by Ken Previtali

24 October 2017

In reading the Saving the Fizz post, a number of things came to mind. Keeping CO2 bubbles sealed in a bottle until they were set free to tickle the senses was indeed a challenge to the burgeoning 19th century bottling industry. Why was fizz so important? Mainly because the sensation is what attracted their customers: No fizz? Less bizz!

In reading the Saving the Fizz post, a number of things came to mind. Keeping CO2 bubbles sealed in a bottle until they were set free to tickle the senses was indeed a challenge to the burgeoning 19th century bottling industry. Why was fizz so important? Mainly because the sensation is what attracted their customers: No fizz? Less bizz!

As Mr. Jones outlines in his enticing prose describing his book Saving the Fizz, the challenge drove inventors, glasshouses, and bottlers to try just about every way imaginable to make a reliable seal. In David Graci’s own groundbreaking 2003 book Soda and Beer Closures- 1850-1910, he notes that “Many of these bottle closure ideas appeared in a short period of time, competing fiercely for patronage of bottlers and customers alike. Those making it to a successful acceptance might be quickly bypassed by another, seemingly better idea. Patented bottle closures filed and recorded within the Patent Records seemed to herald a quickening impatience to discover this holy grail.” (David told me that he “had the pleasure of working with David (Jones) on both his massive books.”)

For every one thing we think we know, there are ten more we don’t, and that is especially true with history. Let’s go on another historical ramble on fizz with a “slight” slant towards ginger ale.

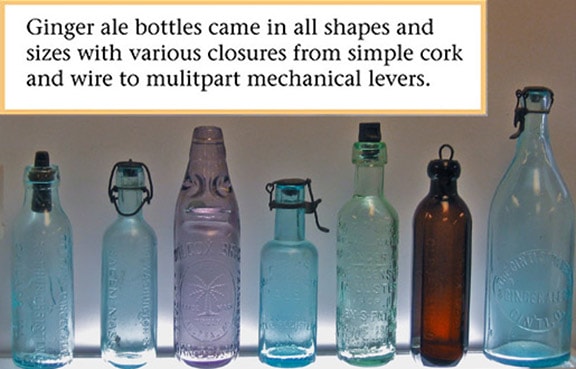

From 2013 FOHBC Manchester National Antique Bottle Show ginger ale display: Left to right, (patent holder, date, and bottler): A. Christin – 1875, Christin, Chicago, C. de Quillfeldt – 1875, S.B. Winn, Salem, MA, H. Codd – 1873, Wilcox Bros, Lilydale, Dandenong & Frankston, Australia, A. Rich – 1882, G.D. Dow, Boston, F. Riley – 1885, Grattan, Belfast, IR, C. Hutchinson- 1879, Geo. Schmuck, Cleveland, OH, F. Thatcher- 1885, Cincinnati Sodawater & Ginger Ale, OH.

Read: Ginger Ale Bottles / Go Withs

When just a cork and wire were the predominant method to seal a bottle, bottles were sometimes embossed with directions to “keep lying down.” The objective was to keep the liquid contents in contact with the cork to prevent shrinking. A dry cork allowed the zing to slip away unnoticed until an eager customer was disappointed by the stillness. And flat ginger ale is never very appealing; back then, or today.

Attributed to Josiah Russell, a successful London bottler who set up a factory in Rotterdam, Netherlands in 1887. While this example is embossed London, it is not known if this bottle was used in Rotterdam, but it is reported that Russell did make ginger ale at that location. Regardless which side of the channel it was, Russell wanted everyone to keep that cork moist.

Found more often, labels provided similar instructions.

This Mt. Vernon, Indiana bottler’s label ca. 1881 was very specific with instructions to customers. Even taking steps to retain the fizz after opening was important.

The instructions on this bottle ca. 1890 also recommend storing in a cool place. Relative to fizz, this was a good idea for several reasons. First, lower temperatures kept the CO2 from expanding, which prevented added pressure on the cork; lessening the chance of inadvertent “escape.” Also, CO2 is more soluble in liquid when kept cool, which helps retain fizz for a longer period of time.

