Not much known about the Acorn Bitters

… or How to Make Acorn Gruel

22 December 2014

![]() I don’t know about you but whenever I think about an acorn, I think about ole Henny Penny. I read and re-read this story to my grand-kids with delight because it is so darn funny and it applies to some people and situations that are all to real to me. Life is full of irony.

I don’t know about you but whenever I think about an acorn, I think about ole Henny Penny. I read and re-read this story to my grand-kids with delight because it is so darn funny and it applies to some people and situations that are all to real to me. Life is full of irony.

Henny Penny, more commonly known as Chicken Little and sometimes as Chicken Licken, is a folk tale with a moral in the form of accumulative tale about a chicken who believes the world is coming to an end when an acorn falls on her head. The phrase “The sky is falling!” features prominently in the story, and has passed into the English language as a common idiom indicating a hysterical or mistaken belief that disaster is imminent. Versions of the story go back more than 25 centuries; it continues to be referenced in a variety of media.

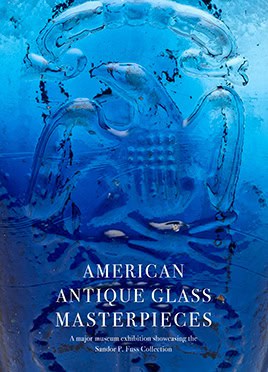

The bottle picture at the top post position above is from Jeff Wichmann and represents one of his many outstanding bottles on his new American Bottle Auctions | Bottle Store page. His description for the Acorn Bitters:

Acorn Bitters: Almost 9” with tooled top. (A 9) Here’s a western bitters we don’t see a lot. We have sold one with an applied top but most are tooled. Not a lot is known about them aside from the fact they are found in the west and probably made in the 1890’s. Good strike, some light and fairly minor scratches here and there, this is an uncleaned and very presentable example. Considered rare. Grades a 9.2.

Jeff is right. There is virtually no information on this bottle. I did find this interesting article on how the Yosemite indians in California took the bitter acorns to make gruel. Kind of interesting. Maybe the foundation for this bitters. Always wondered why white men don’t eat acorns.

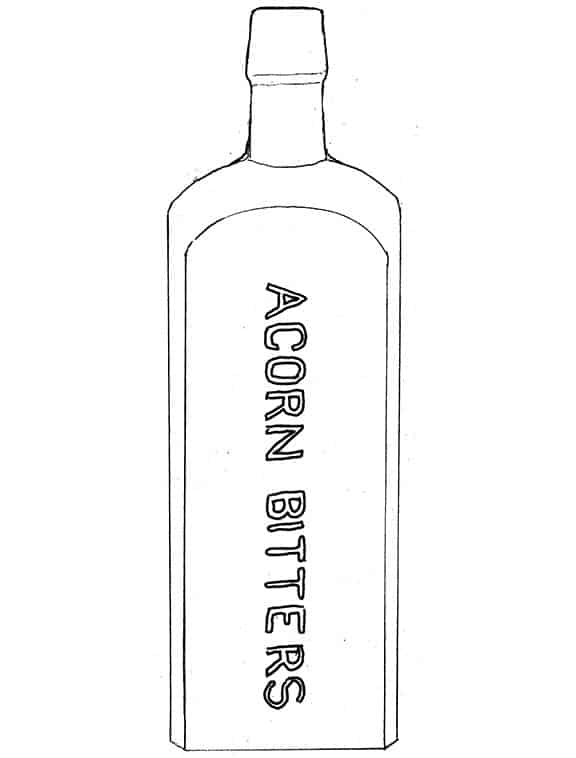

The Carlyn Ring and W.C. Ham listing in Bitters Bottles is as follows:

A 9 ACORN BITTERS

ACORN BITTERS // f // f // f //

Square, Amber LTC, Tooled lip, Very Rare

Believed to be of Western manufacture

the Yosemites, who were the most warlike of the Indian mountain tribes in California.

