The Bust of Columbia Liberty Cap Eagle Historical Flask

22 February 2016 (R•022416) (R•031416)

![]() Just when you wonder when the long drought and absence of killer bottles will end, up comes this off-the-chart great Bust of Columbia with Liberty Cap – American Eagle historical flask in a pint size in the Glass Works Auctions #110, aptly named “The Winter Blues” auction. The flask is pictured at the top of the post and once again within.

Just when you wonder when the long drought and absence of killer bottles will end, up comes this off-the-chart great Bust of Columbia with Liberty Cap – American Eagle historical flask in a pint size in the Glass Works Auctions #110, aptly named “The Winter Blues” auction. The flask is pictured at the top of the post and once again within.

I don’t think that I have ever seen a cobalt blue pint before. There are four or five known examples, one in the Corning Museum of Glass (pictured further below), two in private collections and now one in this auction. I have seen and handled the half pint Columbia Eagle at the FOHBC 2012 National Antique Bottle Show in Reno, Nevada. The can see another example in the left position of the picture of a color run directly above. I will never forget how beautiful that small bottle felt in my hand as I admired and was astonished with the beauty of it’s every detail.

169. BUST OF COLUMBIA WITH LIBERTY CAP – AMERICAN EAGLE, (GI-119), Kensington Glass Works, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1830 – 1840, cobalt blue pint, pontil scarred base, sheared and tooled lip. An in-making chip extending from the pontil was created when the pontil rod was removed. Perfect post production condition, very bold impression and almost no trace of wear. One of only three known examples, with the other two having minor lip damage. Considered by many to be one of the most sought after of American historical flasks! From 1829 to 1837 the Philadelphia mint produced silver coins with the likeness of the ‘Bust of Liberty’ on one side and an ‘American Eagle’ on the other. On these coins the ‘Bust of Liberty’ is almost identical to the embossing on the flask. Is it a coincidence that the coin and the flask were from the same time period, and both were produced in Philadelphia? A scarce 1837 ‘Bust of Liberty’ silver quarter in extra fine condition is included with the flask. – Glass Works Auctions

Flask with Columbia and the American Eagle, Union Glass Works, Philadelphia – Corning Museum of Glass

Here is an incredible bottom fragment that was posted on the PRG Facebook yesterday showing a variant of the flask with “KENSINGTON” embossed on the bottom banner.

Columbia Eagle historical flask bottom fragment with embossed KENSINGTON beneath the embossed Columbia side. Dug in Baltimore. – Dannyboy Morris

