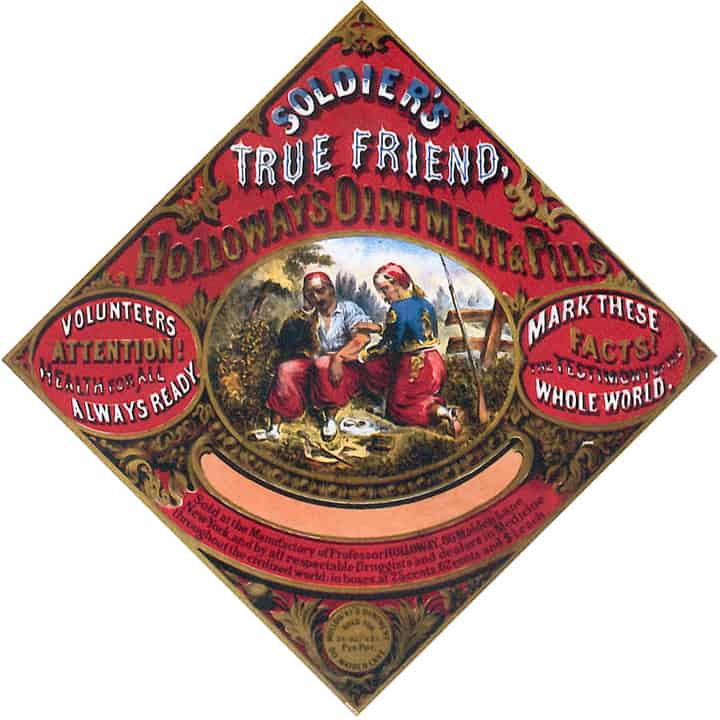

Soldier’s True Friend, Holloway’s Ointment & Pills

For Wounds either occasioned by the Bayonet, Sabre or the Bullet, Sores or Bruises.

