Looking at some of the Bitters Bottles on the steamboat Bertrand Part 2

14 September 2012

T H E

B E R T R A N D B I T T E R S B O T T L E S

In part 2 of the Steamboat Bertrand series we will look at the bitters bottles such at the Hostetter‘s Stomach Bitters, Drake’s Plantation Bitters, Kelly’s Old Cabin Bitters and Schroeder’s Stomach Bitters found in the recovery and excavation efforts. (Read First: Looking at some of the Bitters Bottles on the steamboat Bertrand – Part 1)

In part 2 of the Steamboat Bertrand series we will look at the bitters bottles such at the Hostetter‘s Stomach Bitters, Drake’s Plantation Bitters, Kelly’s Old Cabin Bitters and Schroeder’s Stomach Bitters found in the recovery and excavation efforts. (Read First: Looking at some of the Bitters Bottles on the steamboat Bertrand – Part 1)

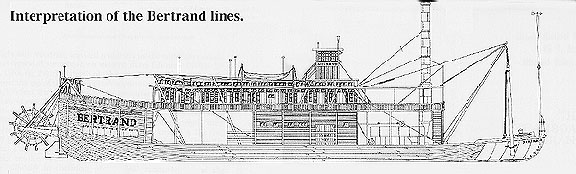

The steamboat Bertrand, carrying cargo up the Missouri River to Virginia City, Montana Territory, sank on April 1, 1865, after hitting a snag in the river north of Omaha, Nebraska.

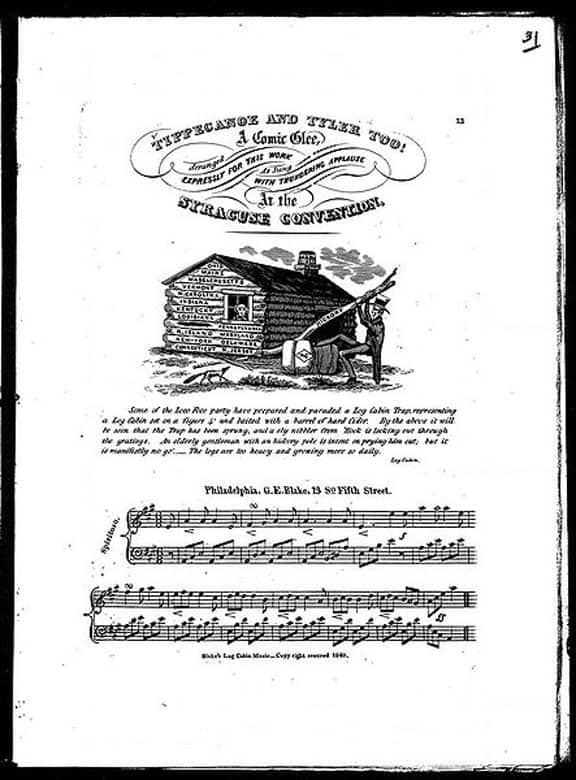

J.C. Penny said that salesmanship is an art. Aside from P.T. Barnum, one would be hard pressed to find a more aggressive marketer than Patrick Henry Drake. In 1861, he formed a partnership with Demas S. Barnes, of New York City. Barnes was the largest wholesale drug dealer in New York City, and his list of occupations include, banker, newspaper publisher, real estate developer and in 1867, he was elected to the 67th congressional district from Brooklyn. After the war, Barnes built an empire by buying the rights to other patent medicines.

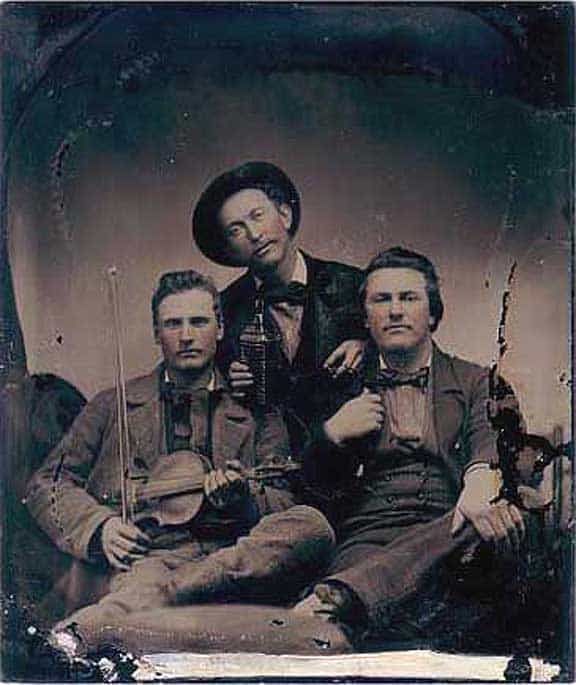

One can only picture these three gentlemen enjoying their bottle of Drake’s Plantation Bitters that was carried up on the steamship Bertrand to Virginia City, Montana Territory.

