T. Bewick. “Gin and Bitters”. The Sportsman’s Cabinet, 1803. – A History of the Cries of London Ancient and Modern

Tracking Hodges’ Bitters back to London?

09 June 2014

![]() Some of the earliest American bitters brands and formulas obviously came from Germany, England and other parts of Europe. We saw this the other day with the Hungarian Bitters which led me to Hodge’s Bitters from New York. I suspect this brand is English and was curious if I could find some roots in London.

Some of the earliest American bitters brands and formulas obviously came from Germany, England and other parts of Europe. We saw this the other day with the Hungarian Bitters which led me to Hodge’s Bitters from New York. I suspect this brand is English and was curious if I could find some roots in London.

“as useless as a Stoughton’s bottle”

Many bitters collectors have heard of the early and famous Stoughton’s Bitters as it appears on many old shipping and inventory lists on both sides of the Atlantic for over 100 years. This is the bitters that started it all. The brand is known to have many manufacturers and the label has been found on a number of bottles. You won’t find an embossed bottle in collections though, at least as far as I am aware.

1762: Stoughton’s Bitters by the gallon or smaller quantity. Made from tansy, orange and sukeron water. – Pennsylvania Gazette, March 29, 1762

Stoughton’s was first patented in England and was produced and sold around 1712. It was a mainstay of the medical community and over time, Stoughton’s gained popularity in the American colonies. Once the recipe was published, fakes flooded the market and eventually doomed the brand. Eventually there were so many poorly made Stoughton’s bitters knockoffs that the term “as useless as a Stoughton’s bottle” entered the lexicon in the mid 1800s. Thinking of Hostetter’s here now.

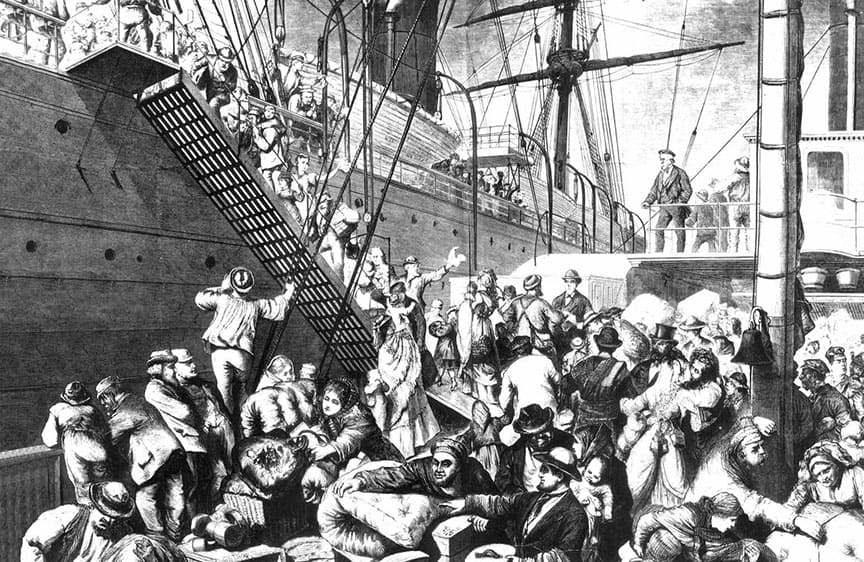

“From the Old to the New World” shows German emigrants boarding a steamer in Hamburg, to New York – Harper’s Weekly, (New York) November 7, 1874

Many great men, with bitters formulas, came with the The Forty-Eighters who were Europeans who participated in or supported the revolutions of 1848 that swept Europe. In Germany, the Forty-Eighters favored unification of the German people, a more democratic government, and guarantees of human rights. Disappointed at the failure of the revolution to bring about the reform of the system of government in Germany or the Austrian Empire and sometimes on the government’s ‘wanted list’ because of their involvement in the revolution, they gave up their old lives to try again abroad. Many emigrated to the United States, after the revolutions failed. They included Germans, Czechs, Hungarians, and others. Many were respected, wealthy, and well-educated; as such, they were not typical migrants. A large number went on to be very successful as we know. This is when the first Ferdinand Meyer came to America as I have traced him to a ship arriving from Bremen to New York and then to Baltimore. No there wasn’t a Meyer’s Bitters but old Ferdinand was working within a block or two of some Baltimore bitters manufacturers in the mid 1800s. I’m sure he bent the elbow with a few. Read: Gouley’s Vegetable Bitters – Baltimore

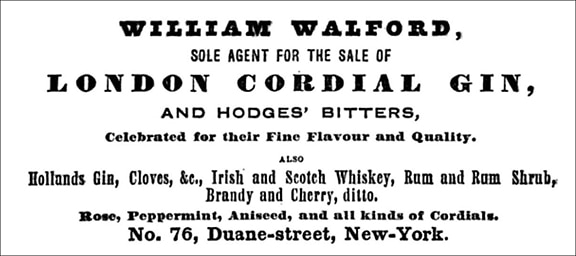

Well, back to Hodges Bitters. I found a listing in an 1845 New York City Directory for a William Walford who was the sole agent for the sale of London Cordial Gin and Hodges’ Bitters. Thinking all-the-way English here. A quick look at Bitters Bottles by Carlyn Ring and W.C. Ham reveal two listings with English inference:

H 129 Hodge’s Gin Bitters, Brooklyn Directory (N.Y.) 1836-37

H 130 Hodge’s London Bitters, New York Directory 1844-45

Here are a few other pieces of information from various newspapers in New york.