14 April 2014

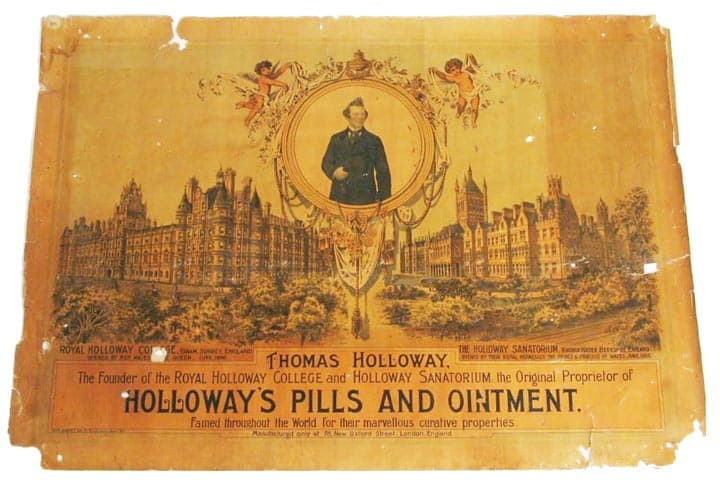

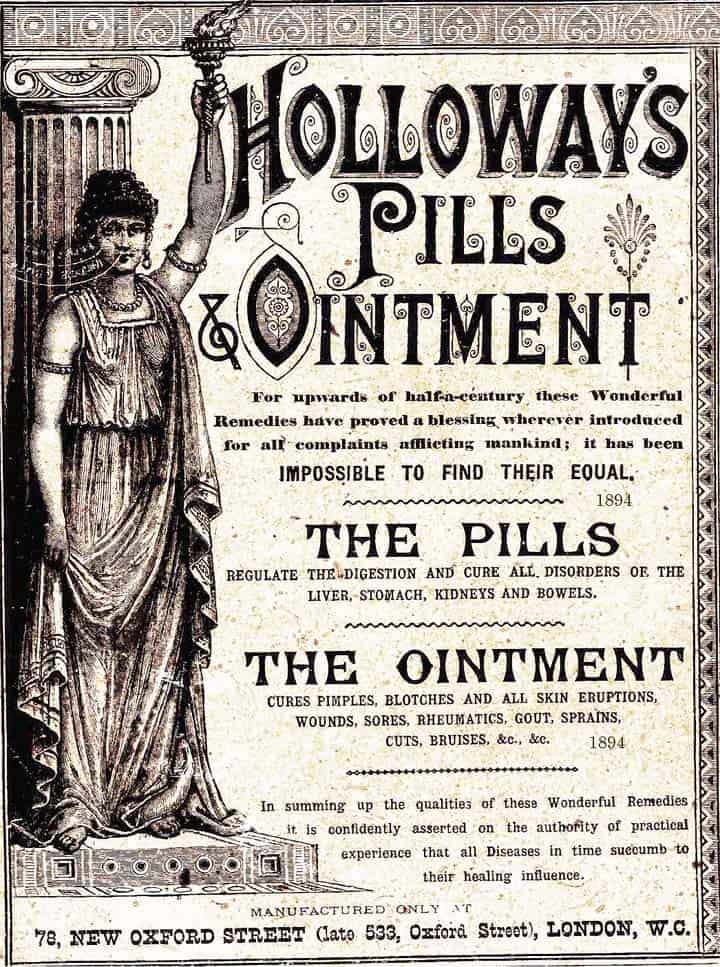

Poster, “Holloway’s Pills and Ointments”, paper, printed by John Harrar & Son, London, part of shop fittings, Wong family, Australia, 1880-1930

![]() I could not help but to get side tracked with George W. Holloway, the Syracuse Druggist, yesterday with another Holloway, that being Thomas Holloway who was born in September 1800 and was a patent medicine vendor and philanthropist from England. His pills and ointments were sold around the world. His claims were outlandish and his products were most likely, not much help.

I could not help but to get side tracked with George W. Holloway, the Syracuse Druggist, yesterday with another Holloway, that being Thomas Holloway who was born in September 1800 and was a patent medicine vendor and philanthropist from England. His pills and ointments were sold around the world. His claims were outlandish and his products were most likely, not much help.

