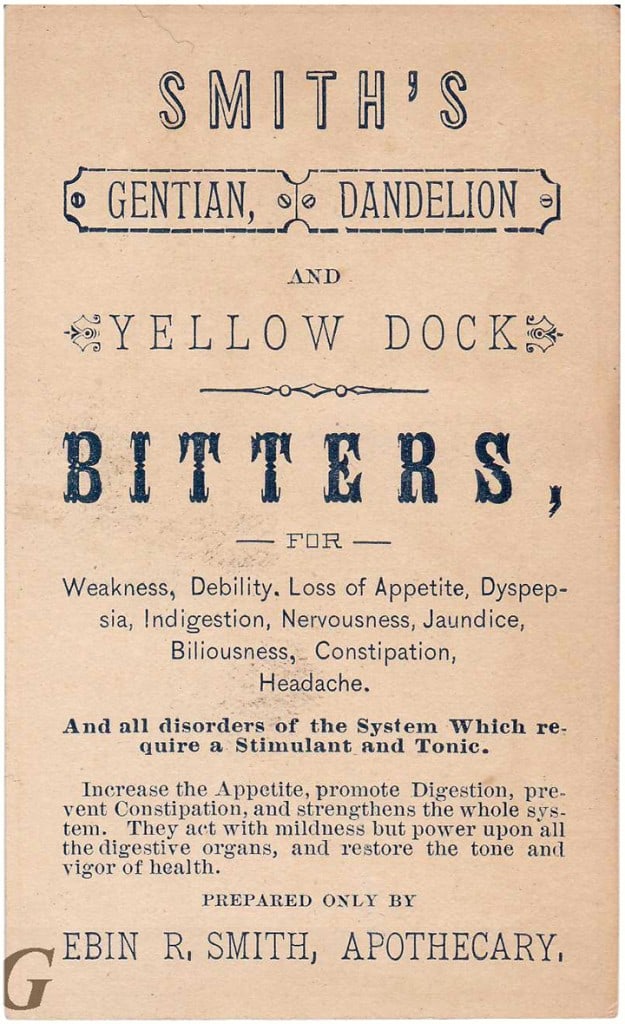

Smith’s Gentian, Dandelion and Yellow Dock Bitters

Ebin R. Smith, Apothecary

08 February 2015 (R•090119)

![]() The Smith’s Gentian, Dandelion and Yellow Dock Bitters appears to be unlisted in Bitters Bottles. You have to look carefully as there are about 15 brands of Smith’s bitters of one sort or local or another. This brand was put out by Ebin R. Smith practicing as a druggist out of Ipswich, Massachusetts. The trade card is from the Joe Gourd collection. Another in the series focusing on dandelion bitters brands.

