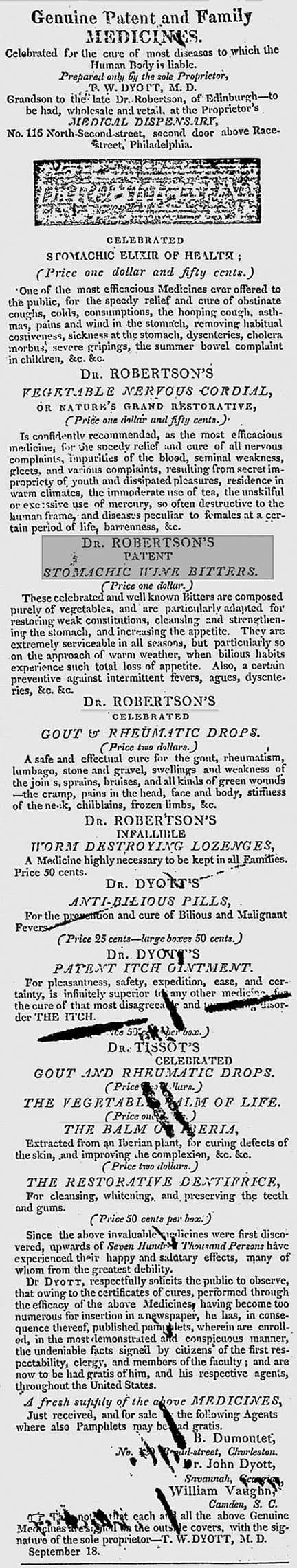

Advertisement: Dr. Robertson’s Medicines preparedly T.W., Dyott – Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, Friday, February 16, 1810

Was there really a Dr. Robertson?

30 August 2014 (R•100318)

Dr Robertson’s Family Medicine / Prepared only by T.W. Dyott 1809-1815, a T.W. Dyott small vial, 1810 to 1825, Daffys True Elixir, Lee’s Prepared by Noah Ridgley Baltimore, Liquid Opadeldoc, Robert Turlington Balsam Of Life 1754 to 1780, Robert Turlington Balsam Of Life 1790 to 1810, True Cephalick Snuff 1810 to 1830, Dalbys Carminative 1820 to 1830 and Macassar Oil London 1815 to 1830. – Stephen Atkinson Collection

Read: Check these T. W. Dyott bottles out!

Read: Dyottville Glass

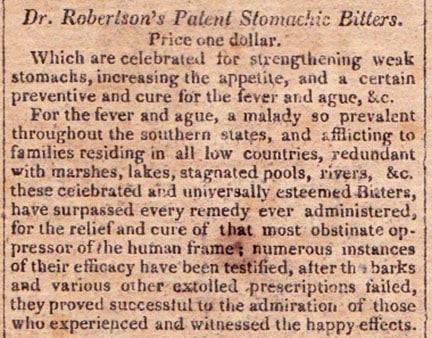

![]() I received an original newsprint copy from Carl T. Hotkowski of the Connecticut Mirror (Hartford) from Monday, June 26, 1820. Within that newspaper were a few advertisements for bitters including the Cooley’s Anti Dispeptic Bitters and the Dr. Robertson’s Patent Stomachic Bitters. Carl certainly knows how to get my attention.

I received an original newsprint copy from Carl T. Hotkowski of the Connecticut Mirror (Hartford) from Monday, June 26, 1820. Within that newspaper were a few advertisements for bitters including the Cooley’s Anti Dispeptic Bitters and the Dr. Robertson’s Patent Stomachic Bitters. Carl certainly knows how to get my attention.

Dr. Robertson’s Patent Stomachic Bitters advertisement – Connecticut Mirror (Hartford), Monday, June 26, 1820

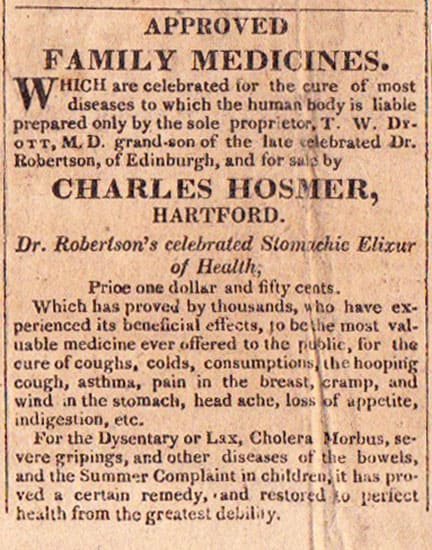

T. W. Dyott, M.D. grand-son of the late celebrated Dr. Robertson, of Edinburgh – Connecticut Mirror (Hartford), Monday, June 26, 1820

The Carlyn Ring and W.C. Ham listing in Bitters Bottles is as follows:

R 78 ROBERTSON’S STOMACHIC BITTERS Prepared and sold by T.W. Dyott, M.D., Philadelphia Dr. T.W. Dyott Drug Catalog 1820 Newspaper Advertisement 1824, also mentions Robertson’s Nervous Cordial, Robertson’s Stomachic Elixir of Health. Western Courier (Elliotsville, New York) November 29, 1826 New York Statesman October 9, 1829

R 79 DR ROBERTSON’S STOMACH WINE BITTERS Advertised from 1809-1820. Possibly predecessor to the preceding.