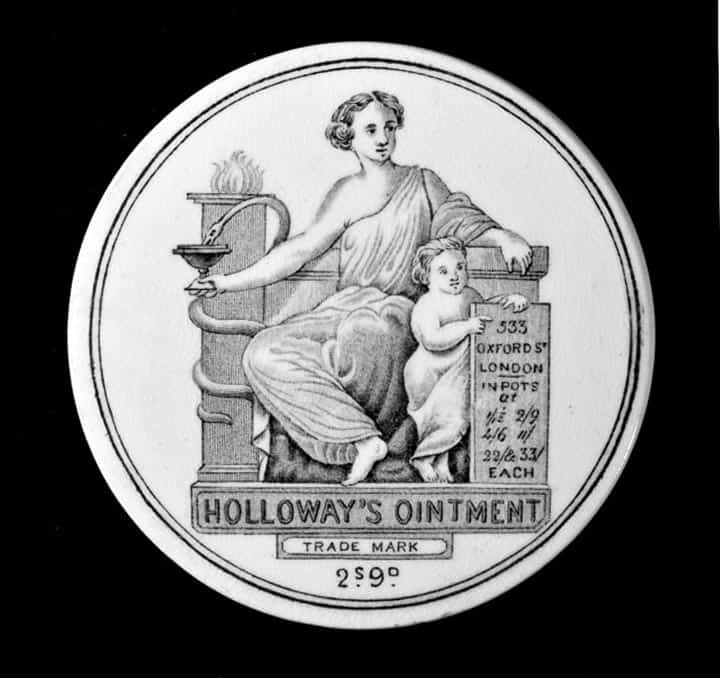

Read: Victorian Ointment Pots

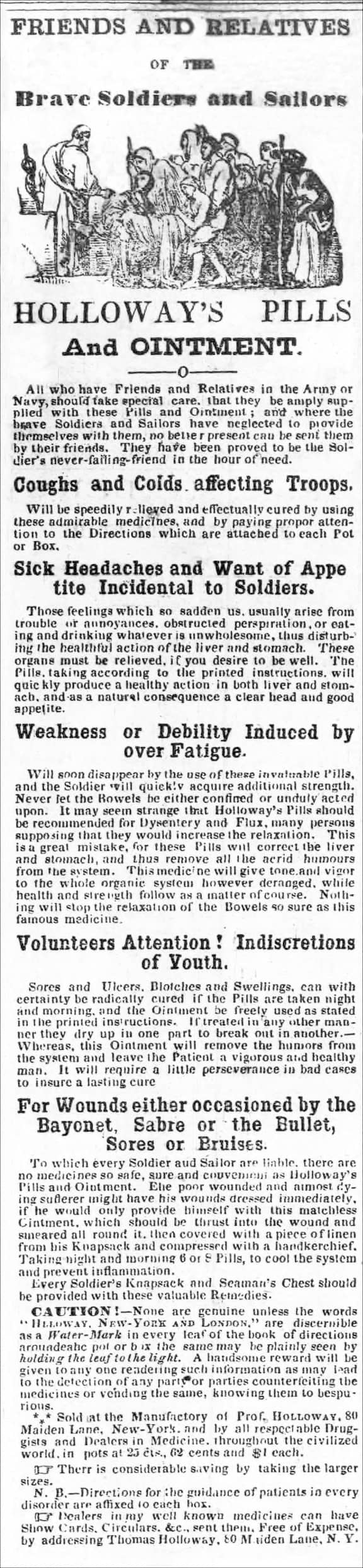

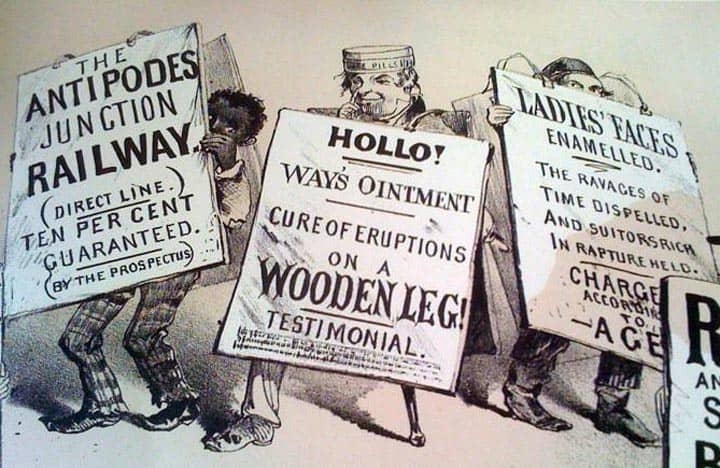

What surprised me was the abundance of material on Thomas Holloway. I found lots of historical posts on the man, his ointments, pots and lids, advertising and postal history. One 1863 New York newspaper advertisement (below), seems to best represent the claims and strategy for marketing Holloway’s Pills and Ointments. He seemed to direct many of his messages to “Friends and Relatives of the Brave Soldiers and Sailors”. Stateside, he set up shop at 80 Maiden Lane in New York.

Thomas Holloway

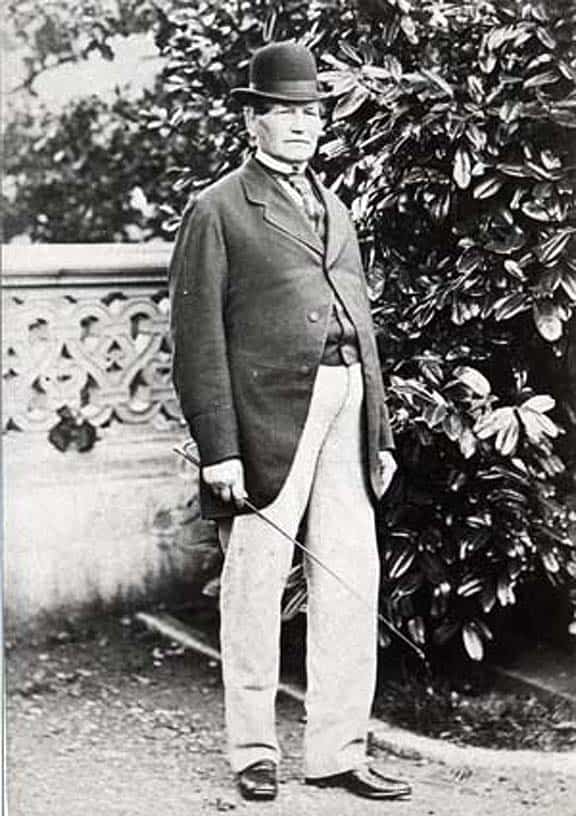

Thomas Holloway (22 September 1800 – 26 December 1883) was a patent medicine vendor and philanthropist from England.