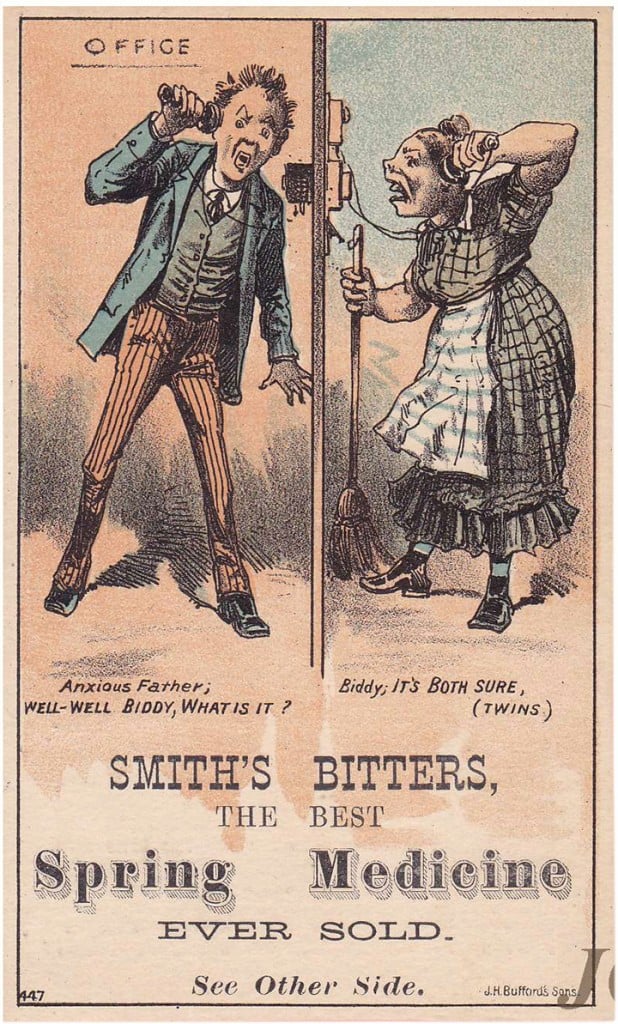

The Smith’s Gentian, Dandelion and Yellow Dock Bitters appears to be unlisted in Bitters Bottles. You have to look carefully as there are about 15 brands of Smith’s bitters of one sort or local or another. This brand was put out by Ebin R. Smith practicing as a druggist out of Ipswich, Massachusetts. The trade card is from the Joe Gourd collection. Another in the series focusing on dandelion bitters brands.