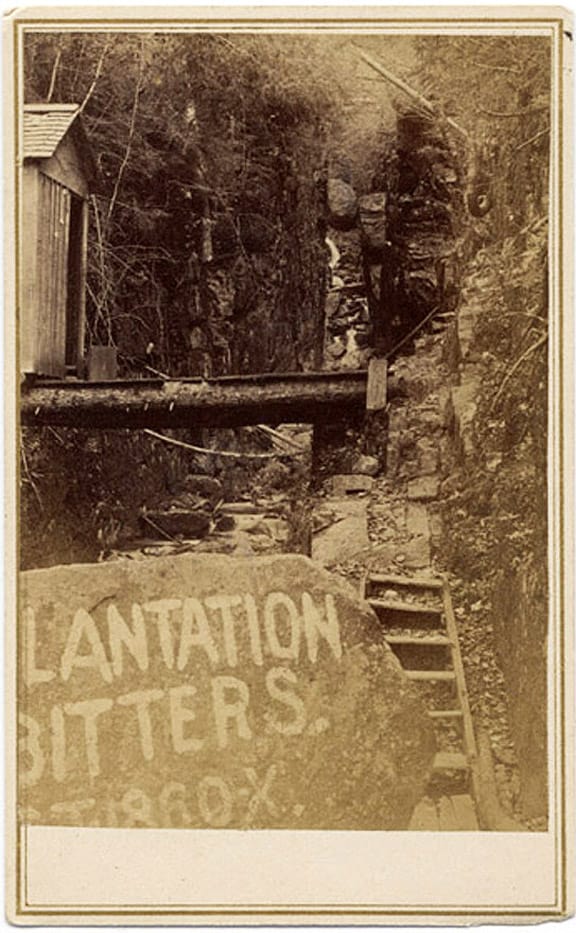

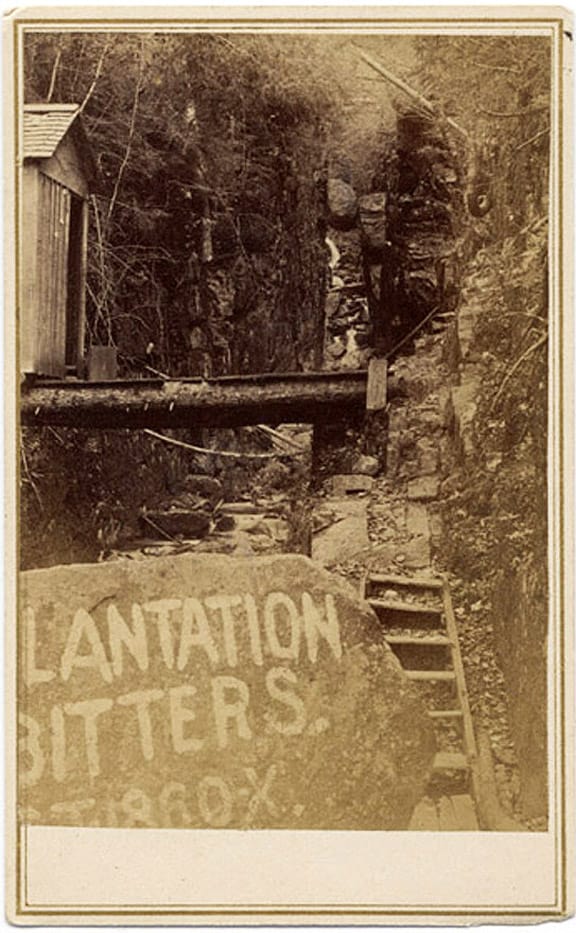

Drake obtained a patent for his bottle design in 1862, using the log cabin theme of his bottle design to characterize the Plantation Bitters he produced. Calling himself Colonel Drake, he was an aggressive self promoter, and included advertising signs, in every crate shipped to retailers. The crates salvaged from the riverboat Bertrand contained gilded glass signs promoting his bitters. He had his slogan S.T. 1860 X, painted on rocks, fences and sides of barns. He advertised in about any newspaper that sold space, and had even unsuccessfully tried to have his S.T. 1860 X slogan painted on Niagara Falls, Mount Ararat and even the pyramids in Egypt. The cryptic slogan really locked the product into the mind of the public, bringing speculation as to its meaning.

Drake had his slogan S.T. 1860 X, painted on rocks, fences and sides of barns. He advertised in about any newspaper that sold space, and had even unsuccessfully tried to have his S.T. 1860 X slogan painted on Niagara Falls, Mount Ararat and even the pyramids in Egypt.

It was widely held that it meant Started Trade in 1860 with $10, but he later explained it in his post war almanacs Morning Noon and Night. “It represents St. Croix—S.T. being the conventional equivalent of Saint, and 1-8-6-0 standing for the letters C-R-O-I, and so forming, with the concluding X, the word CROIX. Nothing can be more simple, or, it may be, more appropriate. St. Croix Rum is a stimulating basis of the Plantation Bitters, and it is, therefore in accordance with the fitness of things, that St. Croix should be the basis of their business shibboleth.” [N.J. Sekela]

Read More: Information on the Drake’s Plantation Bitters Variants

Read More: What is an Arabesque Drakes Plantation Bitters

Read More: Drakes Plantation Bitters – Encased Postage

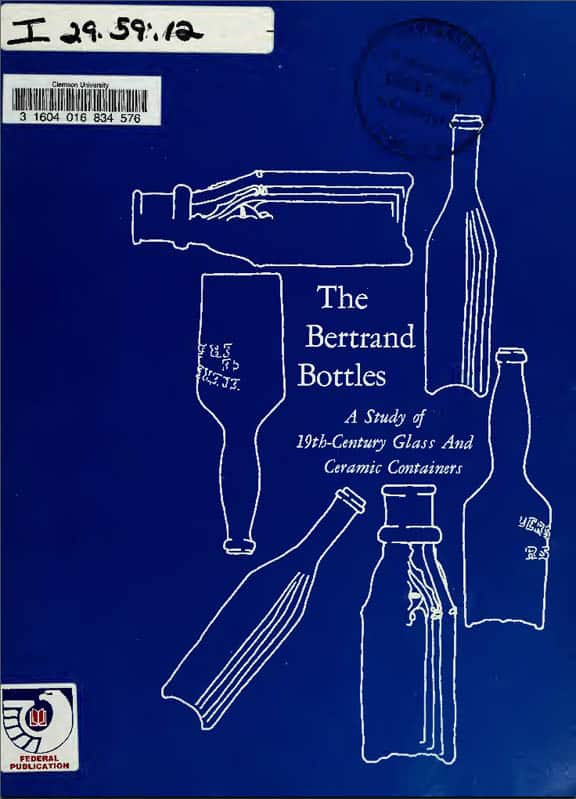

The Bertrand Bottles

A Study of 19th-Century Glass and Ceramic Containers

by Ronald R. Switzer

This book pictured below, published by the National Park Service (Department of Interior) in 1974 is one of the classic works in the field of historic archaeology as it pertains to bottles. I thoroughly enjoyed it and have pulled and highlighted some areas of interest relating to bitters bottles.

