Glass House Farm (Glass House Co) 1758 – 1772

Part 3 of a Series

by Stephen Atkinson

10 September 2013

A farm that ran from Fitzroy Road to the Hudson River in what is now the West 30’s in New York City was the site of the last Colonial glass works. It was called The Glass House Farm because of a glass-bottle factory established there in 1758. The factory lasted ten years, but the Glass House Tavern, on the same property, was a popular roadhouse and stage coach stop, up until the Revolutionary War and after.

Around 1800, a small subdivision was laid out, and lots were sold off, in the area roughly bounded by 32nd and 34th Streets between Ninth and Eleventh Avenues. There were three east-west streets named Rapilje, Jersey and Schroepel; and three shorter north-south streets named Moses, Maple and Tulip. The description of the property lists the area still as the Glass House Farm. Refer: Old Streets of New York

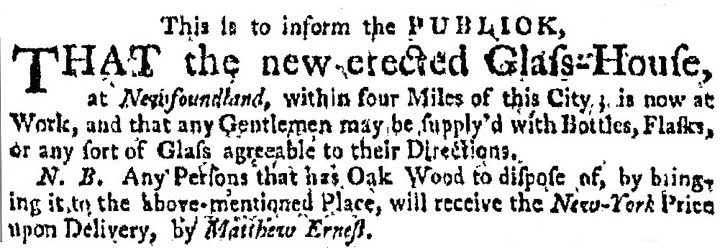

The Glass House Company of New York would build its last glass factory in Newfoundland which is in present day, mid-town New York City which was three miles north of the Glass House Company’s headquarters. We find Matthew Ernest placing an advertisement in the newspaper in the Monday, December 11, 1758 edition of New York Gazette or Weekly Post-Boy. He talks of the newly erected Glas-house.

Advertisement from Matthew Ernest announcing the newly erected Glas-house – Monday, December 11, 1758, New York Gazette or Weekly Post-Boy.

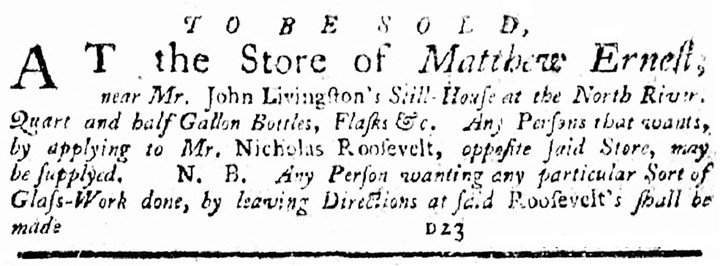

Two weeks later on December 23rd, 1758, the following advertisement was placed in the same paper by Matthew Ernest.

Advertisement from Matthew Ernest announcing “To Be Sold” – Monday, December 23, 1758, New York Gazette or Weekly Post-Boy.

With the year being 1760, these glass works were the only ones left in the New York City vicinity as the Newburgh and Brooklyn enterprises had come to their ends. Unfortunately, one of the founders of the Glass House Company, which oversaw all of these factories, was Samuel Bayard who had passed away in 1758. Matthew Ernests money supply was dwindling and the business mood in general in the Colonies as a whole was not very optimistic. These glass works continued to operate right on up until the start of the American Revolutionary War.

Following the first and largest major engagement of the Continental Army and British troops in the American Revolutionary War, at the Battle of Long Island (also known as the Battle of Brooklyn) on August 27, 1776, General George Washington and the Continental Army retreated to Manhattan Island. The Continentals withdrew north and west and, following the Battle of Fort Washington on November 16, 1776, evacuated the island. For the remainder of the Revolutionary War much of what is now Greater New York and its surroundings were under British control. New York City (then occupying only the southern tip of Manhattan) became, under Lord Howe and his brother Sir William, the British political and military center of operations in North America. David Mathews was the Mayor of New York City during the British occupation.

Correspondingly, the region became central to the development of a Patriot intelligence network, headed by Washington himself. The famous Nathan Hale was but one of Washington’s operatives working in New York, though the others were generally more successful.

The site of the glass factory was north of New York City and was spared some of the horrors of war and it was tough to operate because the North River was being patrolled by the British fleet and shipping and receiving products was difficult at best. Ultimately the war was the most detrimental aspect the factory dealt with and all output ceased when the War of Independence was in full swing. The British were now in control of the city of New York from 1775 through 1776.

The output of this factory did not really differ from the other two works owned by the Glass House Company as all of them made window glass and hollow ware. Glass color again found at the factory site by Fredrick Hunter indicates that dark green glass was used almost exclusively.