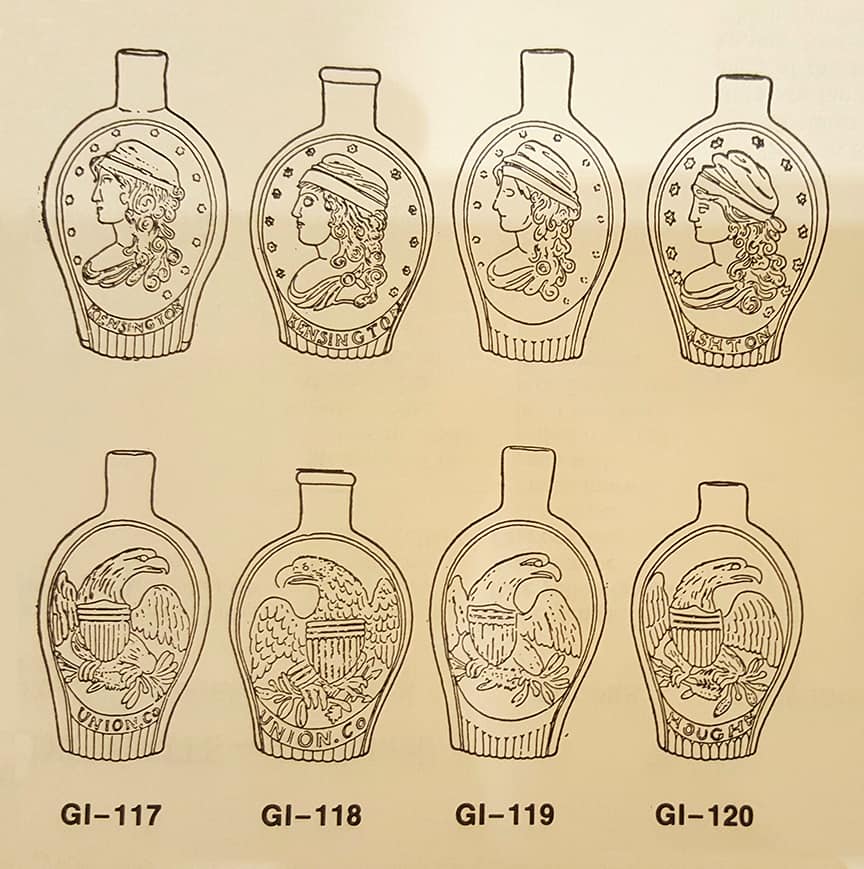

Here is a McKearin line drawing below of the various molds.

So what is this all about? What or who is Columbia, why the cap and why the eagle? There is no better place to look for the answer than reading an article that Kevin A. Sives previously wrote that he has graciously approved being reproduced here. Thank you Kevin.

Arms of the United States of America. An elaborate martial allegory of the United States. Liberty or Columbia, wearing a Phrygian cap and armed with sword, shield, and American flag, is enthroned in the clouds. The words “E Pluribus Unum” and an arc of thirteen stars appear above her. Below, an eagle perches atop a shield with the stars and strips. In his talons he holds arrows and an olive branch. At left stands an American Indian, with a bow in his hand. At right is a sailor with an anchor and four flags. Around the base of the shield are muskets, tomahawks, cannon, cannonballs, and a sword. Below, almost hidden in darkness, is a Union encampment (left) in sight of the U.S. Capitol and the Potomac River (right). 1 print on wove paper : lithograph printed in colors ; image 48 x 33.5 cm. Issued from Bufford’s Print Publishing House, 313 Washington St., Boston, c1864

Columbia the Gem of the Ocean

By Kevin A. Sives

We’ve all heard that song before. But who or what is Columbia? And what does any of this have to do with antique bottles or flasks?

Let’s start first with the song “Columbia The Gem of the Ocean” by David T. Shaw and Thomas Beckett who wrote it in 1843. It is also sometimes known as “The Red, White, and Blue”. We hear the song played at political events, high school band concerts, and even sporting events, but why are they playing some song about a country in South America?

Columbia – or Liberty

But that “Columbia” that everyone is singing about – is it a woman? A man? A country? The answer is – a little bit of everything! During America’s colonial period (prior to their forming “a more perfect Union”), our future country consisted of 13 autonomous colonies. We weren’t the United States (as a matter-of-fact, we were far from united on just about any topic you could think of). We were just “the colonies”.

By the time that the French and Indian War rolled around in the 1750s, we hadn’t given much thought to combining ourselves into a united group of colonies. But the War changed all that. Great Britain looked upon us as one country – united to fight against a common enemy – the French. By Britain forcing us to fight for them, the effect was to bring the 13 colonies together and make them think of themselves as a unified group. This unification, of course, would come back to bite the British about 20 years later.

So there we are, the 13 colonies, fighting side by side, united against the French. But we needed a name, besides just referring to us as the 13 colonies. Poets and headline writes of the time came to the rescue, and began calling this loose affiliation “Columba” (the feminine form of Columbus). It wasn’t until about the time of the Revolutionary War, however, that the name became more widely used (and lengthened to it’s current spelling, Columbia). In 1777, Timothy Dwight from New Haven, circulated a poem he wrote, called “Columbia a Patriotic Song: Written and Set to Music By Timothy Dwight”.