T. W. Dyott, M.D. grand-son of the late celebrated Dr. Robertson, of Edinburgh – The Times (Charleston), Tuesday Evening, October 30, 1810

What is interesting is that T.W. Dyott used to proclaim that he was the grandson of the late and celebrated Dr. Robertson, of Edinburgh, Scotland. This could be a reference to William Robertson as he was certainly well known and celebrated. Did he make medicines though? Dyott also said he was a doctor. I have had trouble making these connections in the past but not today as I visit a reference from The Toadstool Millionaires: A Social History of Patent Medicines in America before Federal Regulation, Chapter 3: Vials and Vermifuges, James Harvey Young, PhD. Specifically the passage, “Most of these creations bore the name of a Dr. Robertson. This worthy, Dyott asserted in his advertising, was his own grandfather, a distinguished physician in Edinburgh. The enterprising editor of a Philadelphia medical journal, looking into the matter, discovered that there had been no noted Dr. Robertson in Edinburgh for nearly two centuries. This intelligence did not disturb Dyott in the least.” This same information is echoed in “The first century of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy, 1821-1921”. Maybe Dyott was related, or maybe he just used the name and embellished his relationship. It wouldn’t be the first time and certainly not the last time that we will see this type of marketing.

Two and a half very rare medicine bottles. Two bottles embossed Dr Robertsons Family Medicine Prepared Only By T W Dyott and a Lee’s Valuable Family Medicine Prepared by Noah Ridgley – Stephen Atkinson Collection

Chapter 3: Vials and Vermifuges

Dr. Thomas Dyott

[a selection from The Toadstool Millionaires] A man named Dyott surpassed all his rivals during the first generation and became the king of nostrum makers in the American republic.

At the start Dyott relied heavily on a compound for the cure of “a certain disease,” but soon he was producing a long line of remedies similar to those of Richard and Michael Lee. Most of these creations bore the name of a Dr. Robertson. This worthy, Dyott asserted in his advertising, was his own grandfather, a distinguished physician in Edinburgh. The enterprising editor of a Philadelphia medical journal, looking into the matter, discovered that there had been no noted Dr. Robertson in Edinburgh for nearly two centuries. This intelligence did not disturb Dyott in the least. He went on vending Robertson’s Infallible Worm Destroying Lozenges and the other priceless preparations devised by his honored progenitor, and he made bold to claim a more lofty dignity himself, assuming the title of Doctor of Medicine and fabricating a tale of long experience as a physician in London, the West Indies, and Philadelphia.

Business boomed. Dr. Dyott’s advertisements were displayed prominently in daily papers, of the Eastern cities and occupied columns of space in the rural weeklies of the hinterland. Better to service his far-flung market, Dyott established agencies in New York, Cincinnati, New Orleans, and other cities. His advertisements featured drawings of large Conestoga wagons being loaded from his capacious warehouses with nostrums for the South and West. Besides his own brands, Dyott distributed the old English patent medicines, and the pills and potions of his rivals, among them the bilious pills of Samuel H. P. Lee.

As Thomas Dyott, early in his career, had expanded from blacking to nostrums, so later he enlarged his enterprises again and again. Living in the day of a barter economy, the shrewd merchandiser accepted produce for patent medicines. Soon he was dealing in such things as tobacco and turpentine, peach brandy and rum, candles and castor oil. The scope of his nostrum sales required thousands of bottles, an article he had first required while vending blacking, so Dyott acquired, first, an interest in a glass works, and then full ownership of a large factory on the Delaware River near Philadelphia. Dyott not only undercut the prices of imported British glassware, but soon was turning out the best grade of bottle glass in America. One product of his factory, preserved in the Smithsonian Institution, was a double portrait flask, honoring those two distinguished adopted sons of Philadelphia, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Dyott [10]. By the 1830’s Dyott was living extravagantly on a princely income of $25,000 a year. His personal estate was said to be worth $250,000. He dressed oddly and drove about in style, with four horses attached to his elegant English coach and several outriders in attendance. A man with such expansive vision who had achieved so much was perhaps bound to fancy himself a humanitarian. A pioneer at price-cutting, Dyott had offered to sell his remedies to the “laboring poor at one-half the usual price.” For his own laborers he sought to turn his factory into a sort of model community. Whatever the proportion of alcohol in his remedies, the nostrum king permitted no spirituous liquors in Dyottsville. He made this clear in a high-toned pamphlet composed by his own hand and garnished with classical quotations. Nor was his establishment to be disgraced by swearing, fighting, or gambling. Infractions brought deductions from pay. The former druggist’s apprentice decreed that his own hundred apprentices, who lived on the grounds, be taught reading, writing, arithmetic, and singing. They must also bathe and go to Sunday School. They worked a ten-hour day.