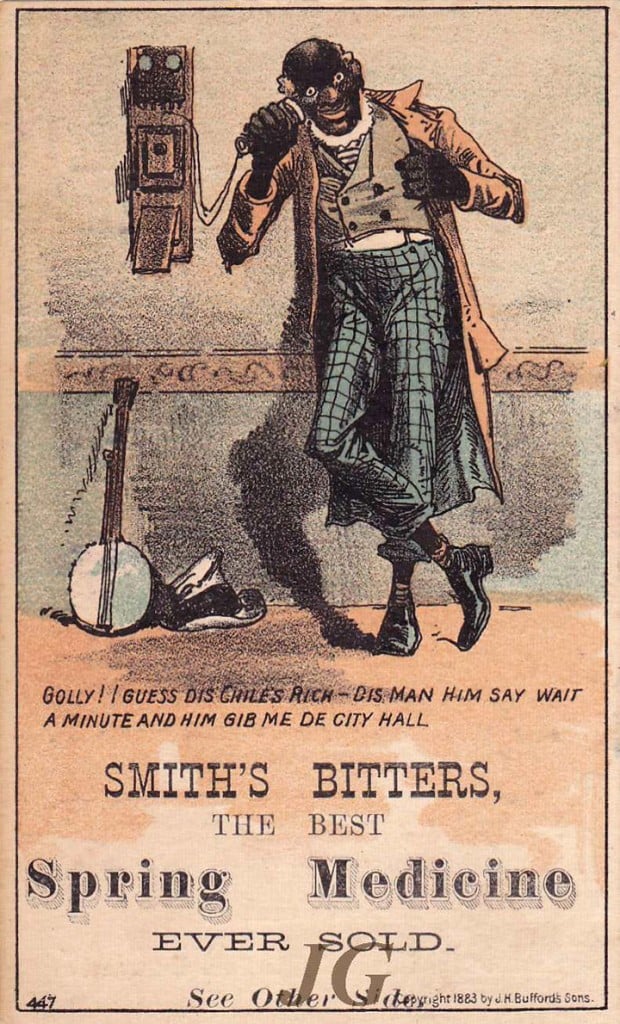

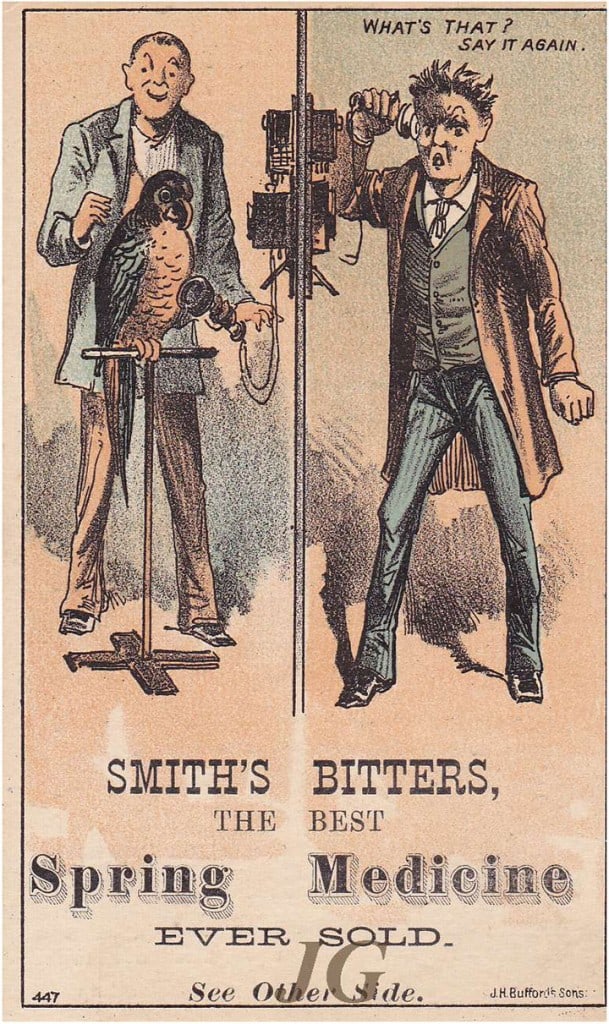

I typically barely crack a smile at some of the odd humor on these advertising trade cards. This one is no exception. With the new telephone era evident, we have an anxious ‘business type’ father being told by his ‘maid looking’ wife, her name is Bitty you see, that there are ‘two are in the oven’ so to speak. The business guys knows things are going to change. Maybe time to get some Smith’s Bitters!

The new listing in Bitters Bottles Supplement 2:

Trade cards

S 124.5 SMITH’S GENTIAN, DANDELION AND YELLOW DOCK BITTERS, Humorous illustrations of people talking on telephone. Smith’s Bitters, The Best Medicine Ever Sold. Reverse: Smith’s Gentian, Dandelion and Yellow Dock Bitters, Prepared only by Ebin R. Smith, Apothecary.

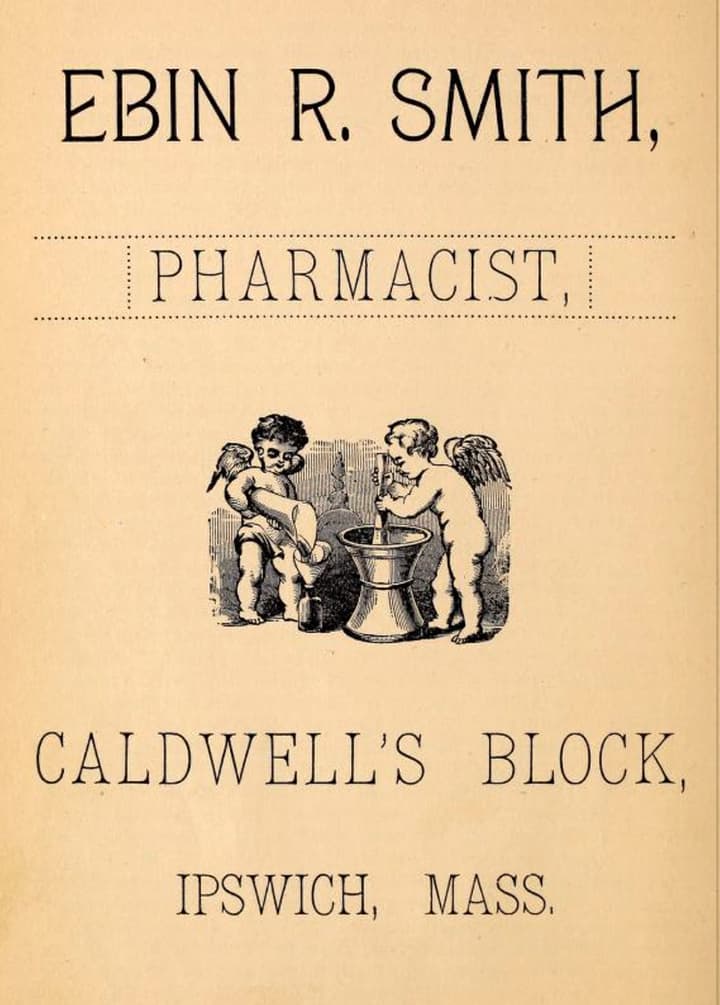

Ebin R. Smith, apothecary, druggist, Market sq, Caldwell’s blk, home 48 Central – Ipswich, Massachusetts City Directory, 1888-1891

Ebin Ryder Smith

Ebin Ryder Smith was born in Boston, Massachusetts on December 6, 1862. His father, Theophilus Smith, was a druggist so Ebin Ryder seemed destined to follow his father’s footsteps. Ebin, and you sometimes see it incorrectly spelled Eben, next appears with an Apothecary shop on South Main Street at Caldwell’s Block in Ipswich, Massachusetts in 1884. He would remain in Ipswich most of his career as a druggist. Mr. Smith would practice as a Pharmacist up until about 1908. He died at a relatively young age in 1911.