Some of the bitters bottles and related material recovered and inventoried at the DeSoto National Wildlife Refuge include:

Hostetter‘s Stomach Bitters

Dr. Jacob & David Hostetter. Of greater fame in the mid-19th century was Dr. Jacob Hostetter and his son David. Dr. Hostetter was a prominent Pennsylvania physician who, for a number of years, had prescribed a tonic of his own formulation for his patients. In 1853 David Hostetter adopted his father’s prized prescription to concoct the famous “Hostetter Stomachic Bitters.” The tonic was sold successfully under the trademark “Hostetter & Smith,” registered under numbers 3, 135, 223 and 8,970 in the United States Patent Office between July 4, 1859, and December, 1884, when the trademark was changed to “Hostetter & Co.” This same trademark, which incorporated the use of specific labels, was declared again on August 9, 1888 and was registered as Number 15,873 by the United States Patent Office on September 18, 1888. Between 1889 and 1920, the Hostetter Company was selling bitters all over the world, backed by an advertising campaign that cost $4,425,000 in the 30-year period. Most of the advertising took the form of regularly published almanacs.

The product contained 25 percent alcohol by volume, but this presumably was used only to extract the medicinal virtues of the plant materials it contained. The alcohol was also regarded as a solvent and preservative. The other active natural and synthetic ingredients the “Hostetter” formulation contained, and the volume in which they were present per fluid ounce, appear in an undated advertisement from the Hostetter Corporation (personal communication, A. B. Adams, Vice-president of the Hostetter Company). Cited in the Adams statement are listed below:

Cinchona bark (Cinchona succirubra) 15.00 grains

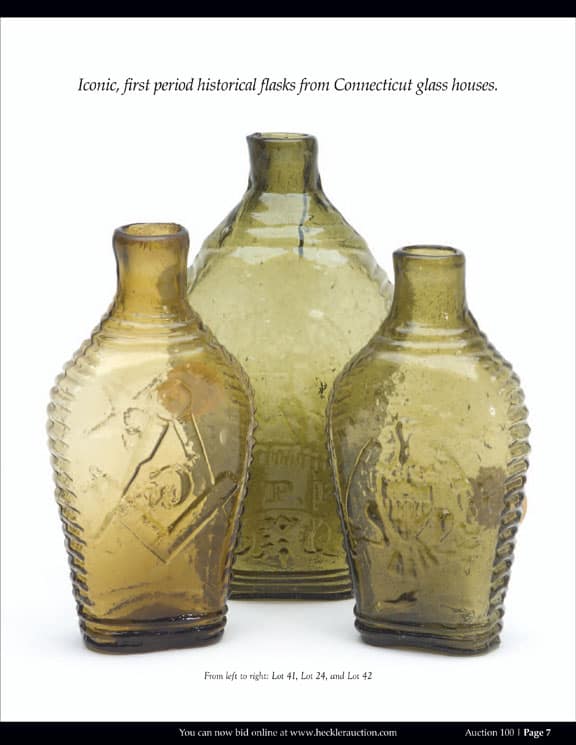

Centuary plant (Erythraeacentarium) 0.65 grains

Anise fruit (Pimpinellaanisum) 0.65 grains

Serpentaria Roots (Artistolocha serpentaria) 3.00 grains

Yerba Santa Leaves (Eriodictyoncalifornicum) 2.00 grains

Calamus rhizomes (Acorus calamus) 2.00 grains

Culver’s Roots (Veronica virginica) 0.42 grains

Ginger rhizomes (Zingiber officinale) 1.00 grains

Nux Vomica seed (Strychmos Nux vomica) 8.00 m.

Glycerine 5 %

Sugar not to exceed 20.00 grains

Saccharin 1/15 grain

Oil of Orange 0.5 m.

Nux vomica or strychnine is readily identifiable as a poisonous, colorless, crystalline alkaloid which is used in small doses as a stimulant to the nervous system. Cinchona bark is a bitter alkaloid with various medicinal properties; from it quinine is extracted. Anise is a small white or yellow flowered plant of the carrot family whose seed is used primarily as a flavoring, while calamus, sometimes called “sweet flag” is a palm-like plant. The purpose of the latter in the formula is not known. Ginger, of course, is a tropical herb whose rootstalk is used as a flavoring and in medicines. The other ingredients need no explanation.

Regardless of the ingredients, even teetotalers found stimulation in the cure-all, and it became exceedingly popular both in the North and the South prior to the Civil War. The South Carolina Banner of May 6, 1858, printed in Abbeville, contained the following Hostetter‘s advertisement:

A wine-glass full of these Bitters taken three times a day, will be a sure cure for Dyspepsia, will remove all flatulency; assist digestion; give a good appetite, and impart a healthy tone to the whole system, and is a certain preventive of fever and ague. Children, delicate ladies, or persons in a debilitated state should try a bottle.

The U.S. Army abolished the liquor ration for troops in 1832. When the Civil War began, Hostetter and other makers of patent medicines urged their products on the Federal government for use by the military. Hostetter deplored the use of common whiskey by officers in the field, believing that his concoction of bitters was better for their health and morals (Carson, 1961, p. 49; Lord, 1969, p. 52). His advice on the subject of bitters was doubtless followed with enthusiasm by northern soldiers, a condition which more than made up for the loss of most of his southern market.

When alcohol was allocated during World War I, Hostetter and Company suffered severe financial difficulties from which it never fully recovered. However, in 1902 Hostetter was listed as one of 3,045 certified millionaires in the United States, and is said to have made something in excess of $18 million from his celebrated tonic (Carson, 1961, pp. 42, 73).

In 1959 the State Pharmacal Company of Newark, New Jersey, a wholly owned division of Hazel Bishop Incorporated, Union, New Jersey, purchased the trademark and business of Dr. Hostetter‘s Stomachic Bitters. The trademark is still owned by that firm and is listed by the United States Patent Office under Serial Number 76,604, filed June 26, 1959 and registered May 24, I960 (No. 698,028); the product is no longer made.

