N. K. Brown’s Iron & Quinine Bitters

Burlington, Vermont

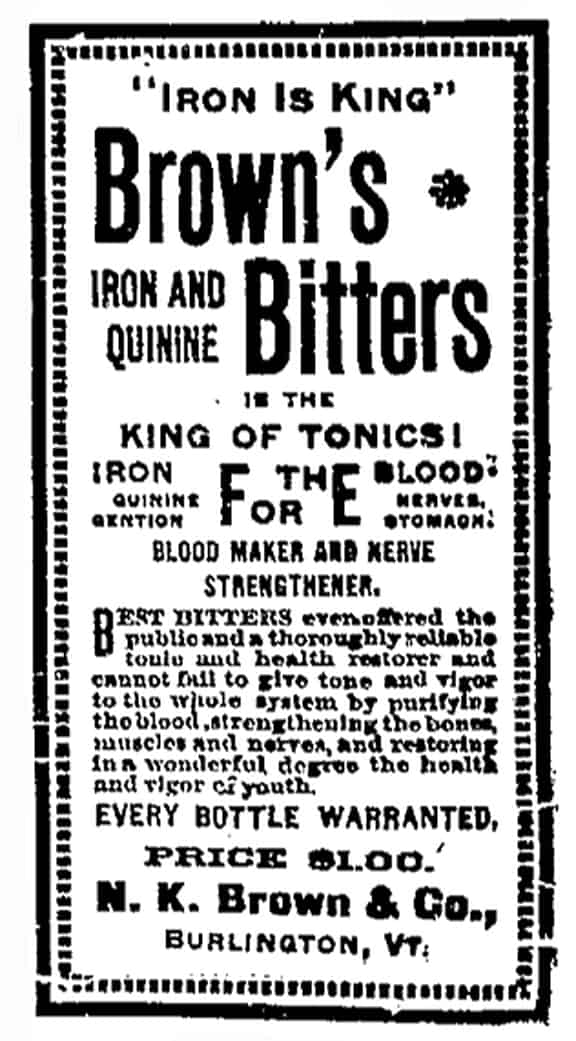

“Iron is King” Brown’s Iron & Quinine Bitters is the King of Tonics!