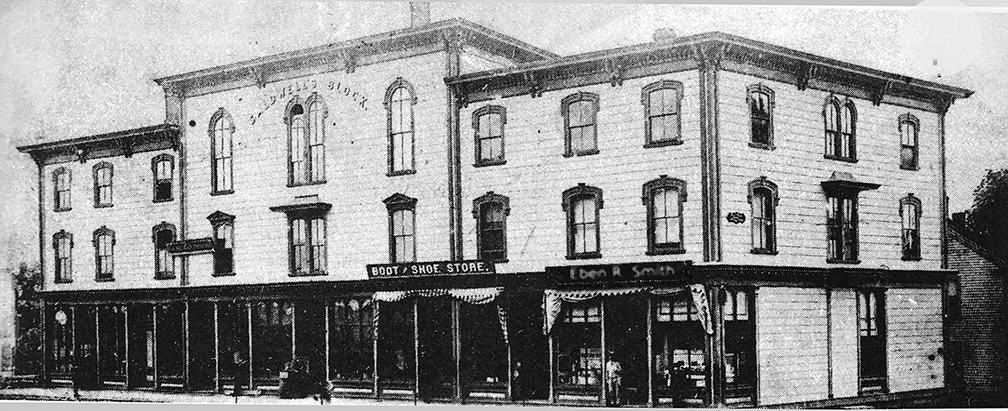

The Caldwell Block is a historic block on S. Main Street in Ipswich, Massachusetts. If you look carefully you can see the Smith drug store on the right. That probably is Ebin Ryder Smith standing out front. I do feel that this photograph was embellished or manipulated as the sign is spelled wrong on the store front.

The Caldwell Block is a historic block on S. Main Street in Ipswich, Massachusetts. It is the oldest surviving building in Ipswich that was designed as a commercial and retail space, and is still used for that purpose. It is located prominently in the center of Ipswich, at the junction of North and South Main Streets, and Central and Market Streets. It was built in 1870 by Luther Caldwell, on the site of an old woolen mill that was destroyed by fire a few years earlier, and features Italianate styling. The building has always housed retail stores on the ground floor and office space above. It is notable as the location of the offices of writer John Updike between 1961 and 1974, when he wrote many of his works there. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1983.

If you look carefully at this 1832 illustrative map of Ipswich, you can see the Smiths Buildings at the intersection of Market and South Main Street. I wonder if this was a relative of Theophilus Smith, the father. He was a druggist in Boston. This would be the location of Caldwell’s Block.

The Smith’s Gentian, Dandelion and Yellow Dock Bitters could have been his biggest seller and was probably a labeled bitters in the mid 1880s. I am aware of no examples in collections.

For you legal types in the crowd, Ebin R. Smith and Edward R. Brown had an interesting case where a ‘non-compete’ contract must have been signed between the two. Read about the case below in 1895.

EBIN R. SMITH vs. EDWARD F. BROWN.

Essex. November 6, 1895. – November 27, 1895.

Present: FIELD, C. J., HOLMES, KNOWLTON, MORTON, & LATHROP, JJ.

Restraint of Trade – Valid Contract – Injunction – Penalty – Damages.

B. signed an agreement which recited that for value received of A., and for the further consideration of A. “taking from me my lease of an apothecary shop in I my promise herein being the chief inducement leading him to take said lease, and to purchase the property therein, and in said shop and the good will of the business, – I hereby agree with said A. . . . under a penalty of one thousand dollars (to be forfeited and paid said A. or his legal representatives, in the event of my committing any breach of this agreement) not to engage directly or indirectly, or become in any manner interested, in the drug business within at least two miles of said apothecary shop, whose lease said A. takes from me, without first obtaining the written consent of said A. thereto.” Held, on a bill in equity for an injunction for a violation of the contract, and for the payment of one thousand dollars as liquidated damages, that the contract was valid; that, as there was evidence of laches on the part of A., an injunction was rightly refused; that the sum named was a penalty, and that the judge was warranted in finding substantial damages.