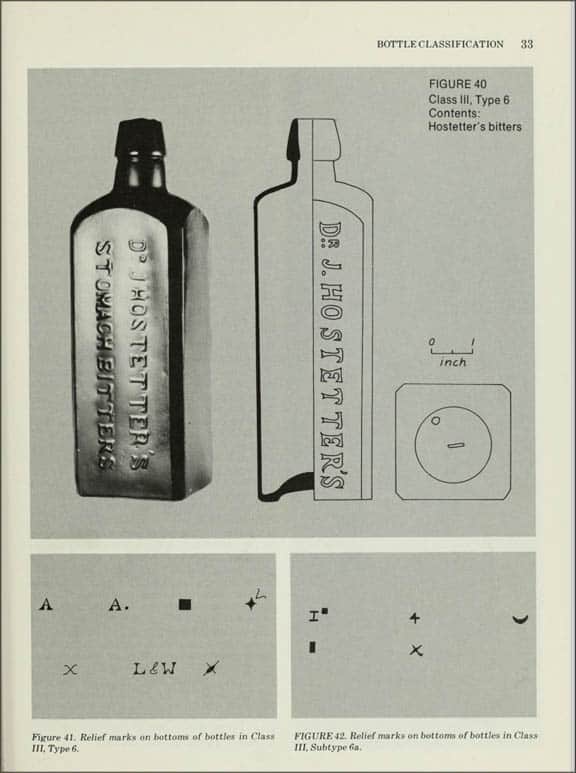

The Bertrand Hostetter’s – Class III, Type 6, Subtypes 6a, 6b, 6c, 6d, 6e, 6f:

The dark amber and dark green Hostetter‘s bitters bottles represent the largest single category of bottles with alcoholic contents. One hundred and ninety-one, 12-bottle cases of Hostetter‘s bitters in two sizes of bottles have been counted in the collection. The average alcohol content is 27 percent by volume, which is somewhat greater than the original Hostetter formula.

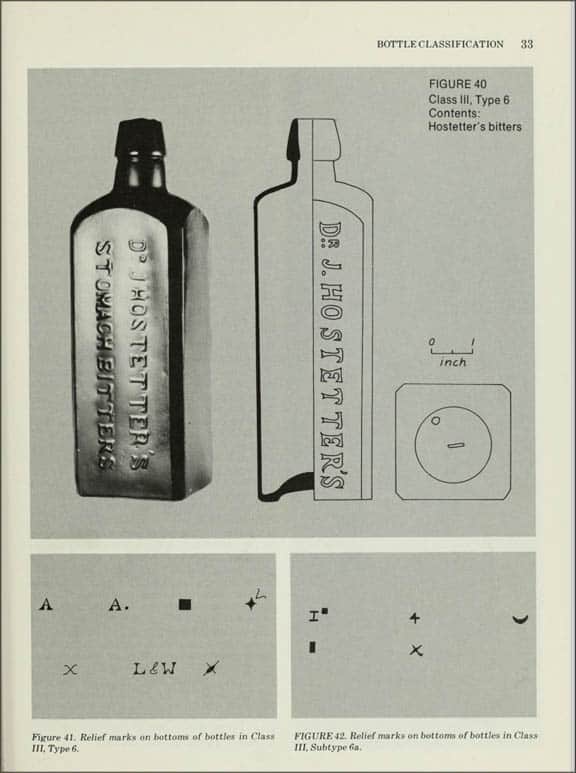

The small, amber, 22-ounce bottles in Type 6 were blown in two-piece molds and have slanting collar neck finishes (fig. 40). Bottle bases are flat and exhibit shallow dish-shaped depressions at the centers. Some of the bases have relief marks. Apparently, the “L&W” mark should be attributed to the Lorenz and Wightman firm who operated the Pittsburgh Glass Works.

Type 6 bottles are embossed on one side with the inscription:

“DR. J. HOSTETTER’S / STOMACH BITTERS,” and were stoppered with corks. The bottles also display fragments of paper labels on two sides. These are described below with Subtype 6a. Dimensions, Type 6: height, 8 7/8 inches; base, 2 5/8 by 2 5/8 inches; diameter of neck (outside), 1 1/8 inches, (inside), 3/4 in.

Bitters bottles in the Subtype 6a category are dark green or amber in color and are similar morphologically to Type 6 except that they have a greater capacity of about 28 ounces.

The bottles contain cork stoppers, covered with thick foil seals. Over the tops of the seals. A dark blue paper label with gold (now gray) print was affixed to one side of a bottle and the opposing side displayed a label with black print on a white background. The upper half of the black and white label depicts St. George slaying the dragon. Dimensions, Subtype 6a: height, 9 5/16 inches; base, 2 3/16 by 2 3/16 inches; diameter of neck (outside), 1 1/16 inch, (inside), 3/4 inch.

One of the gold-lettered blue paper labels, reconstructed from several fragments, reads as follows: HOSTETTER’S CELEBRATED STOMACH BITTERS

One wine-glassful taken three times a day before meals, will be a swift and certain cure for Dyspepsia, Liver Complaint, and every species of indigestion – an unfailing remedy for Intermittent Fever, Fever and Ague, and all kinds of periodical flux, Colics, and Choleric maladies – a cure for costiveness – a mild and safe invigorant and corroborant for delicate females – a good, anti-bilious, alternative and tonic preparation for ordinary family purposes – a powerful recuperant after the frame has been reduced and altered by sickness – an excellent appetizer as well as a strengthener of the blood and other fluids desirable as a corrective and mild cathartic and an agreeable and wholesome stimulant. Persons in a debilitated state should commence by taking small doses and increase with their strength.

One group of eight large plain Hostetter‘s bottles were recovered with four embossed specimens in a crate marked:

“HOSTETTERS / STOMACH / BITTERS / BARSTORES / BERTRAND.” The dark green and amber bottles, designated as Subtype 6b have no raised letters on their sides, but otherwise they are like the bottles in Subtype 6a. Dimensions, Subtype 6b: height, 9 3/4 inches; base, 2 7/8 by 2 7/8 inches; diameter of neck (outside), 1 1/16 inch, (inside), sealed.

Larger Hostetter‘s bottles are definitely in the minority, and, at this writing, no more than two cases have been found. Perhaps others will come to our attention as work progresses in opening the crates.

Wooden Hostetter’s cases bear metal straps at the corners, and the boxes are marked in black stenciling in the following manner:

“HOSTETTER & SMITH / SOLE / MANUFACTURERS / &/ PROPRIETORS / PITTSBURGH, P. A.”; consignee: “VIVIAN & SIMPSON / VIRGINIA CITY, M.T..” Inside many of the cases were eight almanacs packed in sets of two, or twelve almanacs packed in four sets of three. Over the almanacs large folded Hostetter broadsides had been placed, one per box. The broadsides are lettered in bold reddish-brown print, and at the center of each is a woodcut in black of St. George slaying the dragon. Unfortunately, not one complete broadside has been recovered. Fragments pieced together in the Bertrand Conservation Laboratory indicate that they measured 18 by 24 1/2 inches.