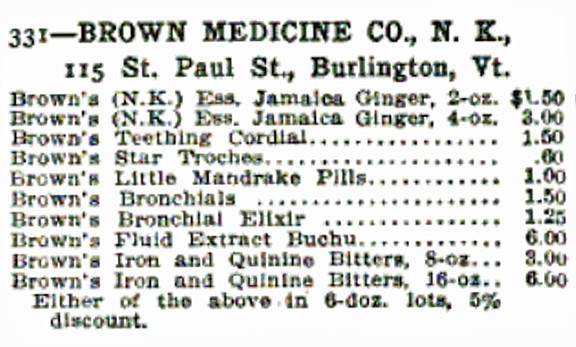

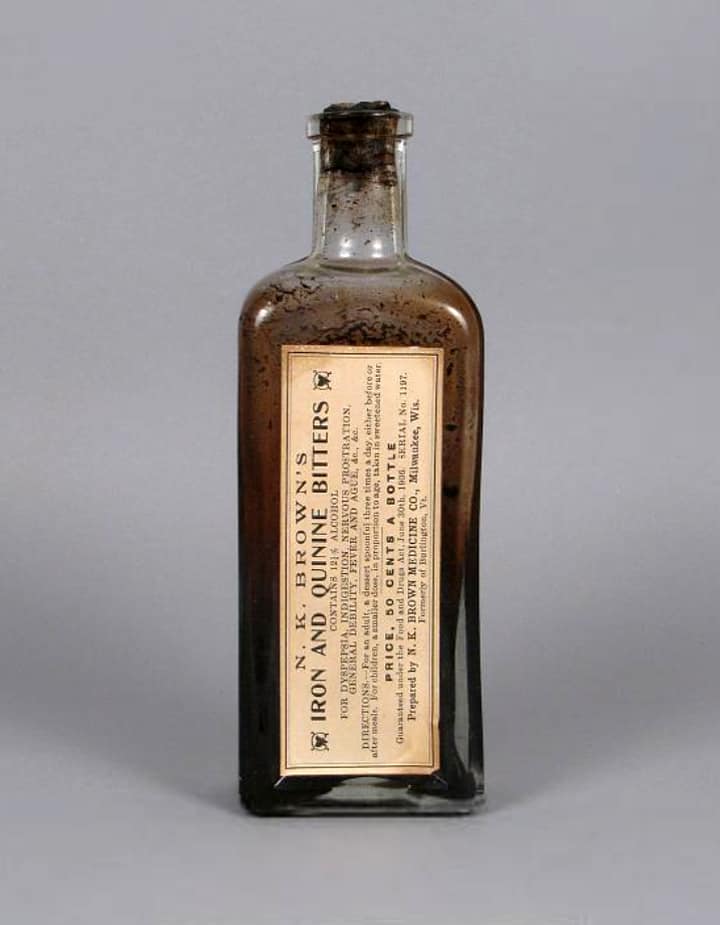

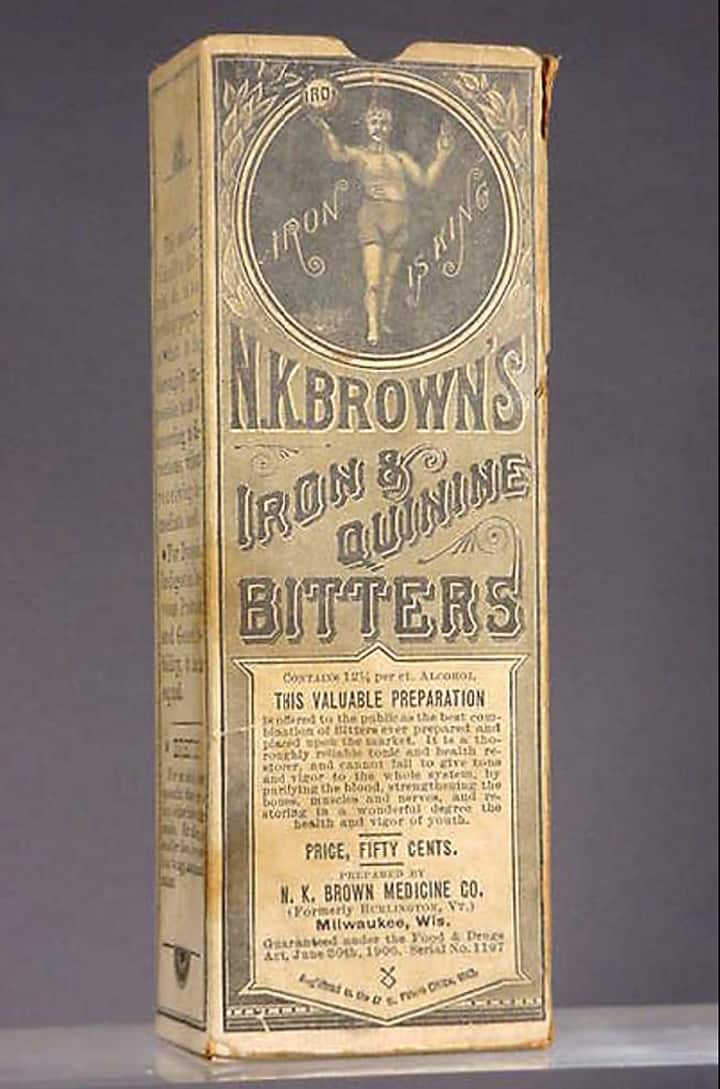

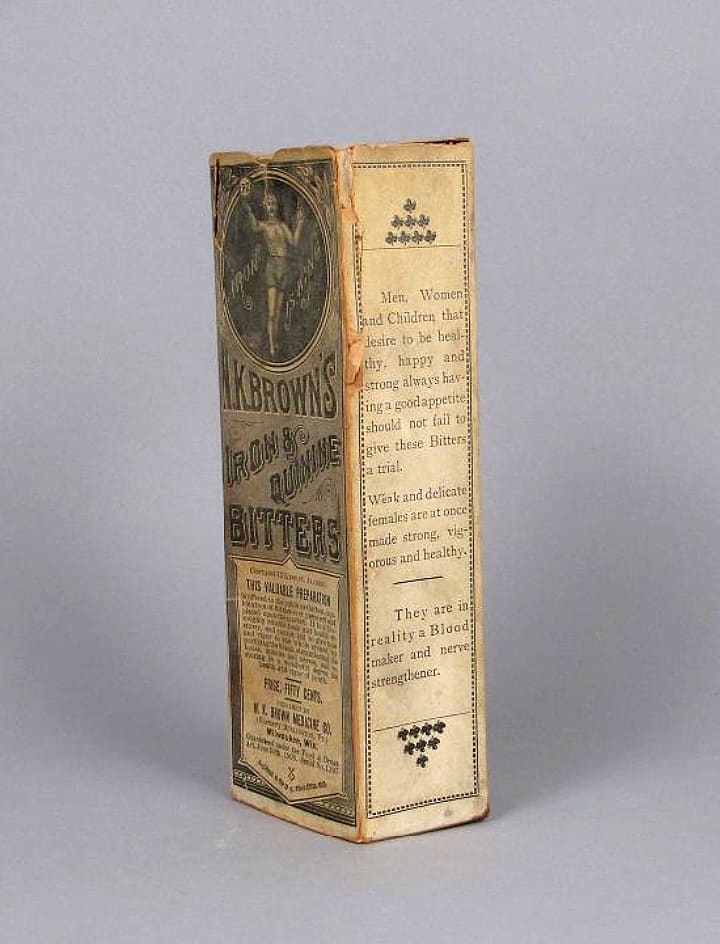

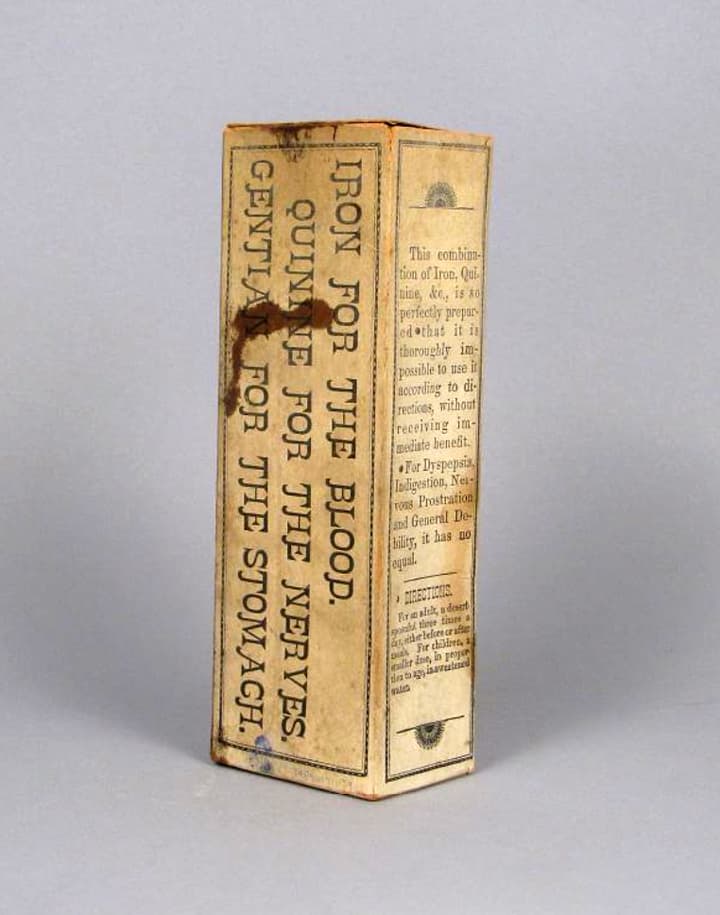

![]() This early bitters for dyspepsia, indigestion, general debility, fever and ague was prepared by N. K. Brown & Co. of Burlington, Vermont. Nathaniel K. Brown was the successor to Fred Smith of Montpelier, Vermont. They produced Smith’s Anodyne Cough Drops with great success. Nathaniel Brown also