By the time of the death of George Washington, Columbia was well-known across the growing country as another name for the new United States. It’s difficult to have a name, without a symbol, and soon the picture of Lady Liberty came to represent Columbia. The picture of Liberty herself emerged from various renderings, the most famous being an engraving from the painting by Edward Savage, entitled “Liberty in the form of the Goddess of Youth; giving support to the Bald Eagle”, which represented her in a long flowing robe, with an American flag, an eagle, and the Liberty Cap.

The Liberty Cap? What in the world is that?

The Liberty Cap evolved from a snug fitting cap, which ended in a conical tail that was given to a slave when by the Romans when he was freed. In Rome, only free men were allowed to wear this cap. Thus, the French thought this was a fitting symbol, which they adopted during their Revolution, to represent freedom or Liberty.

On this side of the Atlantic, the Liberty Cap, or what we called the French Liberty Cap, became a well-known symbol. During and after the French Revolution, the Liberty Cap, represented as being held aloft on the end of a pole, symbolized not only freedom, but also the fight for that freedom. In the flask arena, GI-85, GI-86, and GI-87 have the Liberty Cap, on the end of a pole, on one side. The other side (and it should come as no surprise to anyone) contains a bust of a man, surmounted by the word “Lafayette”.

But to the common man, probably the representation of Columbia (or Liberty) that was encountered most often was that which appeared on our currency from 1793 until the 1830s.

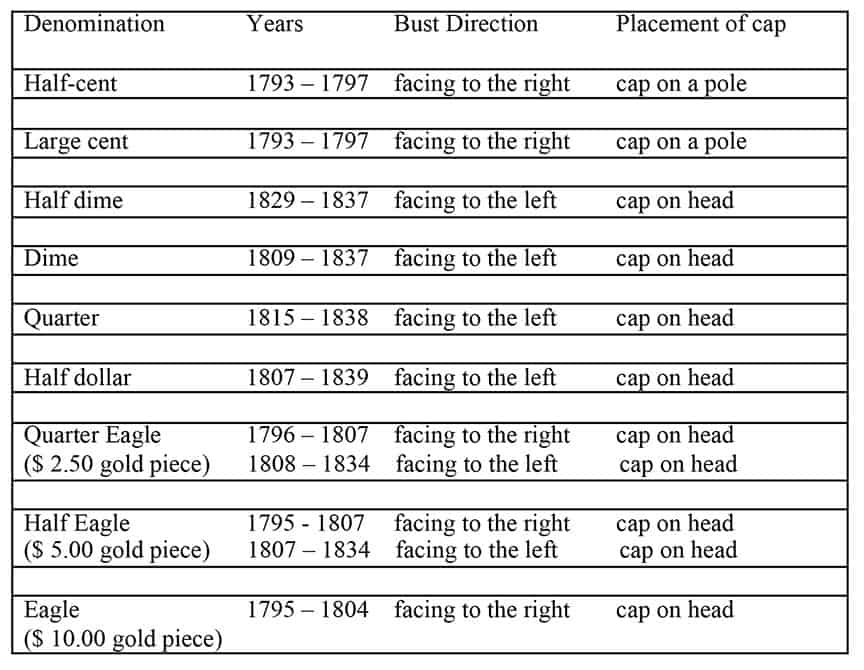

A bust view of Columbia (Liberty) can be seen on the following coin denominations:

In many instances, the cap had a band across the front with the word “LIBERTY” inscribed in it.

The version of Liberty used on the half-dime (1829 – 1837), dime (1809 – 1837), quarter (1815 – 1838), half dollar (1807 – 1839), quarter eagle (1808 – 1834), and half eagle (1807 – 1834), is very similar to the representation of Liberty that is on a majority of the historical flasks. It’s certainly quite likely that the images from the coins served as a model for the mold makers. The mold makers, realizing the popularity of the Liberty image, capitalized on this by making flasks that copied this idea. It follows then, that these flasks were made after 1807, and probably before 1840, when Liberty was highly modified on the United States coinage.

