfit.” That’s where the story takes a ominous turn. To escape the heat and the swarms of mosquitos, the men decided to take a swim in the bayou. No sooner had they all gotten into the water, when the “water was alive with alligators.” Three of the men got out on the south bank of the bayou from whence they entered, but one exited on the other side. Those on the south bank got a canoe and rescued him, bringing the separated man back to the south side. Not only did the man face death at the jaws of the alligators, but, he told his rescuers that while he was waiting for them, a large panther was lurking nearby. The big cat ran off as the canoe approached. By the end of the nineteenth century, Buffalo Bayou as a major shipping lane was on the decline. Ocean going vessels exchanged cargo at docks below the turning basin, and the traffic upstream to Allen’s Landing was primarily that of barges. By the turn of the twentieth century, the bayou has little or no commercial traffic. It is time to return the bayou to the canoes. Buffalo Bayou – An Echo of Houston’s Wilderness Beginnings by Louis F. Aulbach

B U F F A L O B A Y O U

Houston Map 1981 – Here you see the confluence of White Oak Bayou and Buffalo Bayou that for awhile served as a natural turning basin. Buffalo Bayou leads to the Gulf. Allen’s Landing is pretty much at the confluence.

E A R L Y A L L E N ‘ S L A N D I N G

P H O T O G R A P H S

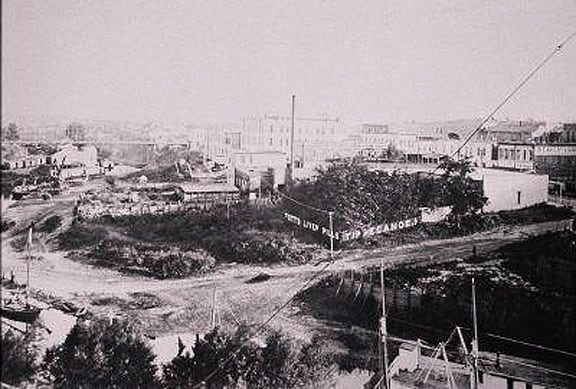

Commerce Street, 1890, the “heart of produce row.” Photo from the George Fuermann “Texas and Houston” Collection, courtesy of Special Collections, University of Houston Libraries. My office is on Commerce Street.

Cargo offloading or onloading on Buffalo Bayou at Allen’s Landing in downtown Houston. Sometime around the turn of the century.

Historic Allen’s Landing. Look carefully at the “Liver Pills Tippecanoe” graphics on the fence. I can not read the first word.

Barge traffic at the warft at Allen’s Landing (left) with the White Oak Bayou entering on the right (c. 1911) – Photo courtesy TxDOT

Read Part II: What was here, Early Houston Advertisements – Part II

Read Part IIA: What was here, Early Houston Advertisements – Part IIA