produced Brown’s Teething Cordial, Star Broches, Bronchial Elixir, Fluid Extract Buchu among others.

This early bitters for dyspepsia, indigestion, general debility, fever and ague was prepared by N. K. Brown & Co. of Burlington, Vermont. Nathaniel K. Brown was the successor to Fred Smith of Montpelier, Vermont. They produced Smith’s Anodyne Cough Drops with great success. Nathaniel Brown also produced Brown’s Teething Cordial, Star Broches, Bronchial Elixir, Fluid Extract Buchu among others.

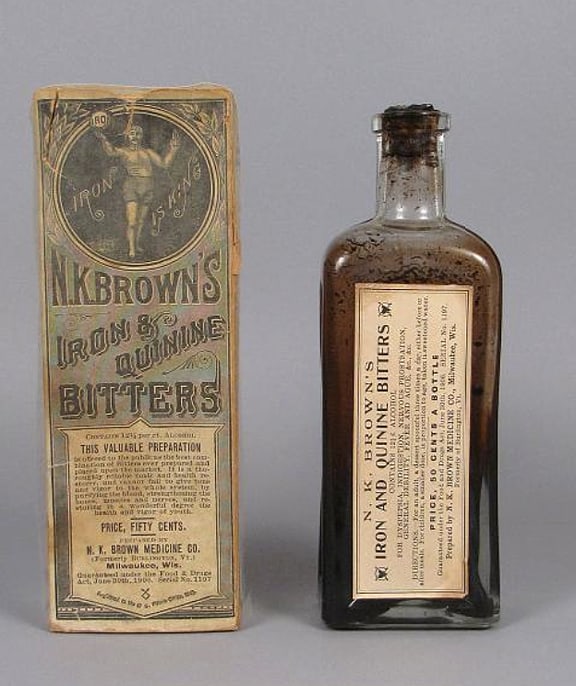

Along with an example from my collection, I was able to locate a great package and fully labeled Iron & Quinine Bitters bottle image from the Smithsonian’s, National Museum of American History, Kenneth E. Behring Center, Gift of Mr. James Harvey Young. These images are positioned further below. The example from my collection is the earlier bottle while the museum example is a later (1910 or so) product by the same company but from Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