Four of my HOSTETTER’S STOMACH BITTERS, each different color and mold – Meyer Collection

Drake’s Plantation Bitters

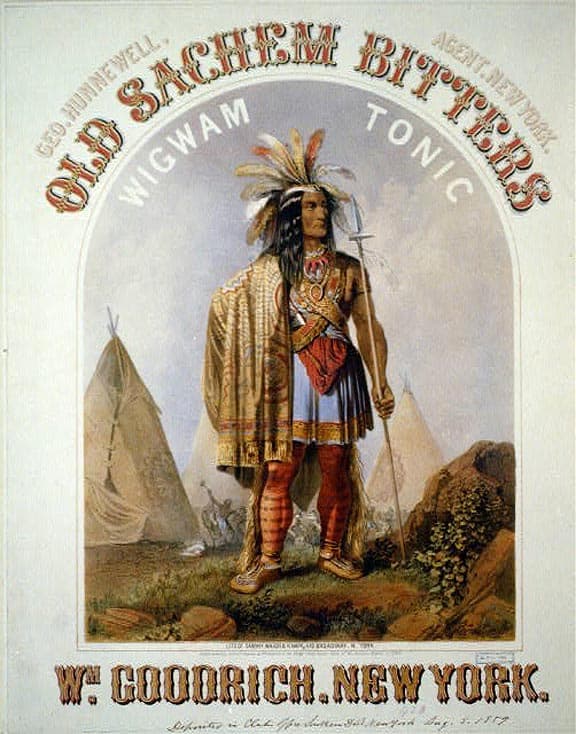

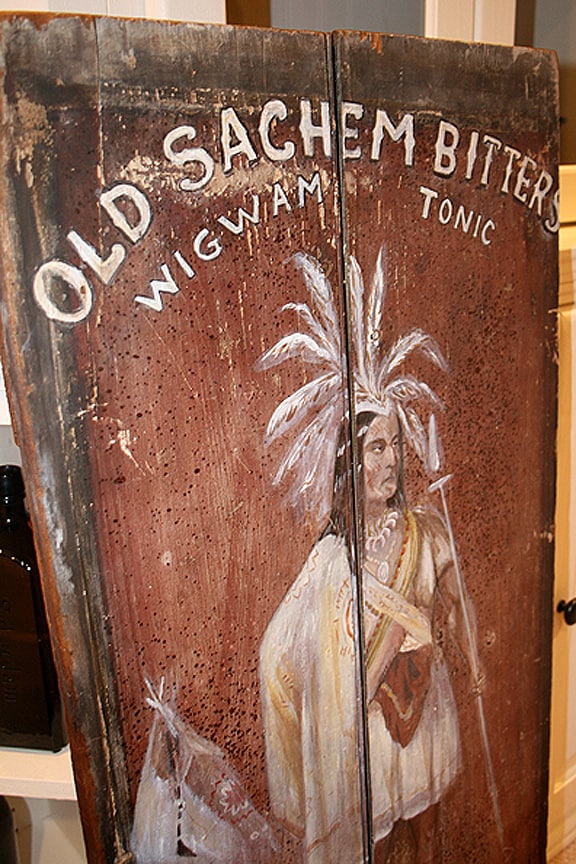

Another famous name in proprietary medicines of the 1860’s and represented in the Bertrand cargo is that of Colonel P. H. Drake. If Colonel Drake’s Plantation Bitters looked and tasted like whiskey, it was because it was just that, or, more specifically, St. Croix rum (Carson, 1961, p. 45). This “nutritious” essence, which was derived from sugar cane and bittered with barks and herbs, made its appearance during the Civil War when there was a high excise tax on whiskey.

Colonel Drake is said to have spent a great deal of money on advertising and went to great lengths to promote his product. His mysterious advertising jargon containing the letters and figures “S. T. 1860 X” appeared on fences, barns, billboards and rocks around the world. Drake, as some historians have it, even tried to paint his slogan on Mount Ararat, Niagara Falls, and on the famous Egyptian pyramids, but he was unsuccessful in all three ventures (Carson, 1961, pp. 42, 92).