Even though this is a machine-made crown top bottle from the1920s, the label still recommends storing lying down. These instructions probably were just a precaution left over from the days of leaky closure contraptions, as the simple crown cork seal was indeed the “holy grail” bottlers were chasing all those years. When the metal crown cap was crimped on, the thin wafer of cork made the seal, and it just didn’t leak. (Unless it was applied improperly by the bottler.)

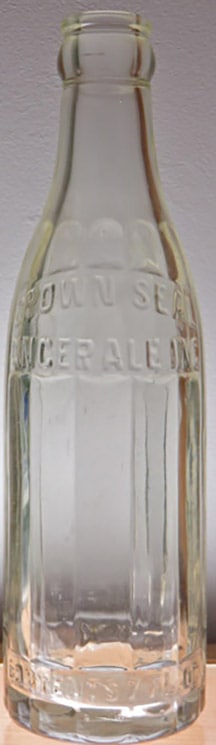

Crown Seal Ginger Ale, Inc, Troy, NY, ca. 1930 The importance of a safe, hygienic bottle seal was not lost on the soda consumer. Competition among bottlers was intense, especially during the prohibition era. It appears this Troy, NY bottler chose to attract customers by naming the entire company after the closure: “Crown Seal Ginger Ale, Inc.” Whether or not the name on this art deco bottle was an infringement on Crown, Cork & Seal’s copyrights is undetermined, but it seems a savvy marketing idea.

We learned from Mr. Jones that the inside screw stopper had been around for a while with Henry Barrett generally accepted as the inventor (1878) with a nod to several earlier others including the little-known Amasa Stone (1861). But then along came Frederick Riley of England in 1885 with his own twist on the screw stopper. In the closures section (http://www.sodasandbeers.com/SABBottleClosuresSoda.htm) of Sodas & Beer Bottles of North America, Tod von Mechow tells us that “Riley improved the inside screw stopper by adding a protrusion to the top of the stopper that allowed for easier opening.”

Grattan & Co. Belfast IR, claimed to be the original makers of ginger ale, but no one as yet has come forward with any solid proof to dislodge Cantrell, also of Belfast, as the chemist who started it all in 1852. (Then again, who lets facts get in the way of a good story?)

There are a lot of bottles with patent information embossed, but few can compare with Grattan’s declaration that in all of Ulster County, Ireland only they can use Riley’s patent extended stopper. That claim is probably easier to prove than their one about ginger ale.

Grattan put so many words on their bottle you can’t take them all in without rotating the bottle in your hand, or taking three pictures! The last line of embossing on the heel of the bottle was too small and run together to get a legible rubbing. It reads: “Riley Manfg. Co. London, S.W.”

While Grattan had cornered the market for Riley’s in their patch, others were using it elsewhere.

Hay & Son, Aberdeen, Scotland, ca.1900s. This firm was established in 1844 and lasted until 2001. The Hays politely asked for the return of the stopper with the bottle. One account of the business relates that “all sorts of strange fluids were often stored in bottles before they were returned for their deposit money, hence the need to sniff the black moulded screw tops.”

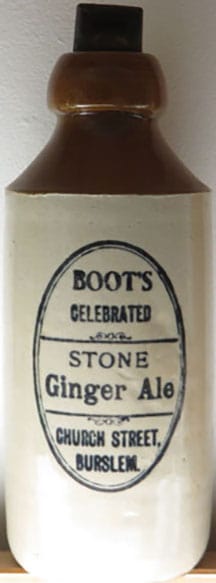

This stoneware screw top from Burslem, England is stenciled “ginger ale”, but may well have been a ginger beer. Ginger beer, a three- or four-times removed cousin of ginger ale, did not have a high volume of carbonation, and could be bottled in stoneware. Most stoneware bottles couldn’t take the pressure of the “forced air” in soda water; particularly ginger ale which traditionally had to have a strong zing of bubbles. Perhaps some of our friends across the pond can tell us if this one is really a ginger beer and should be given the boot from my list of ginger ales.

