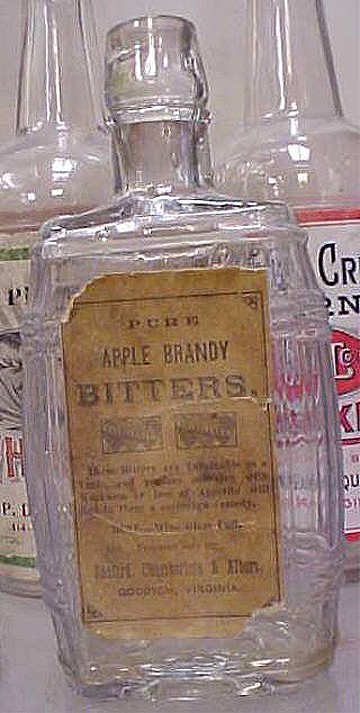

Two labeled, Pure Apple Brandy Bitters – Knoxville, Tennessee & Goodson, Virginia

Pure Apple Brandy Bitters

Sanford, Chamberlain & Albers

14 October 2013

![]() Last week, you may remember a post I developed on the unlisted Betterton Bitters from Knoxville, Tennessee. Read: The Betterton Bitters brands – Knoxville, Tennessee. One of the bottles was the Betterton’s Celebrated Apple Brandy Bitters. While I was working in this area I also came across a labeled, Pure Apple Brandy Bitters put out by Sanford, Chamberlain & Albers in Knoxville. This bitters is listed in Ring & Ham. These bottles were on Charlie Barnette’s wonderful web site, Bristol, Tenn-Va Collectible Bottles & History. As it turns out, there is a wealth of interesting information regarding this brand and the proprietors. I also wanted to make note that the label is applied to a figural barrel bottle if you had not noticed.

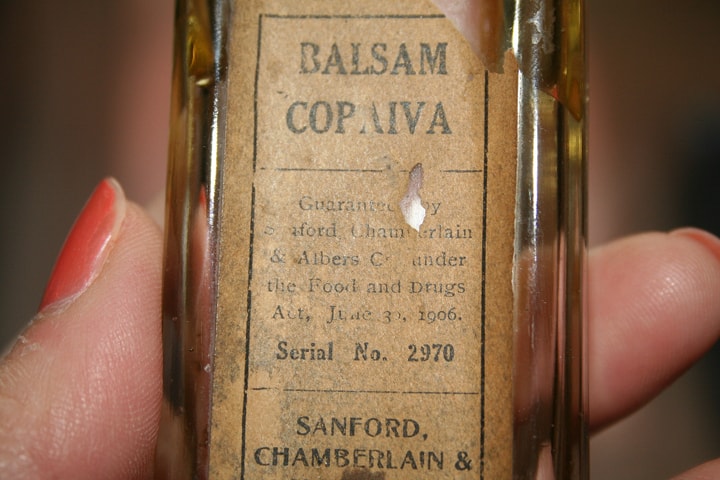

Last week, you may remember a post I developed on the unlisted Betterton Bitters from Knoxville, Tennessee. Read: The Betterton Bitters brands – Knoxville, Tennessee. One of the bottles was the Betterton’s Celebrated Apple Brandy Bitters. While I was working in this area I also came across a labeled, Pure Apple Brandy Bitters put out by Sanford, Chamberlain & Albers in Knoxville. This bitters is listed in Ring & Ham. These bottles were on Charlie Barnette’s wonderful web site, Bristol, Tenn-Va Collectible Bottles & History. As it turns out, there is a wealth of interesting information regarding this brand and the proprietors. I also wanted to make note that the label is applied to a figural barrel bottle if you had not noticed.

The Carlyn Ring and Bill Ham listing in Bitters Bottles Supplement is as follows:

A 79.7 L … Pure Apple Brandy Bitters, Sanford, Chamberlain & Albers, Goodson, Virginia (should be Knoxville, Tennessee first)

Label on an unembossed clear whiskey barrel figural.

Similar label on bottle: Prepared only by Sanford, Chamberlane & Albers, Knoxville, T. , Jan 29, 1860

The Knoxville drug firm Sanford, Chamberlain & Albers was founded in 1872. Edward Jackson Sanford, who moved to Knoxville from Connecticut in 1853, worked as a carpenter, contractor and partner in a lumber firm prior to the Civil War.

Sanford, Chamberlain, and Albers would serve as a vibrant part of Knoxville’s business community for one hundred years.