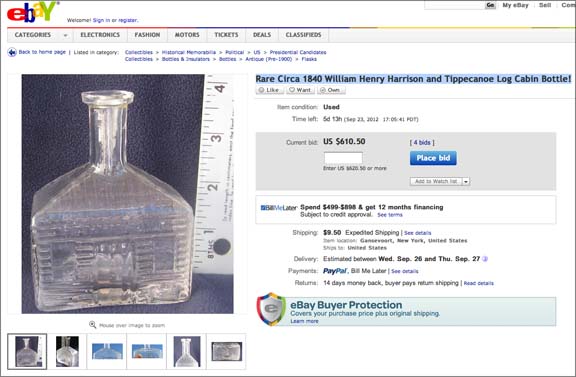

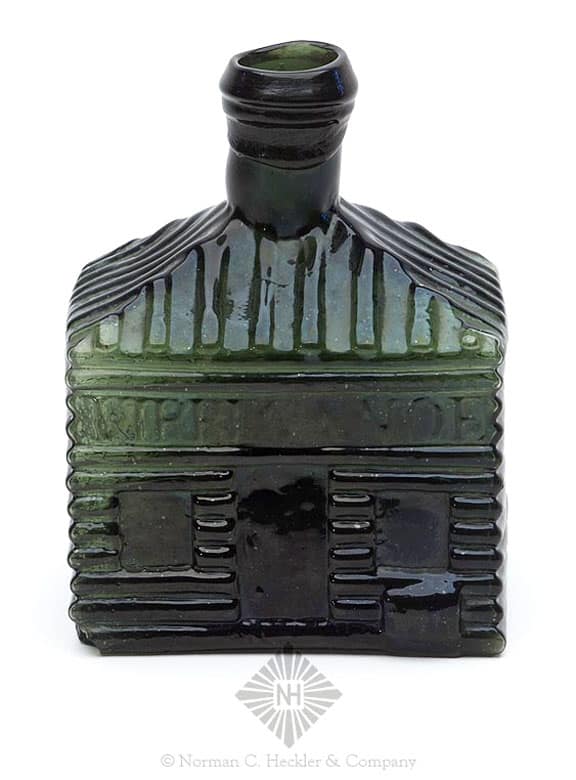

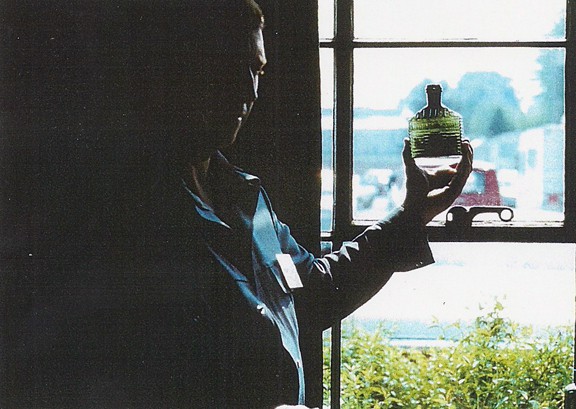

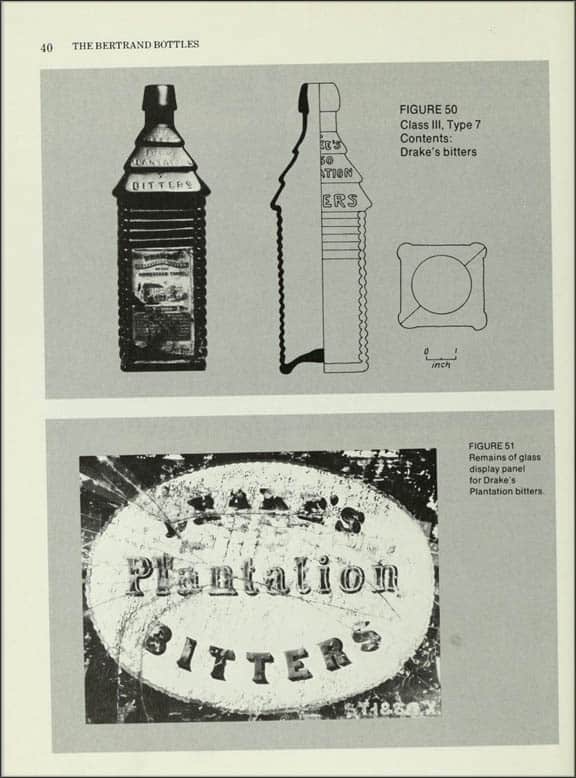

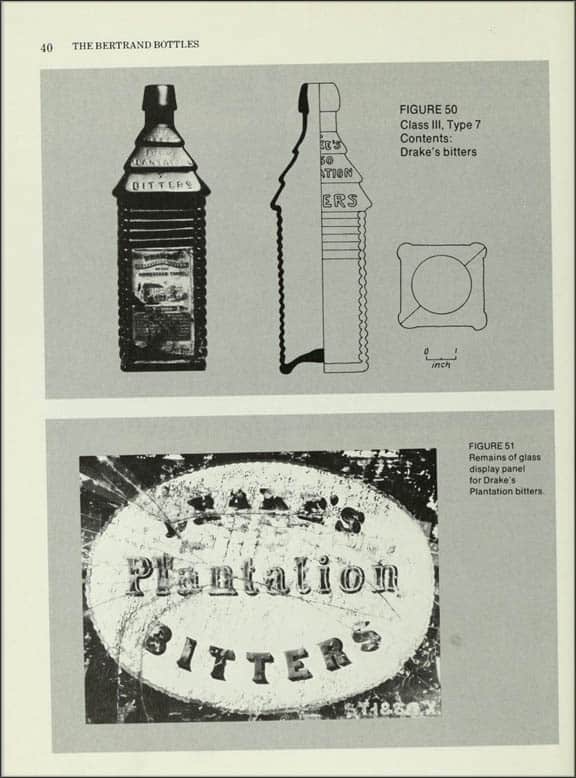

The Bertrand Plantation Bottles – Class III, Type 7:

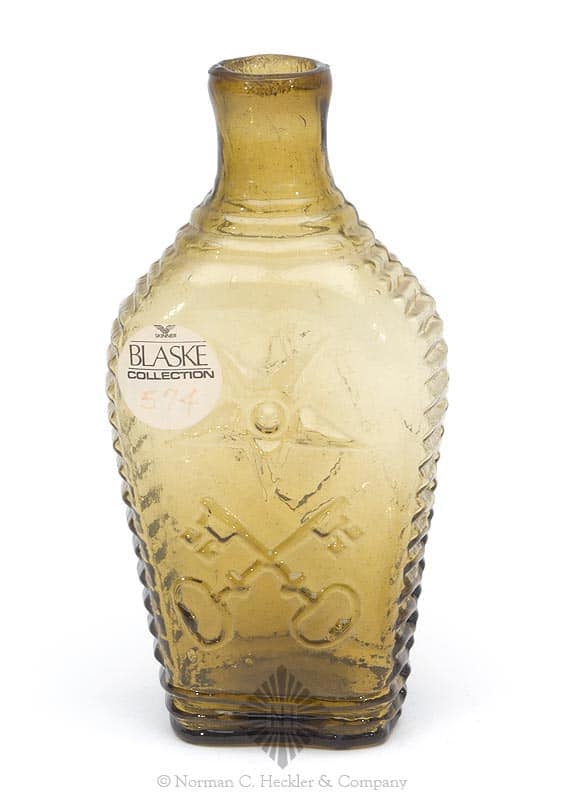

To Type 7 have been assigned 109 nearly square, amber-colored, cabin-shaped bottles containing Drake’s Plantation Bitters and an additional number of fragments. The 24 bottles tested contain nearly 17 percent alcohol. The front and reverse sides of the bottles have six relief logs above plain panels which accomondated paper labels. The tiered roof shoulder on the front side is embossed with letters on all three tiers as follows: top:

“S T / DRAKES”; middle: “1860 / PLANTATION”; bottom: “X / BITTERS.” The middle tier of the reverse side is embossed: “PATENTED / 1862.” The two remaining sides are molded to represent logs, which cross at the corners of the bottles, and the tiered roof above is corrugated. The necks are cylindrical and terminate in slanting collar finishes. On each bottle the edge of the base is flat and the center of the base bears a plain dished depression. All of these speci-mens were stoppered with corks.