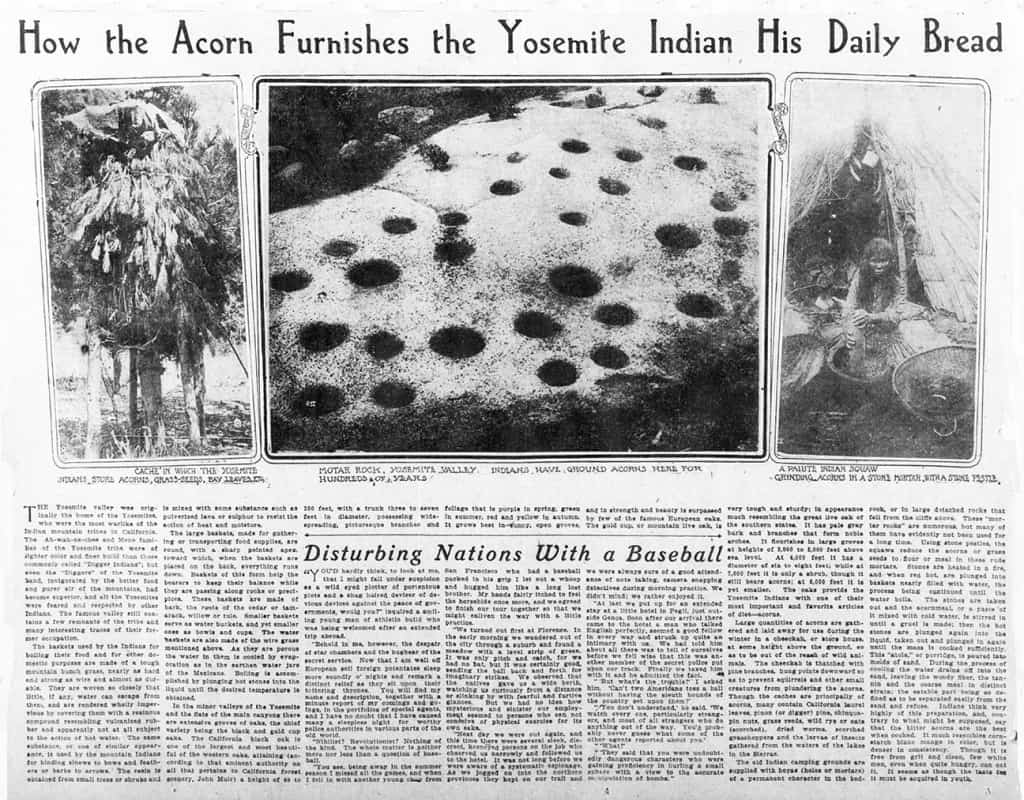

How the Acorn Furnishes the Yosemite Indian His Daily Bread

THE Yosemite valley was originally the home of the Yosemites, who were the most warlike of the Indian mountain tribes in California. The Ah-wah-ne-chee and Mono families of the Yosemite tribe were of lighter color and finer build than those commonly called “Digger Indians”; but even the “Diggers” of the Yosemite land, invigorated by the better food and purer air of the mountains, had become superior, and all the Yosemite’s were feared and respected by other Indians. The famous valley still contains a few remnants of the tribe and many interesting traces of their former occupation.

The oaks provide the Yosemite Indians with one of their most important and favorite articles of diet – acorns.

The baskets used by the Indians for boiling their food and for other domestic purposes are made of a tough mountain bunch grass, nearly as hard and strong as wire and almost as durable. They are woven so closely that little, if any, water can escape from them, and are rendered wholly impervious by covering them with a resinous compound resembling vulcanized rubber and apparently not at all subject to the action of hot water. The same substance, or one of similar appearance, is used by the mountain Indians for binding sinews to bows and feathers or barbs to arrows. The resin is obtained from small trees or shrubs and is mixed with some substance such as pulverized lava or sulphur to resist the action of heat and moisture.

Though the caches are principally of acorns, many contain California laurel leaves, pinon (or digger) pine, chinquapin nuts, grass reeds, wild rye or oats (scorched), dried worms, scorched grasshoppers and the larvae of insects gathered from the waters of the lakes in the Sierras.

The large baskets, made for gathering or transporting food supplies, are round, with a sharp pointed apex, toward which, when the baskets are placed on the back, everything runs down. Baskets of this form help the bearers to keep their balance while they are passing along rocks or precipices. These baskets are made of bark, the roots of the cedar or tamarack, willow or tule. Smaller baskets serve as water buckets, and yet smaller ones as bowls and cups. The water baskets are also made of the wire grass mentioned above. As they are porous, the water in them is cooled by evaporation as in the earthen water jars of the Mexicans. Boiling is accomplished by plunging hot stones into the liquid until the desired temperature is obtained.

In the minor valleys of the Yosemite and the flats of the main canyons there are extensive groves of oaks, the chief variety being the black and gold cup oaks. The California black oak is one of the largest and most beautiful of the western oaks, attaining (according to that eminent authority on all that pertains to California forest scenery, John Muir) a height of 60 to 100 feet with a trunk three to seven feet in diameter possessing wide-spreading, picturesque branches and foliage that is purple in spring, green in summer, red and yellow in autumn. It grows best in sunny, open groves, and in strength and beauty is surpassed by few of the famous European Oaks. The gold cup, or mountain live oak, is very tough and sturdy; in appearance much resembling the great live oak of the southern states. It has pale gray bark and branches that form noble arches. It flourishes in large groves at heights of 3,000 to 6,000 feet above sea level. At 4,000 feet it has a diameter of six to eight feet; while at 7,000 feet it is only a shrub though it still bears acorns; at 8,000 feet it is yet smaller. The oaks provide the Yosemite Indians with one of their most important and favorite articles of diet – acorns.

Though it is free from grit and clean, few white men, even when quite hungry, can eat it. It seems as though the taste for it must be acquired in youth.

Large quantities of acorns are gathered and laid away for rise during the winter in a cheeckah, or store house, at some height above the ground, so as to be out of the reach of wild animals. The cheeckah is thatched with pine branches, hung points downward so as to prevent squirrels and other small creatures from plundering the acorns. Though the caches are principally of acorns, many contain California laurel leaves, pinon (or digger) pine, chinquapin nuts, grass reeds, wild rye or oats (scorched), dried worms, scorched grasshoppers and the larvae of insects gathered from the waters of the lakes in the Sierras.

The old Indian camping grounds are supplied with hoyas (holes or mortars) of a permanent character in the bed rook, or in large detached rocks that fell from the cliffs above. These mortar rocks are numerous, but many of them have evidently not been used for a long time. Using stone pestles, the squaws reduce the acorns or grass seeds to flour or meal in these rude mortars. Stones are heated in a fire and when red hot, are plunged into baskets nearly filled with water, the process being continued until the water boils. The stones are taken out and the acornmeal, or a paste of it mixed with cold water, is stirred in until a gruel is made; then the hot stones are plunged again into the liquid, taken out and plunged in again until the mass is cooked sufficiently. This “atola,” or porridge, is poured into molds of sand. During the process of cooling the water drains off into the sand, leaving the woody fiber, the tannin and the coarse meal in distinct

strata; the eatable part being so defined as to be separated easily from the sand and refuse. Indians think very highly of this preparation, and, contrary to what might be supposed, say that the bitter acorns are the best when cooked. It much resembles cornstarch blanc mange in color, but is denser in consistency. Though it is free from grit and clean, few white men, even when quite hungry, can eat it. It seems as though the taste for it must be acquired in youth.