With glass blowers from Bristol, England and Germany a very good product line was being turned out. The types of sealed wine bottles in the Van Cortlandt Museum would have been the type still made at this factory. In 1909, workers removing walls and foundation pieces in the old Van Cortlandt home found many sealed F. V. C. 1765 tall wine bottles along with bottles similar in shape but void of the seals. All of these bottles are now preserved in the Van Cortlandt Museum. The works were abandoned during the war as the British were in control of the city.

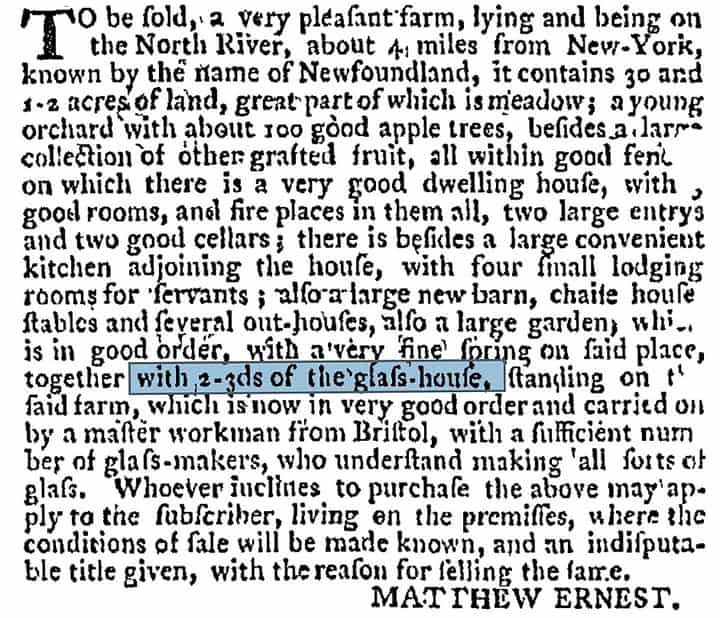

In the Monday, March 23, 1761 edition of the New York Mercury, Matthew Ernest lists the following long advertisement and he must have sub-divided the property prior, for he lists as for sale, only two thirds of the Glass House. He does state that the works is being operated by a gentleman from Bristol, England with a large work force suggesting the factory was in good operation and that he was probably still selling their wares.