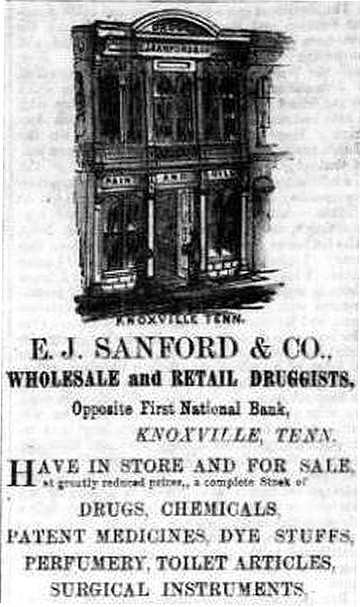

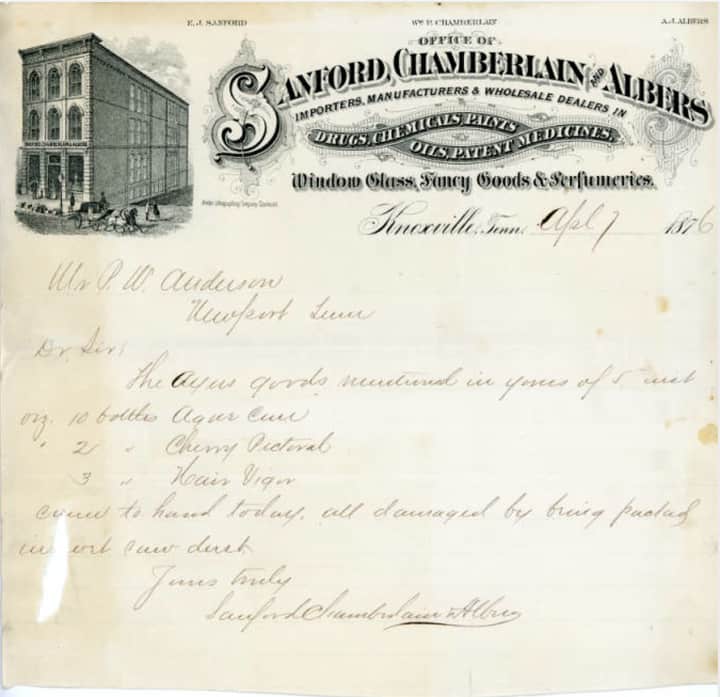

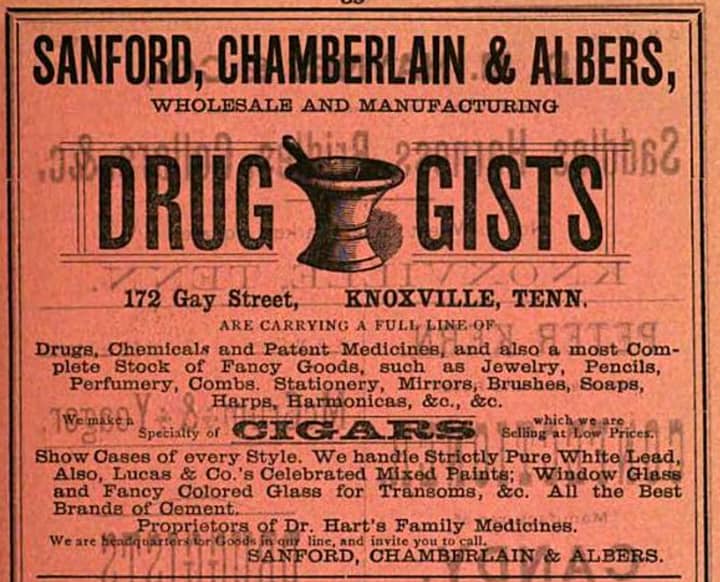

When Confederates seized Knoxville, Sanford and his wife, Emma Chavannes fled to Kentucky to join the Union Army. Rejected from service due to an illness, Sanford and his wife spent a few years in Connecticut before returning to Knoxville after Union forces under General Ambrose Burnside had captured the city. In Knoxville, Sanford joined the Union Army and fought in the Battle of Fort Sanders. As a result of the war, Sanford extended his business interests and organized the drug firm of E. J. Sanford and Company in 1864 (see advertisement above). Sanford quickly became a wealthy and influential citizen of Knoxville. In 1872, he saw an opportunity to increase his business by merging his firm with the Albers and Chamberlain Drug Company (see advertisement below). The new company changed its name to Sanford, Chamberlain, and Albers and became one of the leading drug companies in the industry. Sanford, Chamberlain, and Albers would serve as a vibrant part of Knoxville’s business community for one hundred years. The company’s name was shortened to Alber’s Drug Company in 1926 and remained in the hands of the Albers family until 1994 when it was sold to the Walker Drug Company in Birmingham, Alabama.