Holloway was born in Devonport, a district of Plymouth in the county of Devon, the eldest son of Thomas and Mary Holloway (née Chellew), who at the time of their son’s birth had a bakery business. They later moved to Penzance, Cornwall, where they ran The Turk’s Head Inn. In the late 1820s, Holloway went to live in Roubaix, France, for a few years. He returned to England in 1831 and worked in London as a secretary and interpreter for a firm of importers and exporters. In 1836, he set himself up as a foreign and commercial agent in London.

Holloway had business connections with an Italian, Felix Albinolo, who manufactured and sold a general purpose ointment. This gave Holloway the idea to set up a similar business himself in 1837. He began by using his mother’s pots and pans to manufacture his ointment in the family kitchen. Seeing the potential in patent medicines, Holloway soon added pills to his range of products. Holloway’s business was extremely successful.

During the mid 1850’s, he employed an agent in the United States (as evidenced from some advertising in the New York Daily Times dated September 1852), to market pills and his ointment. Further evidence from advertising recorded in the same journal in March 1855 proves that Holloway’s business in the US was well established and that his business was trading from an address known as 80 Maiden Lane New York, In 1878 the business moved a few doors along to 78 Maiden Lane, New York.

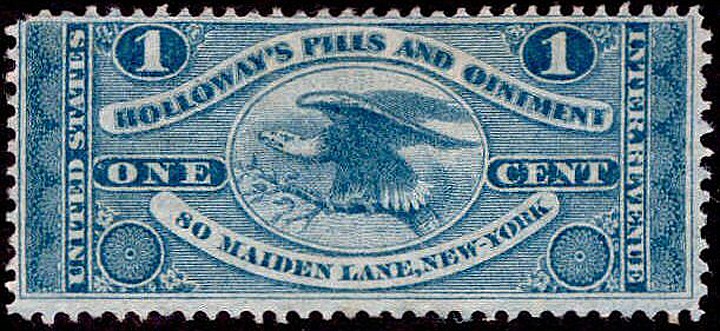

Holloway’s Pills and Ointments, 80 Maiden Lane Private Die Stamp – rdhinstl.com

A key factor in his enormous success in business was advertising, in which Holloway had great faith. Holloway’s first newspaper announcements appeared in 1837, and by 1842 his yearly expenses for publicity had reached over £5,000 (GBP). By the time of his death, he was spending over £50,000 a year on advertising his products. The sales of his products made Holloway a multi-millionaire, and one of the richest men in Britain at the time. Holloway’s products were said to be able to cure a whole host of ailments, though scientific evaluation of them after his death showed that few of them contained any ingredients which would be considered to be of significant medicinal value. Holloway’s medicine business slowly declined and was bought by rival Beecham’s Pills in 1930.

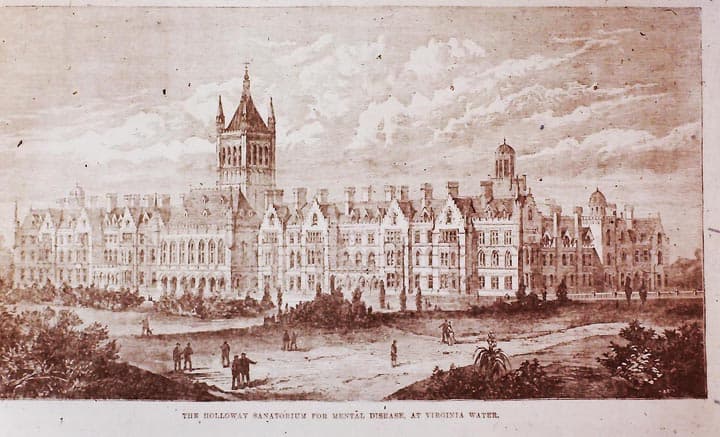

Holloway is best remembered for the two large institutions which he built in England: Holloway Sanatorium in Virginia Water, Surrey, and Royal Holloway College, a college of the University of London in Englefield Green, Surrey. Both were designed by the architect William Henry Crossland, and were inspired by the Cloth Hall in Ypres, Belgium, and the Château de Chambord in the Loire Valley, France. They were founded by Holloway as “Gifts to the nation”.