In many instances fragments of black-on-white paper labels were found adhering to the front and back panels. Some bottles show evidence of having been wrapped in a black and-white printed paper wrapper bearing testimony of the effectiveness of the tonic.

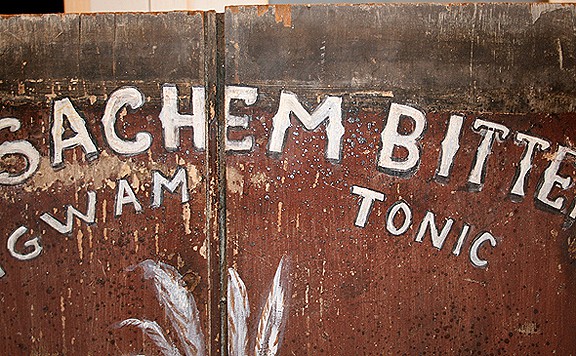

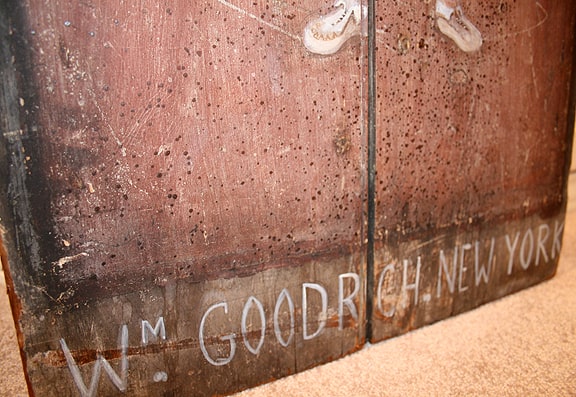

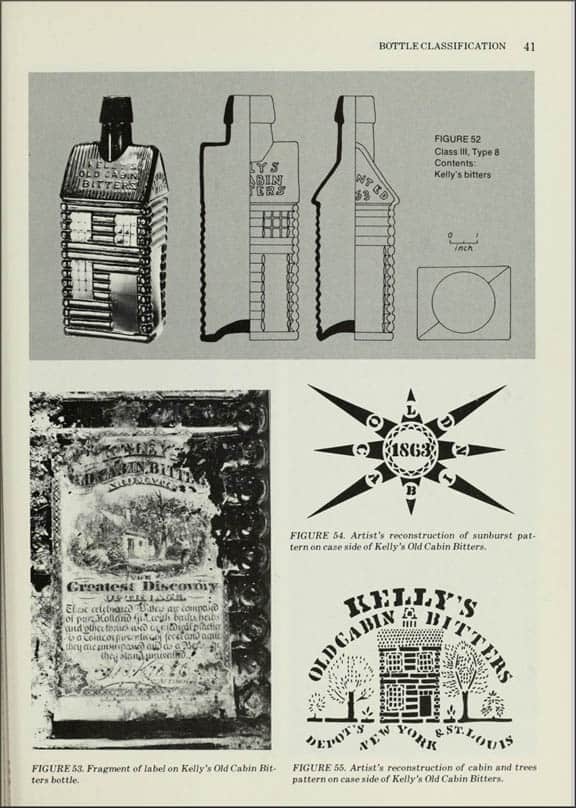

Wooden shipping cases for Drake’s Plantation Bitters are unusual in that the lids of several exhibit single strength glass display panels or advertisements attached to the inner side. Each sign is composed with a black border surrounding a large white oval trimmed with gold. The central oval is lettered in three different letter styles; the top

line of letters are in gold outlined in black, the middle line of letters in red outlined in gold and black, and the bottom line in gold letters outlined in black. The cases bear the following stenciled marks on the exteriors:

“DRAKE’S PLANTATION BITTERS / DEPOT NEW YORK,” or “S T 1860 X / G / G T & S / WITH CARE VIA SARNIA”; consignees: “WORDEN & CO / HELL GATE, M.T.,” or “VIVIAN & SIMPSON / VIRGINIA CITY, M.T.” Dimensions, Type 7: height, 9 7/8 inches; base, 2 3/4 by 2 3/4 inches; diameter of neck (outside), 1 1/16 inches, (inside), 13/16 inch.