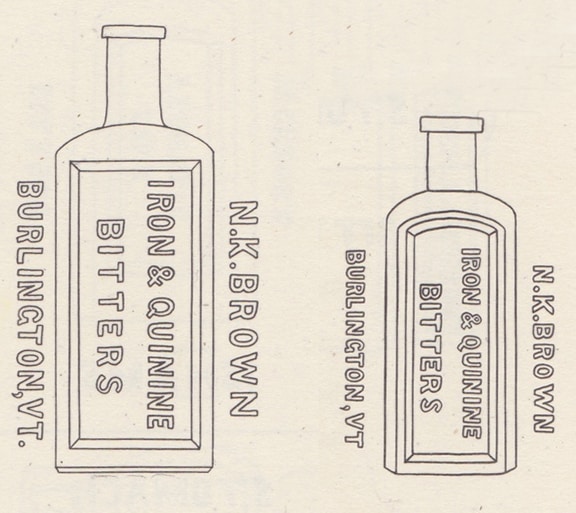

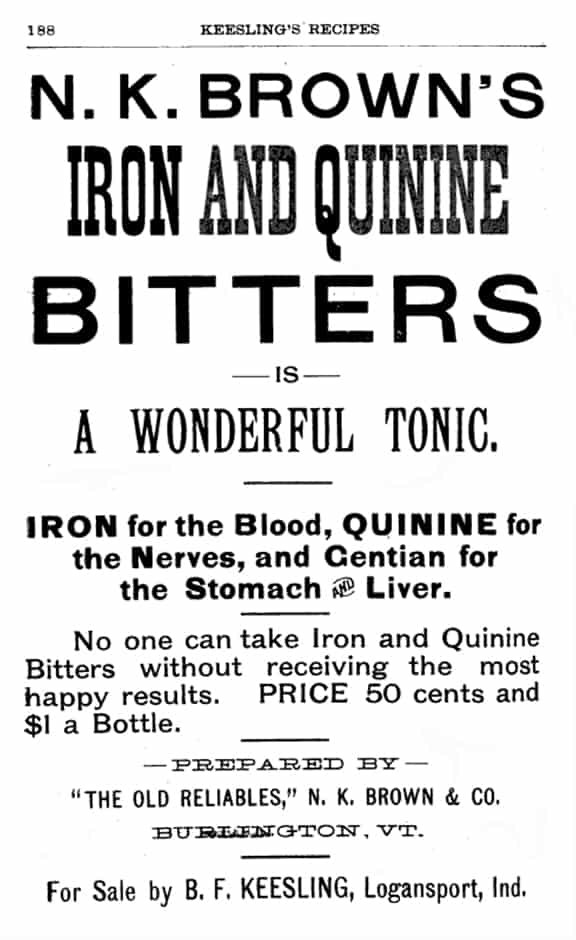

There are two listings in the Carlyn Ring and W.C. Ham Bitters Bottle book:

I 28 IRON & QUININE BITTERS

IRON & QUININE / BITTERS // BURLINGTON, VT // sp // N. K. BROWN //

8 1/2 x 3 x 2 (6 3/8) 1/4

Rectangular, Aqua, NSC, Tooled lip, 4 sp, Rare

Child’s Gazetter Of Crittenden County 1882: Nathaniel K. Brown, 11 South Union Street, The drug catalogues indicate two sizes, 8 oz and 16 oz.

I 29 IRON & QUININE BITTERS

IRON & QUININE / BITTERS // BURLINGTON, VT // sp // N. K. BROWN //

7 1/8 x 2 1/2 x 1 3/4 (5 1/4) 1/8

Rectangular, Aqua and Clear, NSC, Applied mouth and Tooled lip, 4 sp, Rare

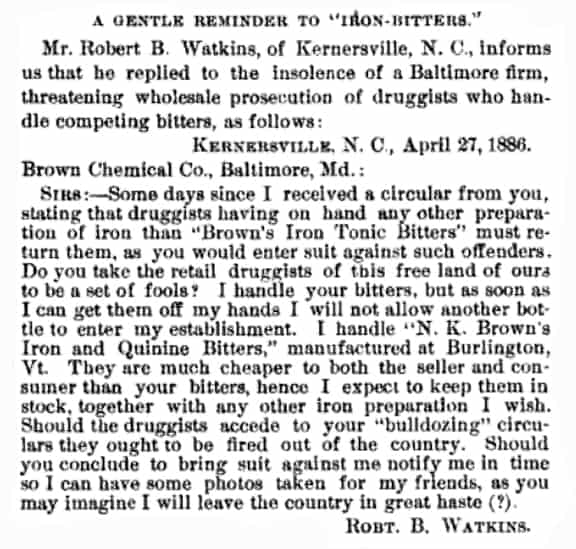

Most bitters collectors will immediately wonder if there is a relationship between this Vermont bitters and the Baltimore, Brown’s Iron Bitters. From the clipping below, you can see there was a problem.