Advertisement for the Sanford, Chamberlain and Albers Drug Company in the Knoxville, Tennessee, Norwood’s Knoxville Directory of 1884.

Edward Jackson Sanford (November 23, 1831 – October 27, 1902) was an American manufacturing tycoon and financier, active primarily in Knoxville, Tennessee, in the late 19th century. As president or vice president of two banks and more than a half-dozen companies, Sanford helped finance Knoxville’s post-Civil War industrial boom, and was involved in nearly every major industry operating in the city during this period. Companies he led during his career included Sanford, Chamberlain and Albers, Mechanics’ National Bank, Knoxville Woolen Mills, and the Coal Creek Coal Mining and Manufacturing Company.

Edward Jackson Sanford (November 23, 1831 – October 27, 1902) was an American manufacturing tycoon and financier, active primarily in Knoxville, Tennessee, in the late 19th century. As president or vice president of two banks and more than a half-dozen companies, Sanford helped finance Knoxville’s post-Civil War industrial boom, and was involved in nearly every major industry operating in the city during this period. Companies he led during his career included Sanford, Chamberlain and Albers, Mechanics’ National Bank, Knoxville Woolen Mills, and the Coal Creek Coal Mining and Manufacturing Company.

Sanford was born in Fairfield County, Connecticut, in 1831. He was trained as a carpenter, and moved to Knoxville at the age of 22 to work in this trade. He initially worked for Shepard, Leeds and Hoyts, which built railroad cars. Later in the decade, he cofounded a lumber and construction company. Although many people fled Knoxville during the city’s cholera outbreak of 1854, Sanford stayed behind to help care for the sick and dying.

At the outset of the Civil War in November 1861, Sanford helped fellow Unionist William Rule sneak out of Confederate-occupied Knoxville to carry messages to newspaper editor William G. Brownlow, who was in hiding in the mountains. In 1862, Sanford fled to Kentucky to join the Union Army, but fell ill before he could enlist (Sanford’s account of his escape to Kentucky was later published as an appendix in Thomas William Humes’s The Loyal Mountaineers of Tennessee). He returned to Knoxville following Burnside’s capture of the city in late 1863. Sanford fought at the Battle of Fort Sanders on November 29, 1863, and years later, provided historian Oliver Perry Temple with an account of the battle for Temple’s book, East Tennessee and the Civil War.

Toward the end of the war in 1864, Sanford formed a drug company, E. J. Sanford and Company. In 1872, this firm consolidated with Chamberlain and Albers, which had been established by Knoxville businessmen Hiram Chamberlain and A. J. Albers, to form Sanford, Chamberlain and Albers. In subsequent years, this new company grew to become one of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the South.

During the late 1860s, Sanford helped establish the Coal Creek Mining and Manufacturing Company, which purchased over 60,000 acres of land in the coal-rich Coal Creek Valley of western Anderson County. This company in turn leased the land to various mining firms, most notably the Knoxville Iron Company and the Tennessee Coal Mining Company (TCMC). In 1891, an uprising known as the Coal Creek War erupted when the latter attempted to replace its free miners with convict laborers. While Sanford blamed a “fool contract” made by TCMC president B.A. Jenkins for the uprising, he nevertheless supported the use of convict labor as a means to keep regional coal companies competitive.

In 1882, Sanford helped organize the Mechanics’ National Bank, and initially served as the bank’s vice president. In October of that same year, however, the bank’s first president, Thomas O’Connor, was killed in a notorious shootout in Downtown Knoxville. Sanford served as an interim president until Samuel B. Luttrell was elected president of the bank in 1883.

During the late 1880s, Sanford became enamored with social theories regarding the development of planned cities, where company workers could live free from the vices that plagued large cities. In 1889, he and his long-time associate, Charles McClung McGhee, founded the Lenoir City Company with plans to establish such a town. The company purchased the Lenoir estate in Loudon County and platted what is now Lenoir City in 1890. While the Panic of 1893 seriously stunted the new city’s growth, the city survived, and today, part of the city still follows the Lenoir City Company’s early-1890s grid.

During the 1880s and 1890s, Sanford served as president of the Knoxville Woolen Mills, which under his leadership had grown to become Knoxville’s largest textile firm by 1900. During this same period, he served as a director of several other companies, including the East Tennessee, Virginia and Georgia Railway, the Knoxville Brick Company, and the Knoxville Iron Company. In 1898, Sanford purchased both the Knoxville Journal and the Knoxville Tribune, and combined the two into a single newspaper. He retained his old Civil War-era associate, William Rule, as the paper’s editor.