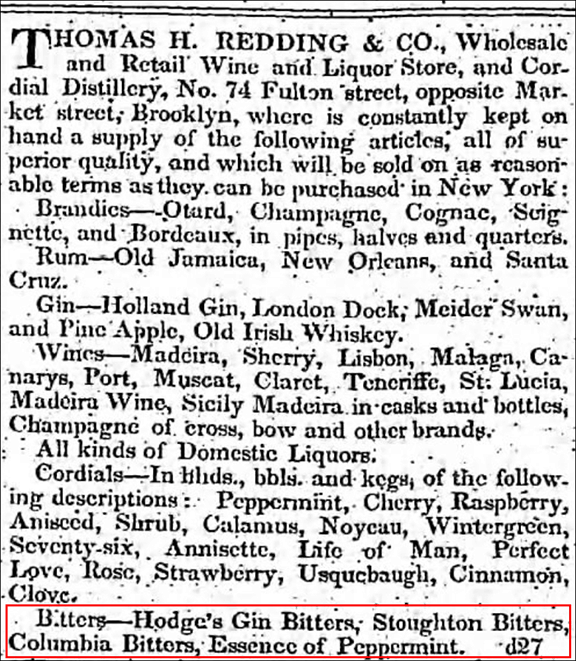

Thomas H. Redding & Co. advertisement in Brooklyn, New York selling Hodge’s Gin Bitters, Stoughton Bitters, Columbia Bitters and Essence of Peppermint. – Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 29, 1841

1841: Thomas H. Redding & Co. in Brooklyn, New York (see ad above) selling Hodge’s Gin Bitters, Stoughton Bitters, Columbia Bitters and Essence of Peppermint. – Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 29, 1841

William Walford, Sole Agent for the Sale of London Cordial Gin and Hodges’ Bitters – 1845 New York City Directory

1845: Advertisement for William Walford, Sole Agent for the Sale of London Cordial Gin and Hodges’ Bitters – 1845 New York City Directory

1850: S. Barnett, Hodge’s Bitters, Patent Medicines, 79 W. Broadway – New York County – The New York Mercantile Union Business Directory

1857: William Walford, late liquors, h 127 W. Broadway – New York City Directory

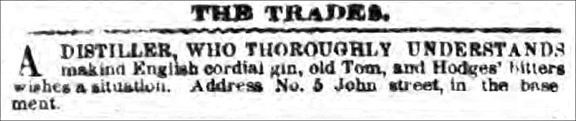

1859: A Distiller Wanted for Hodges Bitters advertisement (see above) – New York Herald

So with all of these different people selling versions of Hodge’s bitters, it is not difficult to imagine a fellow named Hodge who was probably from London. Could it be:

Nathaniel Hodges (1629–1688): The Plague doctor

Nathaniel Hodges was the son of Thomas Hodges (1605–1672), an influential Anglican preacher and reformer with strong connections in the political life of Carolingian London. Educated at Westminster School, Trinity College Cambridge and Christ Church College, Oxford, Nathaniel established himself as a physician in Walbrook Ward in the City of London.

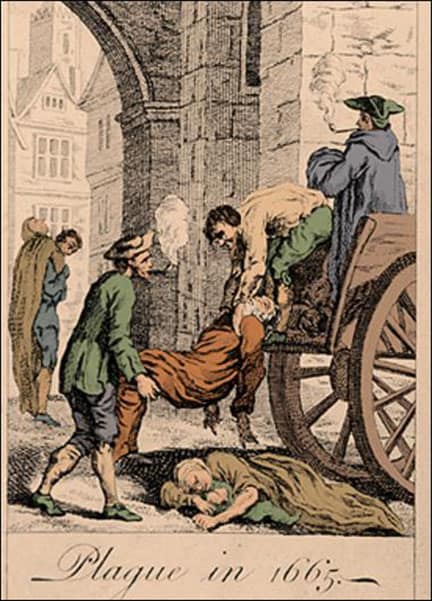

Collecting the dead for burial during the Great Plague. The Great Plague (1665–66) was the last major epidemic of the bubonic plague to occur in the Kingdom of England. Source: The Great Plague of London

Prominent as one of a handful of medical men who remained in London during the time of the Great Plague of 1665, he wrote the definitive work on the outbreak. His daily precautions against contracting the disease included fortifying himself with Théodore de Mayerne’s anti-pestilential electuary and the liberal consumption of sack, dining soon after, usually off roast meat with pickles or other relish. He drank more wine at dinner. Afterwards he saw patients at his own house, and paid more visits, returning home between eight and nine o’clock. He spent the evening at home, never smoking, but drinking old sack till he felt thoroughly cheerful. After this he generally slept well. He rose early, and took a dose of anti-pestilential electuary as large as a nutmeg. After transacting his household affairs he entered his consulting room. Crowds of patients were always waiting, and for three hours he examined them and prescribed, finding some who were already ill, and others only affected by fear. When he had seen all, he breakfasted, and visited patients at their houses. On entering a house he had a disinfectant burnt on hot coals, and if hot or out of breath rested till at his ease, then put a lozenge in his mouth and proceeded to examine the patient.

Twice during the epidemic he felt as if the plague had infected him, but after increased draughts of sack he felt well in a few hours, and he escaped without serious illness. In recognition of his services to the citizens during the plague, the authorities of the city granted him a stipend as their authorised physician.

Hodges’ approach to the treatment of plague victims was empathetic and based on the traditional Galenic method rather than Paracelsianism although he was pragmatic in the rejection of formulae and simples which he judged from experience to be ineffective. Besieged by financial problems in later life, his practice began to fail and Hodge was imprisoned in Ludgate Prison (debtors prison) for debt, and there died on 10 June 1688. He was buried in St. Stephen’s, Walbrook, and a bust and inscription were to be seen there. [passages from Christopher J. Duffin, Earth Science Department, The Natural History Museum, London, UK and Wikipedia]