More on the Color Orange in Antique Glass

by Ken Previtali

09 February 2014

By the way, the word orange is one of the few words in the English language for which there is no effective rhyme.

By the way, the word orange is one of the few words in the English language for which there is no effective rhyme.

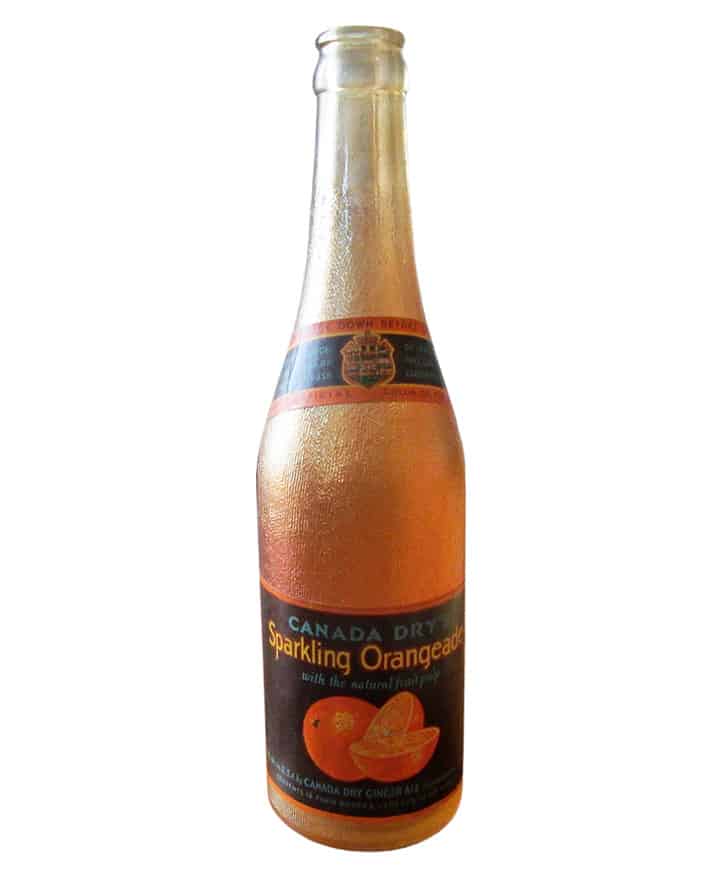

What is interesting about the Canada Dry Sparkling Orangeade bottle (pictured above) is that the color is not in the glass. When you look up through the bottom of the bottle it is clear. The color and iridescence are on the surface. That makes me think of stained glass. When it comes to stained glass, orange is more of a modern color. There is not much use of it in very early windows, where color glazes were painted on the glass and re-fired. It’s possible that the color was not easily made until the 19th century. Some Victorian windows used orange, but not many (see below).

Richly colored Sun motif made of a variety of cathedral glass. – Age of Elogance

Tiffany created his range of orange colors by adding silver nitrate and other metal salts to a batch of red glass (see below).

Louis Comfort Tiffany stained glass window – Metropolitan Museum of Art

What was the fascination with oranges (and perhaps the color)? According to John McPhee, in his marvelous book Oranges, the fruit made its way from southern China to India, where the word orange evolved from the Sanskrit language some 2,000 years ago. McPhee says:

“The modern use of lemon and orange peels in alcoholic drinks has ample precedents in many places and centuries, but the custom perhaps reached its highest point in Holland three hundred years ago. The drinking Dutch, in the 17th century, would peel a helical ribbon of skin from an orange, continuing round and round until the knife reached the fruit’s equator. Then, with the ribbon still attached, they would place the entire orange, like a huge Martini olive, in the bottom of what might have been described as an elegant bucket. Dutch fondness for the combination of oranges and wine eventually led to the invention of bitters– or at least the commercialization of bitters, for even the ancient Chinese had known the special excellence of Bitter Oranges with wine. Dutch bitters were a concentrated essence usually made by marinating dried Bitter Orange peels in gin. The still-lifes of Dutch and Flemish masters often show oranges beside bottles of wine.”