Sanford died at his home in Knoxville on October 27, 1902. He is interred in Old Gray Cemetery. The company he cofounded, Sanford, Chamberlain and Albers, continued operating in Knoxville as Albers, Inc., until 1994. The company’s former store and office at 430 South Gay Street still stands, and is a contributing property in the National Register of Historic Places-listed Gay Street Commercial Historic District. Maplehurst Park, an apartment complex in Downtown Knoxville, is named for Sanford’s mansion, Maplehurst, which once stood on the property.

Sanford was a lifelong advocate for education in Knoxville. In 1869, working as an agent for East Tennessee University (now the University of Tennessee), he helped secure for the institution the state’s Morrill Act (land-grant) funds. During the same period, he advocated the establishment of a public school system in Knoxville, and served as the president of the city’s Board of Education in the early 1880s.

Persons in the photo: Edward J. and Emma (Chavannes) Sanford and family, August 1886. From left: Mary (Sanford) Ault, Edward J. Sanford, Emma (Sanford) Sanford Robinson, Emma (Chavannes) Sanford, Edward T. Sanford and Alfred F. Sanford. Seated on the floor: Louise (Sanford) Fisher, and Hugh W. Sanford.

This photo and discription of persons in the photo is found in the book by David Babelay, They Trusted and Were Delivered, The French-Swiss of Knoxville, Tennessee. Pub 1988.

Sanford’s son, Edward Terry Sanford (1865–1930), was a prominent Knoxville attorney who served as an associate justice on the United States Supreme Court from 1923 until 1930. Another son, Alfred (1875–1946), continued publishing the Knoxville Journal until 1928, when he sold the paper to senator and publisher, Luke Lea. Sanford’s son, Hugh (1879–1961), was a Knoxville-area iron manufacturer who advised the War Industries Board and the Council of National Defense during World War I. [Wikipedia]

Pure Apple Brandy Bitters, Knoxville, Tennessee [Collection of Ralph Van Brocklin] – purchased at Yankee Bottle Show in Keene, New Hampshire

GOODSON, VIRGINIA…Where’s That? – Charlie Barnette

From: BRISTOL, TENN-VA COLLECTIBLE BOTTLES & HISTORY

When Joseph R. Anderson purchased the King’s Meadows property from his father-in-law in 1852, the parcel was found to extend into both Tennessee and Virginia. After he named his town Bristol, and began laying off streets and lots, there came into existence both a Bristol ,Virginina and a Bristol, Tennessee.

Adjoining his parcel on the northeast in Virginia was land owned by Col. Samuel Goodson, who also began to lay off streets and lots and, who named his town Goodsonville (about 1852-53). In December of 1855, a meeting was held by its citizens to incorporate Goodsonville and Anderson’s Bristol, Virginia into one town, to be named Goodson. This incorporation was granted in March of 1856.

From the beginning, Goodson had an identity problem. All through its 34 years of existence it was known as Bristol (research indicates even Goodsonville had the same problem). After the incorporation, many businesses continued to to give their locations as Bristol, Virginia. Newspapers, contracts, business cards, some deeds, even the official records of the Confederacy gave the location as Bristol. There are numerous papers showing the double identity, such as Bristol-Goodson or Goodson-Bristol, when locations were on the Virginia side of town. Occasionally one may find such addresses as “Bristol – north of Main Street” or “the Virginia side of Bristol.”

Adding to it all was the fact that the railroad flatly refused to recognize Goodson and continued to give its depot location as Bristol, Virginia. There are many stories of the confusion and difficulty encountered by people during this time. One story has a perplexed wholesaler stating he sold a bill of goods to a merchant who said he was doing business in Goodson, Virginia, but the goods had been sent to Bristol, Virginia, and the man gave his address as Bristol, Tennessee! This type of problem and confusion continued until 1890, when the town took back the original name of Bristol, Virginia.

Goodson, Virginia, Pure Apple Brandy Bitters was sold on eBay. (Nov.2005) The label is in much better condition than the previously known example’s. [Collection of Ralph Van Brocklin]

Embossed Knoxville, Tennessee bottles from E. J.Sanford & Co., Albers & Co., as well as those from Sanford, Chamberlain & Albers have been dug in Bristol and its environs. The Goodson, Virginia store must have been an outlet they began here in an attempt to make their products more known. When established and for how long is not known by me. Also, why they chose to place Goodson, Virginia on their labels doesn’t make sense, given the difficulty and confusion surrounding Goodson’s identity crisis during its existence. – Charlie Barnette