BILL IN EQUITY, filed February 21, 1895, to restrain the defendant from continuing in the drug business in Ipswich, in violation of his contract with the plaintiff, and for the payment of one thousand dollars as provided therein. The answer set up, among other defences, laches. In the Superior Court a decree was entered that the plaintiff recover of the defendant the sum of seven hundred and fifty dollars, with costs, without any reference to an injunction; and both parties appealed to this court. The contract and the facts of the case appear in the opinion.

E. R. Thayer, for the defendant.

E. P. Moulton, (F. V. Wright with him,) for the plaintiff.

HOLMES, J. This is a bill praying for an injunction and for damages on the following contract: “For value received of Ebin R. Smith, of East Cambridge, in the county of Middlesex, the receipt of which is hereby acknowledged, and for the further consideration of said Smith taking from me my lease of an apothecary shop in Ipswich, in the count}’ of Essex, — my promise herein being the chief inducement leading him to take said lease, and to purchase the property therein, and in said shop and the good will of the business, – I hereby agree with said Smith and his assigns and legal representatives, under a penalty of one thousand dollars (to be forfeited and paid said Smith or his legal representatives, in the event of my committing any breach of this agreement) not to engage directly or indirectly, or become in any manner interested, in the drug business within at least two miles of said apothecary shop, whose lease said Smith takes from me, without first obtaining the written consent of said Smith thereto.

“Witness my hand and seal on this fifth day of May, A. D. 1884.

“Edw. F. Brown.”

The decree assessed substantial damages, and by implication refused an injunction. Both parties appeal.

In the first place the defendant says that the contract is an unlawful restraint of trade, because it is not limited to the time of the plaintiff’s continuing in the business, or otherwise. But the covenant may be presumed to have added to the value of the good will of the plaintiffs business more than it would have done if limited. It goes no further than other contracts which have been enforced by the courts, and we shall not be ingenious in discovering new grounds for holding it void. Ropes v. Upton, 125 Mass. 258. Hitchcock v. Coker, 6 Ad. & El. 438, 454, 455.

If the contract is valid the plaintiff says that he is entitled to an injunction enforcing it, or if not, then he has a right to the whole sum mentioned in the contract, which he says is to be regarded as liquidated damages. The defendant, on the other hand, argues that in the absence of evidence directed to the point the plaintiff can recover only nominal damages. We cannot say that there was no evidence of laches sufficient to warrant the judge who saw and heard the witnesses in refusing an injunction. The plaintiff admitted that he knew that a store was being prepared which he had every reason to believe would be an apothecary’s shop, that he had been told that the defendant and one Roberts were going to start a store, and that there was a good deal of talk about it. It is plain that he understood from the talk that Brown and Roberts were going to start an apothecary’s shop at the place in question. This was some months before he took any steps. He gave no notice until the bill was filed, in the latter part of February, 1895. In the mean time the defendant and Robert’s spent a considerable sum, probably more than that mentioned in the contract, in fitting up the place. They have put between twenty-five hundred and three thousand dollars into the business. Furthermore, there was evidence that the defendant signed the contract without reading it or paying any attention to it, and that the plaintiff was aware of the fact, and therefore was aware that there were special reasons for notifying the defendant, if the latter was openly proceeding with seeming innocence to do what his agreement forbade. It is not necessary to go further on this branch of the case, or to consider whether, if this evidence were submitted to us in print without a finding, we should give the plaintiff an injunction, instead of damages. See Ropes v. Upton, 125 Mass. 258, 262.

With reference to the defendant’s contention as to damages, we have no doubt that the judge who tried the case was warranted in finding substantial damages from the defendant’s competition in a small place, without evidence specifically directed to what the damage would be, just as in the case of words affecting a trader in the way of his trade. See Tripp v. Thomas, 3 B. & C. 427; Davis v. Shepstone, 11 App. Cas. 187,191. The damages, being for breach of an entire contract, of course must be assessed once for all, and necessarily are largely a matter of estimate. See Drummond v. Crane, 159 Mass. 577, 581.