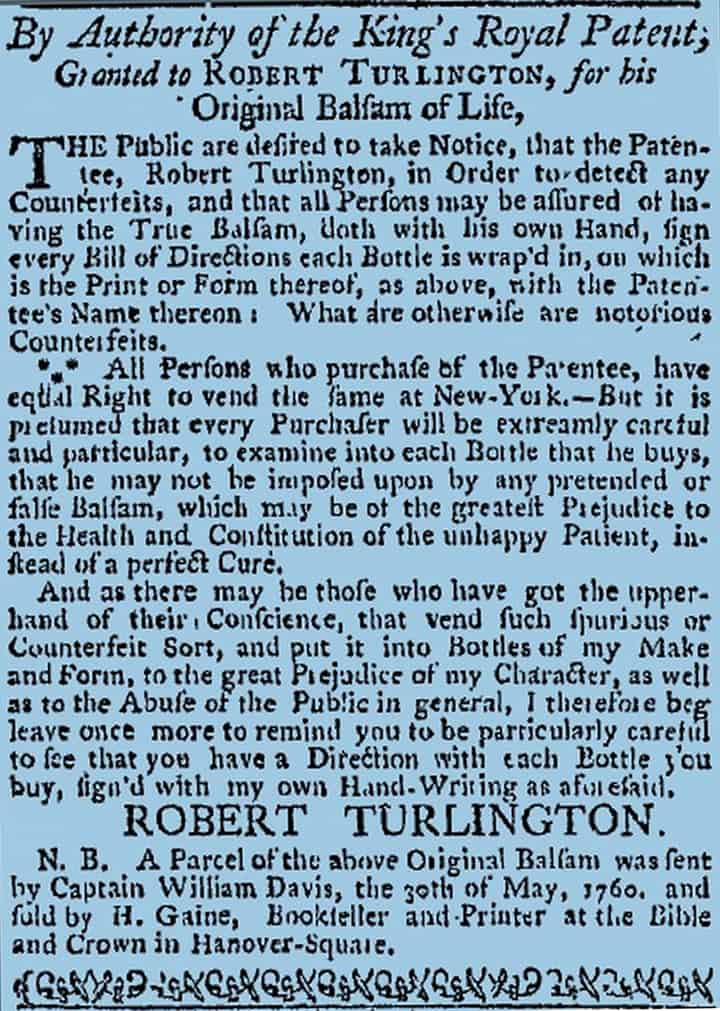

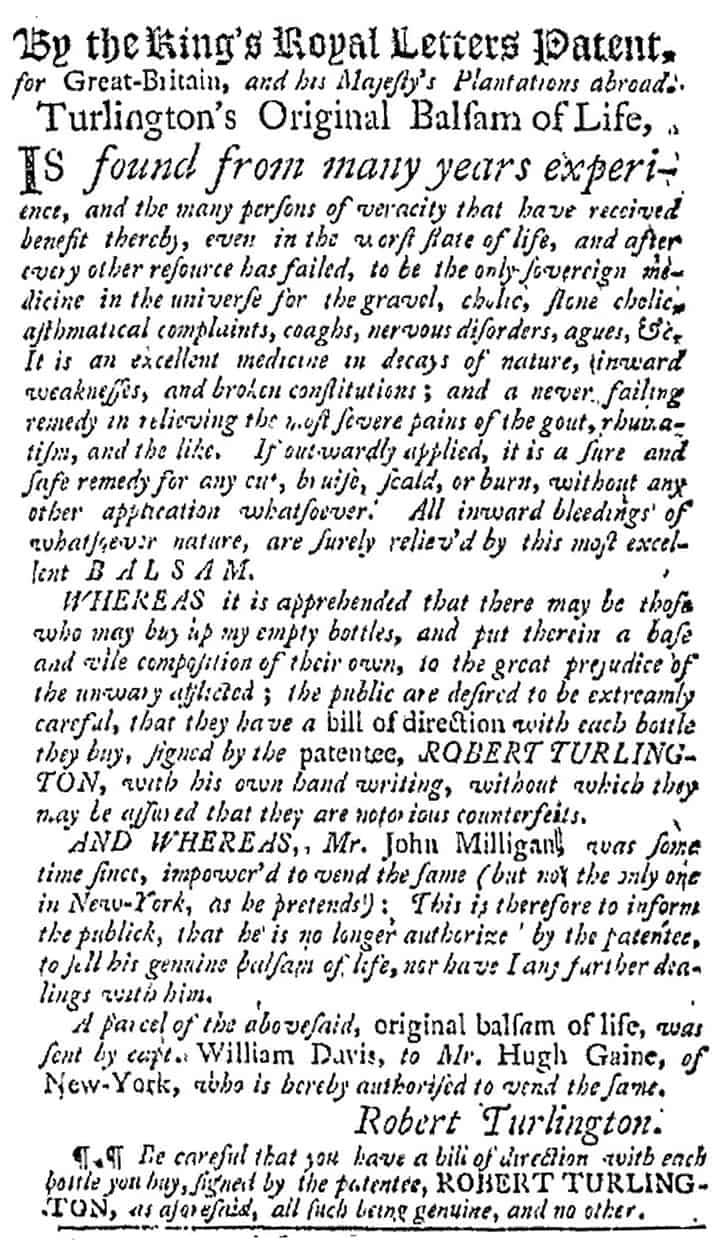

Robert Turlington was advertising quite heavily in New York and Philadelphia newspapers in the late 1750s right through the start of the Revolutionary War. No other nostrum was as counterfeited as Turlington’s Balsam Of Life because Robert was in a constant battle with the agents he hired to sell his medicine in the two cities. A quite likely source of the imitation bottles being sold, that Robert shares with the reader in the New York market, was most likely the Glass House Farm and a gentleman who had dealings with them in the past. They were also just 3 – 1/2 miles to the north and were in business during the time period the counterfeiting began.

I strongly believe that some of the pale green, aqua colored versions of this bottle which appear from time to time pontiled and quite crude, were the earliest attempts of counterfeiting in the 1760 to 1790 time period. All made by workers at the Glass House Farm who had emigrated from the Bristol, England area and who had worked in the glass industry while living there. This was big business and Robert Turlington was hiring and firing agents every few years. Here are a series of notices from New York City newspapers showing the great concern Robert Turlington had for his product.