Holloway claimed that it was his wife, Jane, who inspired him to found the college, which was a women-only college until 1945. Holloway also paid over £80,000 to acquire 77 Victorian era paintings which he donated to the college at the time of its founding. Most of these pieces of art still belong to the college, and remain on display today in the college’s Picture Gallery. Three of the paintings, by Turner, Constable and Gainsborough were sold in the 1990s.

Holloway had become extremely wealthy by the late 1860s and bought a Georgian House at Sunninghill, near Ascot, Berkshire called Tittenhurst Park. Holloway lived there with his wife. Her sister, Sarah Anne Driver, also lived there with her husband George Martin, as did Holloway’s sister Matilda, an invalid who died soon after. Jane died in 1875, aged 61; Holloway died there on 26 December 1883, aged 83.

The grave of English philanthropist Thomas and Jane Holloway at St. Michael and All Angels Church, Sunninghill, Berkshire, England.

A philanthropic and somewhat eccentric donor (he had an unconcealed prejudice against doctors, lawyers and parsons), Holloway died of congestion of the lungs at Sunninghill in 1883, eighteen months before the opening of the Holloway Sanatorium. He is buried with his wife Jane in a family grave at Sunninghill churchyard. [wikipedia and other online sources]

Holloway Collateral Pieces

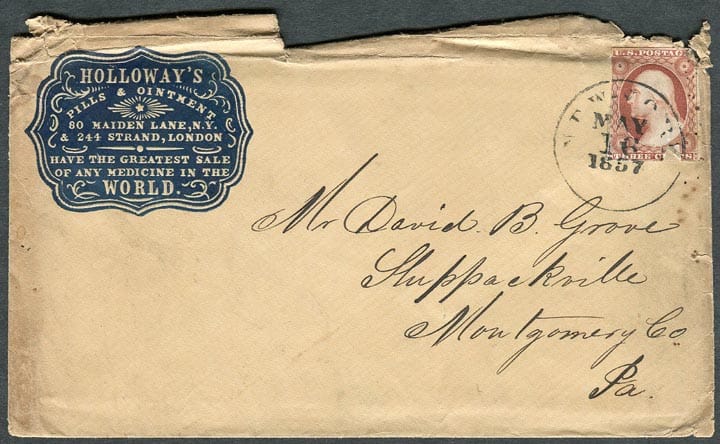

Advertising cover from Holloway’s Pills & Ointments in New York (and London) mailed May 16, 1857 to Montgomery County, PA. – ebay