The Flasks

The GI-117 Columbia Eagle flask,another GI-117 Columbia Eagle flask and the GI-121 Flask – Historical American Glass

There are eight different flasks that represent Columbia. Seven of them, numbered GI-117 through GI-122, features a profile bust of Columbia on one side, and an eagle on the other. The eighth flask is the exception to the above, and is numbered GX-23. This flask features a seated Columbia, below the word “Liberty” in a semicircular ribbon, flanked by the initials “U S” on the front. The back contains a log cabin, tree, and water pump, above “LIBERTY!” This flask is extremely rare, and when catalogued in “American Bottles, Flasks, and Their Ancestry”, it was noted that there was only one known example, a pint, in pale bluish green. Which glasshouse made it, and when, is open to speculation. The example documented by McKearin and Wilson at one time belonged to Edwin Atlee Barber, and is now in the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio.

The remaining seven flasks, GI-117 through GI-122, plus GI-117a, are broken down as follows: one half-pint (GI-118), one slightly smaller than a half-pint at approximately 12 ounces (GI-117a), and five pints (GI-117, 119, 120, 121, and 122). On one side of each of these flasks is a profile bust view of Columbia, facing to the left, wearing a Liberty Cap on her head. Each of the renderings of Columbia is beautifully executed, with a lot of detail, and nearly identical to the busts represented on the coins described above.

On the opposite of each of these flasks is a wonderful depiction of the American eagle, and each one is slightly different from the others. All of the flasks depict an eagle with a shield, holding arrows and an olive branch. The eagle’s head faces to the right in all of the flasks, with the exception of GI-118, where the head faces left.

The first five flasks, GI-117 through GI-120, all have an oval shape, with an outward flare toward the bottom. This results in an oval flask that looks like its resting on a expanded foot. GI-121 and GI-122, on the other hand, have the more traditional oval shape associated with flasks.

GI-117, GI-117a, and GI-118 each are marked “KENSINGTON” (on the Liberty side) and “UNION Co” (on the eagle side). This quite likely refers to the Union Glass Company, which operated in the Kensington section of Philadelphia. This company was started in 1826 shut down in 1844, was reopened in 1847 and operated through 1880. These three flasks seem to date from prior to the glasswork’s first closing, as the Columbia motif disappeared from coinage in the late 1830s.

GI-119, which looks very similar to GI-117 and GI-117a, minus the glass house name, could have resulted from the mold for GI-117 being sold, and the new owner carving out the mold to eliminate the name of the original glass house.

GI-120, which has a somewhat similar form, has the words “ASHTON” (on the Liberty side) and “HOUGH” (on the eagle side). Research by the McKearins as well as Kenneth Wilson has not yielded any information as to whether “Hough-Ashton” (or Ashton-Hough) referred to a manufacturer or retailer.

GI-121 and GI-122, although containing similar motifs to the above flasks, have the more oval shape discussed above. GI-121 has the initials “B&W” in script below the eagle, whereas GI-122 has no such initials. As with “Hough-Ashton” listed above, the origin and meaning of “B&W” in currently unknown.

Summary

There is certainly no shortage of wonderful flasks available to collectors, whether they are beginners, intermediate, or advanced. In previous articles, I discussed some categories of flasks that appeal to all collectors, regardless of how long they’ve collected. And the Columbia series certainly fits into that category, as these flasks are not only beautifully detailed, but also represent a very historical period in our history.

None of the Columbia flasks are considered common, and are rarely encountered at most bottle shows. Even the most common of the flasks, GI-117 and GI-121, in the most common aquamarine color, is difficult to locate, and expensive when encountered. And some of these flasks are nearly unique in certain colorations. Obviously, when you combine rarity with desirability, the result is a high price – so you require pretty deep pockets in order to build a large collection of Columbia flasks.