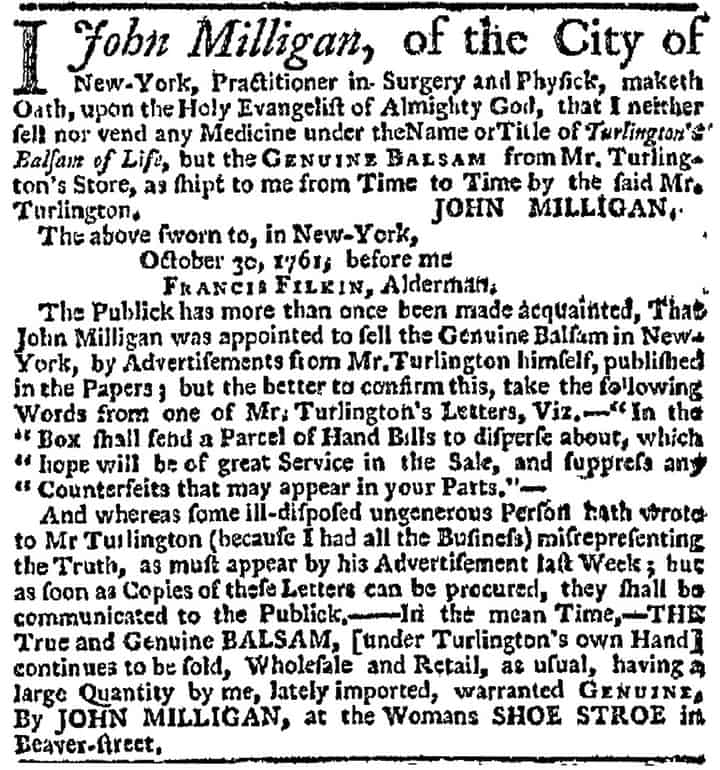

In the Monday, November 2, 1761 edition of the New-York Mercury newspaper (New York, NY) we find Turlington denouncing Mr. John Milligan who had sold the medicine for Robert Turlington for the past five years. Milligan was accused of selling refilled original bottles and counterfeit ones by Turlington and was no longer considered an agent for the product. Turlington was now including a large paper wrapper around each bottle stating the contents and originality of the product in the bottle. Without this paper, with Turlingtons signature on it, a bottle was considered counterfeit and should be avoided by the consumer.

On the same day he was accused and banned from selling the Turlington Balsam, John Milligan placed an advertisement in the Monday, November 2, 1761 edition of the New-York Gazette (New York, NY) and stated his side of the accusation of impropriety leveled by Robert Turlington. Milligan was not going to go away easily and continued to sell the product at his store even though Robert Turlington forbade him to do so.

John Milligan placed an advertisement in the Monday, November 2, 1761 edition of the New-York Gazette stating his side of the accusation of impropriety leveled by Robert Turlington.

Here are some of the type of Turlington bottles that may have been made at the Glass House Farm and sold to the public as original medicine imported from England. Most of these were found in the Philadelphia – South Jersey area but I am using these as a reference as to what the imposters may have looked like.

Robert Turlington Balsam bottles from the late 1700s aqua in color and made very crudely. The long neck version is unique, and I have never seen another like it.

Robert Turlington Balsam bottle. The long necked version close-up from above. Green striations of color in the glass near the lip.

Group shot of four Turlington Balsam of Life bottles. The one on the far right is a British made original example from the mid 1700s.

The British ‘Turlington Balsam of Life” example in close has a silvery greyish cast to the clear flint glass.

About Stephen Atkinson

Stephen Atkinson, from Sewell, New Jersey has been collecting bottles and glass since he was 12 years old. He once dug an original EG Booz figural cabin bottle on Norris Street in Mantua, New Jersey in 1972 at 12 years old and traded it for six bitters bottles. Fast forward to 2012 and Stephen bought the exact bottle back at an estate auction in New Jersey!

His passion is for pre-1880 glass, as the majority of his collection consists of historical flasks, colonial era chestnut bottles, and whimsical end of day pieces of glass. He also has three rare T.W. Dyott bottles, an original Dr. Robertson’s family medicine; one of the rarest collectable American bottles, a T.W. Dyott vial bottle dug by Chris Rowell and a paper labeled T.W. Dyott bottle. He has researched many southern New Jersey glass works first hand by locating the original factory sites. The best piece in his collection is the Wistarburgh Glass Company ledger showing monies paid out to Caspar Wistar’s Children and their husbands and wives.

Read more in this series by Stephen Atkinson:

The New York State Glass Factories | Preface to a Series

Newburgh (Glass House Co.) 1751-1759 | Part 1

Brooklyn (Glass House Co.) 1754-1758 | Part 2

Ferd: These articles on early American glass houses are fascinating. I don’t know if Stephen is a trained archeologist or researcher but this is what archeologists should be doing. I see the best information and exhibition coming from glass collectors. It makes me wonder just who is the best preserver of history. No I guess I don’t really wonder I know collectors have published the most books and articles and are really the greatest historians. MAX BELL

PS publish this as a comment on the glass houses if you wish I cannot remember my password.