Oranges by John McPhee, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966.

Here’s an example of a Dutch painting (see above) by Jan Jansz van de Velde III (c. 1620-1662). I’m not sure what “elegant bucket” McPhee means, but in this painting the glass is a roemer. The British Museum describes a roemer as “a type of drinking glass used for wine, made from green waldglas (forest glass). This stem is decorated with raspberry prunts, applied blobs of glass stamped with fireproof clay or metal to form a pattern. The prunts served a functional use as well as a decorative purpose: during a meal they provided a grip for greasy hands, important at a time when forks were not commonly used. The foot is made from a single thread of glass spun around a wooden conical form. Roemers were made in quantity in the many German forest glasshouses during the seventeenth century, and were exported throughout Europe. Roemers were also made in quantity in the Low Countries. Many can be seen in Dutch seventeenth-century still-life paintings.”

Engraved glass (roemer) – The British Museum

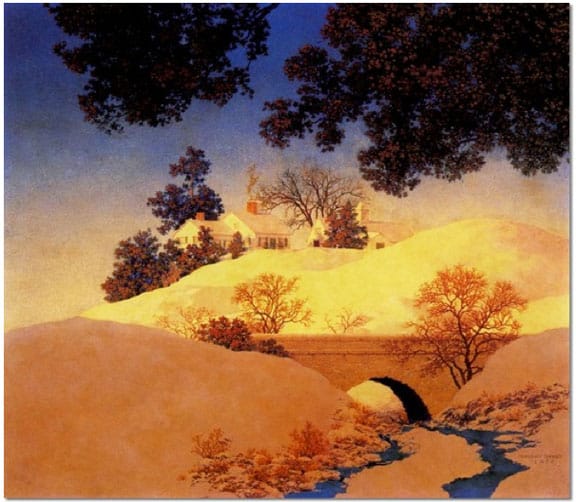

Maxfield Parrish (1870-1966) also appeared to love orange. Many of his paintings fairly dripped with glowing orange. Parrish is one of the most widely reproduced American artists. Could it be the “orange attraction”? By the way, the word orange is one of the few words in the English language for which there is no effective rhyme.

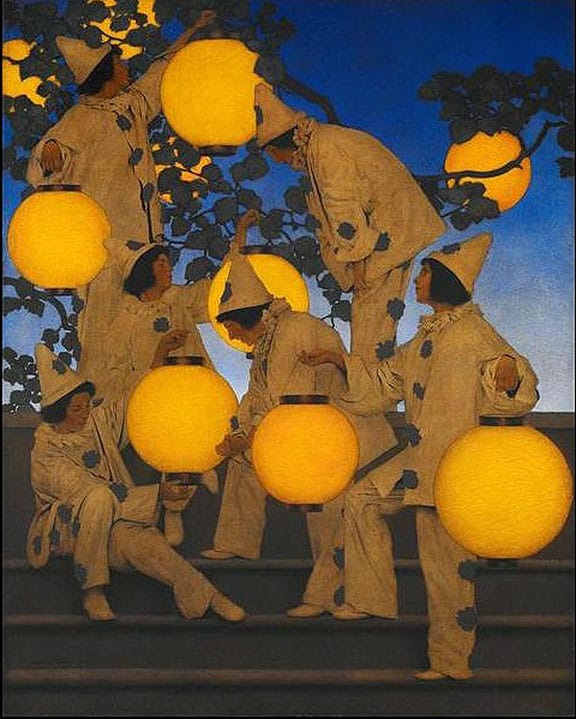

The Lantern Bearers, 1908, oil on canvas on board, created for Collier’s magazine, the painting shows Parrish’s use of glazes and saturated color in an evocative night scene – Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

Read More: The Color Orange in Antique Bottles & Glass