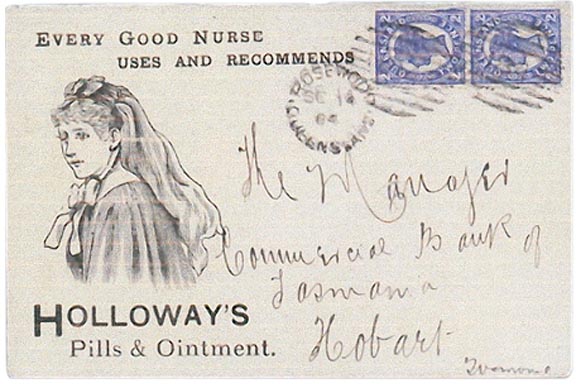

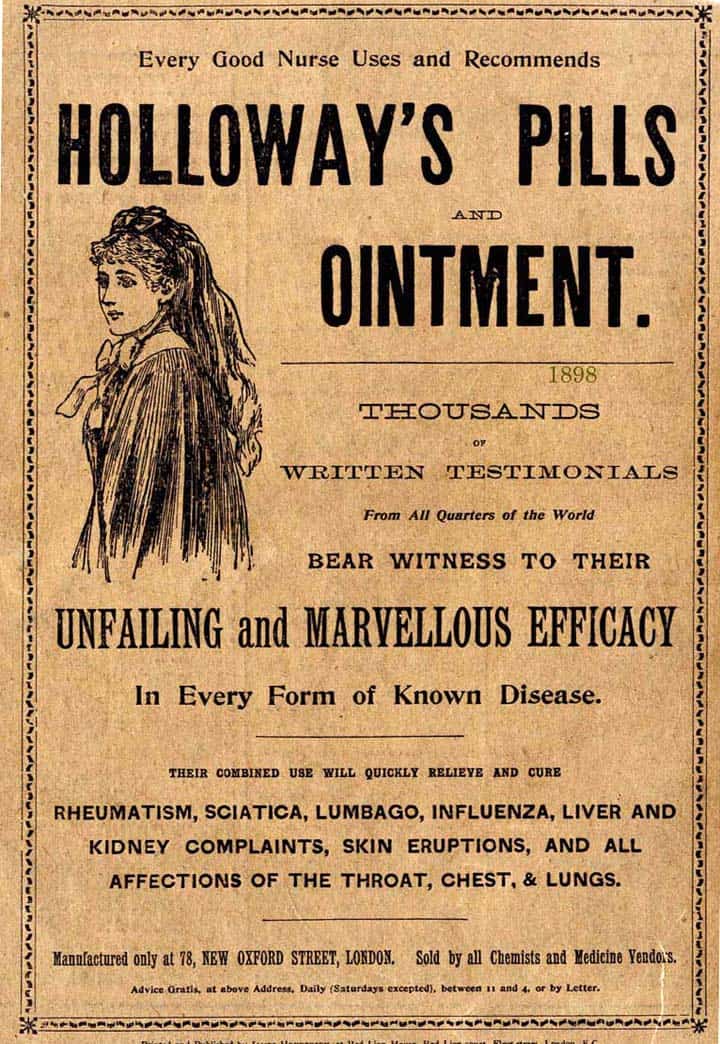

A similar, but different, “Every Good Nurse” advert praising the Holloway Pills and Ointments cover sent from Rosewood, Queensland to Hobart with two blue 1d ‘figures in four corners’ stamps in 1904 – Australian Postal History

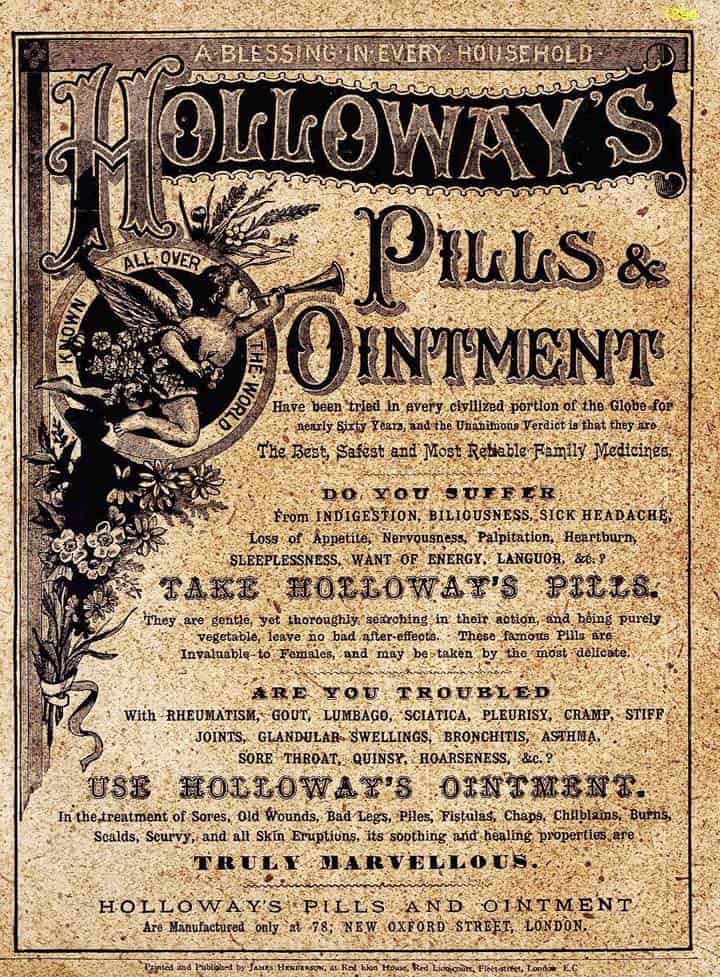

Holloway’s Pills & Ointment Advertisement – London – fulltable.com

Holloway’s Pills & Ointment Advertisement – London – fulltable.com

Holloway’s Pills & Ointment Advertisement – London – fulltable.com