The plaintiff s position raises more difficulty. We assume in favor of the plaintiff that the words “under a penalty” are not conclusive against the sum named being regarded as liquidated damages. Lynde v. Thompson, 2 Allen, 456, 459. Ropes v. Upton, 125 Mass. 258, 262. Sainter v. Ferguson, 7 C. B. 716. Sparrow v. Paris, 7 H. & N. 594. We agree that the event to which the so-called penalty is attached is one, in a certain sense, and we do not need to controvert what sometimes has been said, that in this class of cases the courts incline to treat the sum named as liquidated damages. Mopes v. Upton, 125 Mass. 258, 260. 1 Sedgwick, Damages, (8th ed.) § 418. On the other hand, the breach might vary in gravity very much according to the degree of the defendant’s share in helping competition. The judge may have found that the words used were selected by the plaintiff’s lawyer, that the contract was signed by the defendant without reading it, and without advice from any lawyer employed by him, on the faith of assurances given in the plaintiff’s presence, and that the defendant was entitled to the most favorable construction in case of any ambiguity or doubt. We cannot say that no view of the circumstances would warrant the judge in regarding this as being a penalty, as it is called in the contract. Even if the use of that word is not conclusive, it has been declared by this court, and by others, that very strong evidence would be required to authorize them to say that the parties’ own words do not express their intention in this respect. The intention to liquidate damages may not prevail in all cases, but if the intent expressed is to impose a penalty, the court cannot give the words a larger scope. Higginson v. Weld, 14 Gray, 165, 173. Taylor v. Sandiford, 7 Wheat. 13, 17. Smith v. Wainwright, 24 Vt. 97, 102, 104. Smith v. Dickenson, 3 B. & P. 630, 632. Astley v. Weldon, 2 B. & P. 346, 350.

Decree affirmed.

All advertising trade cards from the Joe Gourd Collection

Select Dates:

1862: birth Dec 6, Ebin Ryder Smith, 113 Shawmut ave, Mothers name Mary, Fathers name Theophilus, father is a Druggist, mother and father both born in Boston.

1870: Ebin R. Smith, age 7, birth about 1863, Massachusetts, home Boston Ward 4, Suffolk, Massachusetts, father Theophilus W. Smith, sister Marietta C. Smith, 3 – United States Federal Census

1872-1873: Theophilus Smith, Druggist – The Boston Directory

1880: Ebin R. Smith, age 17, birth about 1863, Massachusetts, home Boston, Suffolk, Massachusetts, father Theophilus W. Smith – United States Federal Census

1884: Apothecaries, Ebin R. Smith, South Main st., Ipswich – The Essex County Directory

1885: Initiated into Massachusetts Mason Lodge on January 14, 1885.

1888: Advertisement (see above), Ebin R. Smith, Pharmacist, Caldwell’s Block, Ipswich, Mass. – The Agawam manual and directory

1888-1891: Ebin R. Smith, m3, apothecary, druggist, Market sq, Caldwell’s blk, home 48 Central – Ipswich, Massachusetts City Directory

1895: EBIN R. SMITH vs. EDWARD F. BROWN. (see above) – Massachusetts Supreme Court Reports

1898: Boston: B. M. Evans, a well-known Ipswich drug clerk, recently returned from a two week’s vacation. He was employed at Ebin R. Smith’s pharmacy.

1900: DESCRIPTIVE. One of my clerks reported “the other day” that he had a call for “Compound Cataract Pills!” In view of the circumstances, it was funny ; but in view of the pills, and the adjective, it was funnier.” Ebin R. Smith., Ipswich, Mass., April 2, 19oo.

1900: Ebin R. Smith, Pharmacist, age 37, birth Dec 1862, Massachusetts, home Ipswich, Essex, Massachusetts, wife Mattie E. Smith, child, Theophilus W. Smith – United States Federal Census

1908: Druggists, Ebin R. Smith – The New England Business Directory and Gazetteer

1910: Ebin R. Smith, Boarder, age 46, birth, abt 1864, Massachusetts, home Milton, Norfolk, Massachusetts, wife Mattie E. Smith, – United States Federal Census

1911: Ebin Ryder Smith died on July 5, 1911.

Read more about other Dandelion Bitters

Lyman’s Dandelion Bitters – Bangor, Maine

Dandelion & Wild Cherry Bitters – Iowa

Dandelion Bitters – The Great Herb Blood Remedy

The Beggs’ and their Dandelion Bitters

Dr. J.R.B. McClintock’s Dandelion Bitters – Philadelphia