Bound to happen. Brown’s Iron Bitters (Balto) vs. N.K. Brown’s Iron & Quinine Bitters (Burlington) from the Western Druggist, Volume 8 – 1886

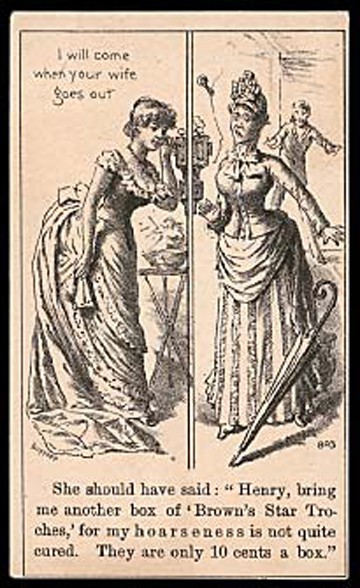

Brown’s Iron & Quinine Bitters – Misdirected Phone Call. Wife accidentally listens to a call from her husband’s girl friend, front advertises Brown’s Star Troches and R-adv is for N. K. Brown’s Iron and Quinine Bitters. F, inked number on reverse.

QUININE

[Wikipedia] Quinine is an effective muscle relaxant, long used by the Quechua, who are indigenous to Peru, to halt shivering due to low temperatures. The Peruvians would mix the ground bark of cinchona trees with sweetened water to offset the bark’s bitter taste, thus producing tonic water.

Quinine has been used in unextracted form by Europeans since at least the early 17th century. It was first used to treat malaria in Rome in 1631. During the 17th century, malaria was endemic to the swamps and marshes surrounding the city of Rome. Malaria was responsible for the deaths of several popes, many cardinals and countless common Roman citizens. Most of the priests trained in Rome had seen malaria victims and were familiar with the shivering brought on by the febrile phase of the disease. The Jesuit brother Agostino Salumbrino (1561–1642), an apothecary by training who lived in Lima, observed the Quechua using the bark of the cinchona tree for that purpose. While its effect in treating malaria (and hence malaria-induced shivering) was unrelated to its effect in controlling shivering from rigors, it was still a successful medicine for malaria. At the first opportunity, Salumbrino sent a small quantity to Rome to test as a malaria treatment. In the years that followed, cinchona bark, known as Jesuit’s bark or Peruvian bark, became one of the most valuable commodities shipped from Peru to Europe. When King Charles II was cured of malaria at the end of the 17th Century with quinine, it became popular in London. It remained the antimalarial drug of choice until the 1940s, when other drugs took over.

The form of quinine most effective in treating malaria was found by Charles Marie de La Condamine in 1737.[6][7] Quinine was isolated and named in 1820 by French researchers Pierre Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Bienaimé Caventou. The name was derived from the original Quechua (Inca) word for the cinchona tree bark, quina or quina-quina, which means “bark of bark” or “holy bark”. Prior to 1820, the bark was first dried, ground to a fine powder, and then mixed into a liquid (commonly wine) which was then drunk. Large-scale use of quinine as a prophylaxis started around 1850.

Quinine also played a significant role in the colonization of Africa by Europeans. Quinine had been said to be the prime reason Africa ceased to be known as the “white man’s grave”. A historian has stated, “it was quinine’s efficacy that gave colonists fresh opportunities to swarm into the Gold Coast, Nigeria and other parts of west Africa”.

To maintain their monopoly on cinchona bark, Peru and surrounding countries began outlawing the export of cinchona seeds and saplings beginning in the early 19th century. The Dutch government persisted in its attempt to smuggle the seeds, and by the 1930s Dutch plantations in Java were producing 22 million pounds of cinchona bark, or 97% of the world’s quinine production. During World War II, Allied powers were cut off from their supply of quinine when the Germans conquered the Netherlands and the Japanese controlled the Philippines and Indonesia. The United States had managed to obtain four million cinchona seeds from the Philippines and began operating cinchona plantations in Costa Rica. Nonetheless, such supplies came too late; tens of thousands of US troops in Africa and the South Pacific died due to the lack of quinine.[9] Despite controlling the supply, the Japanese did not make effective use of quinine, and thousands of Japanese troops in the southwest Pacific died as a result.