Given Mr. Jones hails from down under, we need to take a closer look at the Wilcox Bros. Codd bottle. The Wilcoxes operated in three locations Lilydale, Dandenong and Frankston, each 30-40 km from Melbourne. Today those towns are the “suburbs” of Melbourne, but in the 1900s they were in the “country”, but not too far away by Australian standards. The tree fern “trademark” and “Truly Australian” reflects national pride, as the tree fern Cyathea cooperi, is native to Australia. This sun-colored ginger ale example is a fairly rare bottle.

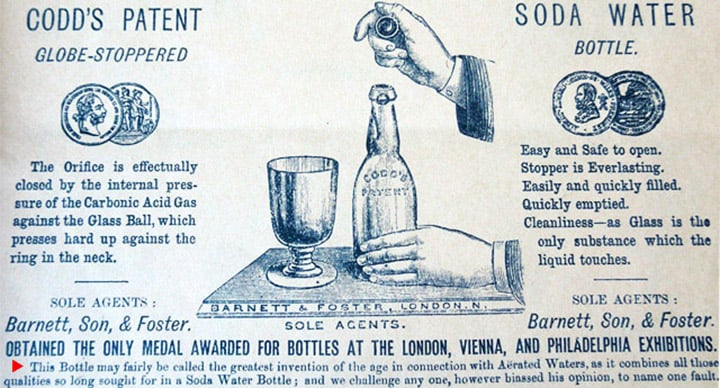

This ad from 1878 touts the benefits of the Codd bottle as perhaps the finally-found “holy grail” of closures.

“The bottle may fairly be called the greatest invention of the age in connection with Aerated Waters, as it combines all those qualities so long sought for in a Soda Water Bottle; and we challenge any one, however biassed his opinion, to name one fault.”

Of course, we have the benefit of hindsight to observe that while they believed that at the time, it was not to become the ultimate solution as advertised.

If you didn’t have one of these, was using your thumb the alternative? The Home Brewery, established in 1875, became a massive company owning 100s of pubs around the Nottingham, England region, where they sold vast amounts of beer and ale. Apparently they did make ginger ale, but this wooden Codd bottle “opener” is the only reference to that activity, so far.

To complete the Australian connection, here’s a nod to Mr. Jones who perhaps deserves to earn a blue ribbon for his Save the Fizz; my only Sydney ginger ale bottle.

We began this ramble talking about how early bottlers fervently sought the best way to contain that tickling zing of bubbles. No matter what; bright, crisp carbonation continued to be what the customers wanted: Soda water ain’t got a thing without that zing!

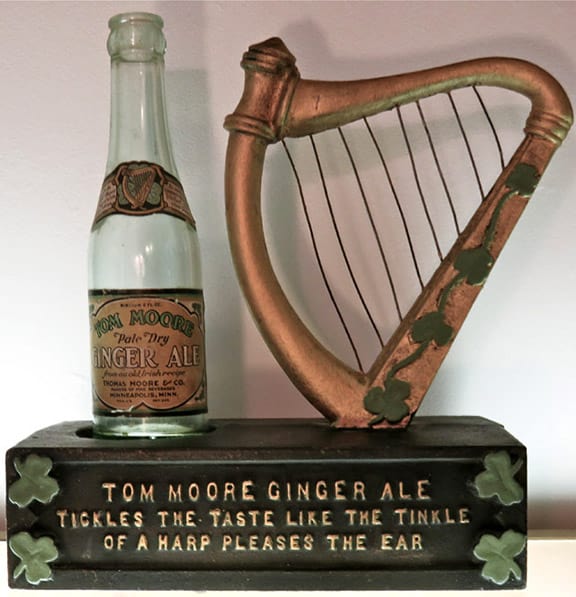

One of best descriptions of the fugitive fizz is by bottler Tom Moore of Minneapolis, MN.