6-log DRAKE’S PLANTATION BITTERS – Meyer Collection

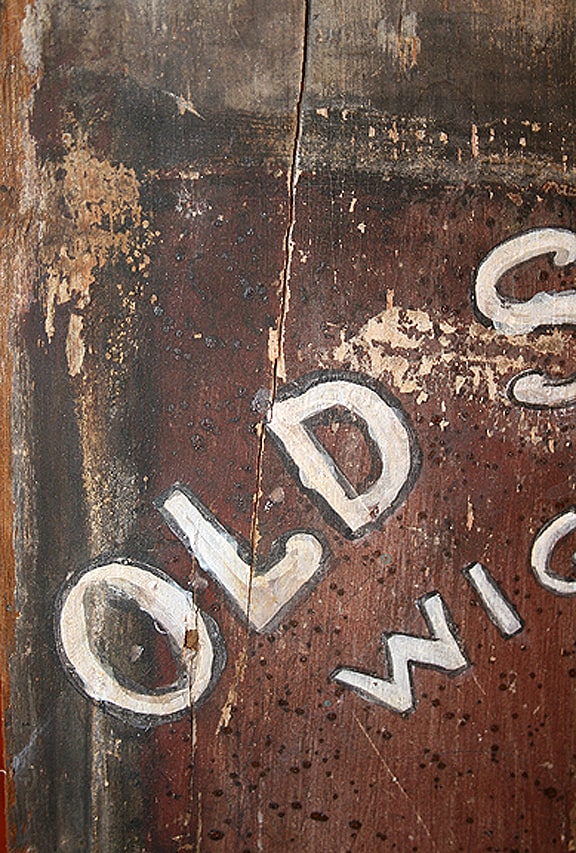

Kelly’s Old Cabin Bitters

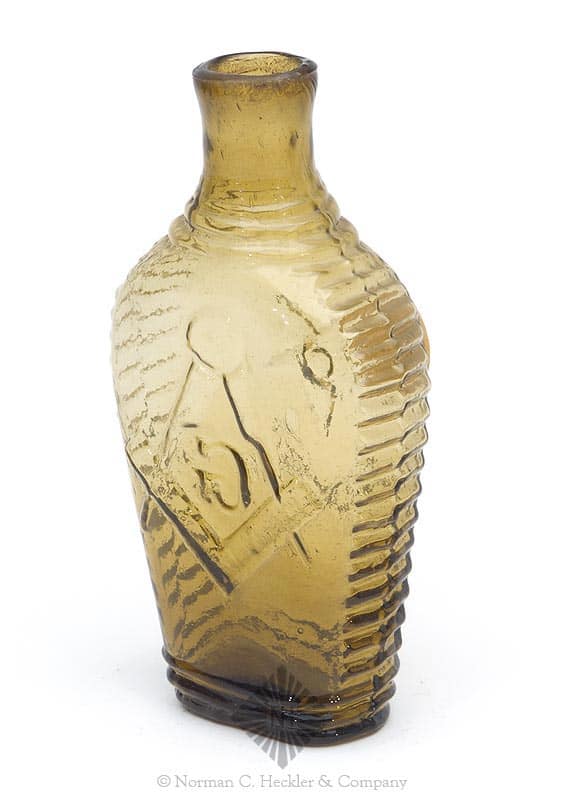

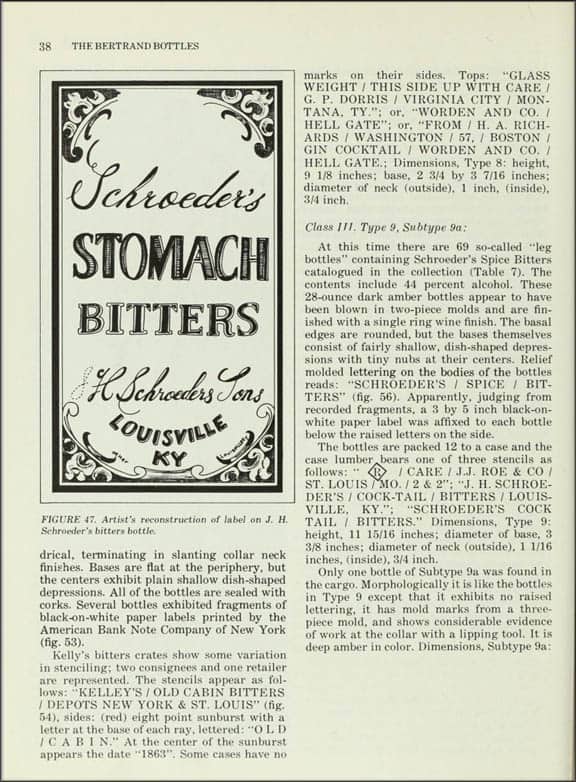

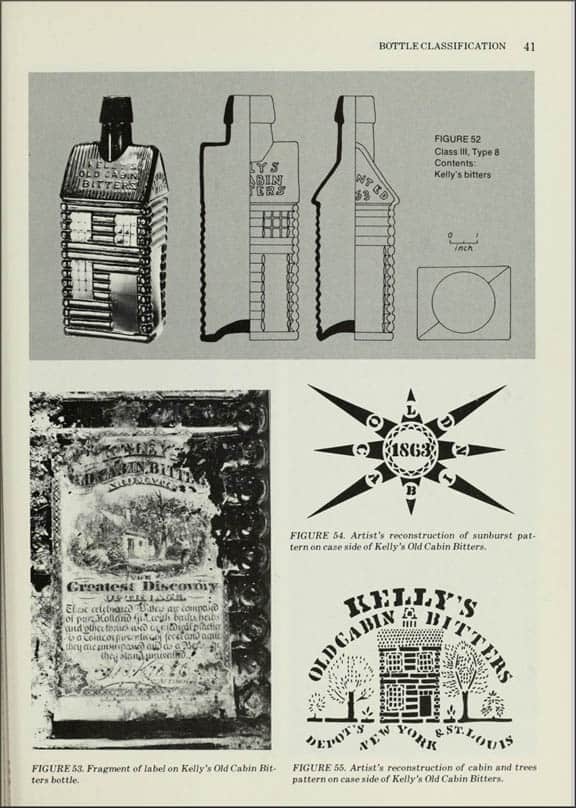

The Bertrand Kelly’s Bottles – Class III, Type 8:

All bottles in this type contain 25 ounces of 23 proof Kelly’s Old Cabin Bitters and are molded to represent log cabins. The front and back sides bear three mold-impressed windows and a door. Corrugated roof panels which form the shoulders on the front

and back are embossed:

“KELLYS / OLD CABIN / BITTERS.” The remaining two

sides bear plain panels for labels, topped with five relief logs and a triangular-shaped space under the pitch of the roof embossed: “PATENTED / 1863.” The bottle necks are cylindrical.

Kelly’s bitters crates show some variation in stenciling; two consignees and one retailer are represented. The stencils appear as follows:

“KELLEY’S / OLD CABIN BITTERS / DEPOTS NEW YORK & ST. LOUIS”, sides: (red) eight point sunburst with a letter at the base of each ray, lettered: “O L D / C A B I N.” At the center of the sunburst appears the date “1863”. Some cases have no marks on their sides. Tops: “GLASS WEIGHT / THIS SIDE UP WITH CARE / G. P. DORRIS / VIRGINIA CITY / MONTANA, TY.”; or,

“WORDEN AND CO. / HELL GATE”; or, “FROM / H. A. RICHARDS / WASHINGTON / 57, / BOSTON / GIN COCKTAIL / WORDEN AND CO. / HELL GATE.; Dimensions, Type 8: height, 9 1/8 inches; base, 2 3/4 by 3 7/16 inches; diameter of neck (outside), 1 inch, (inside), 3/4 inch.

KELLY’S OLD CABIN BITTERS – Meyer Collection

Schroeder’s Stomach Bitters

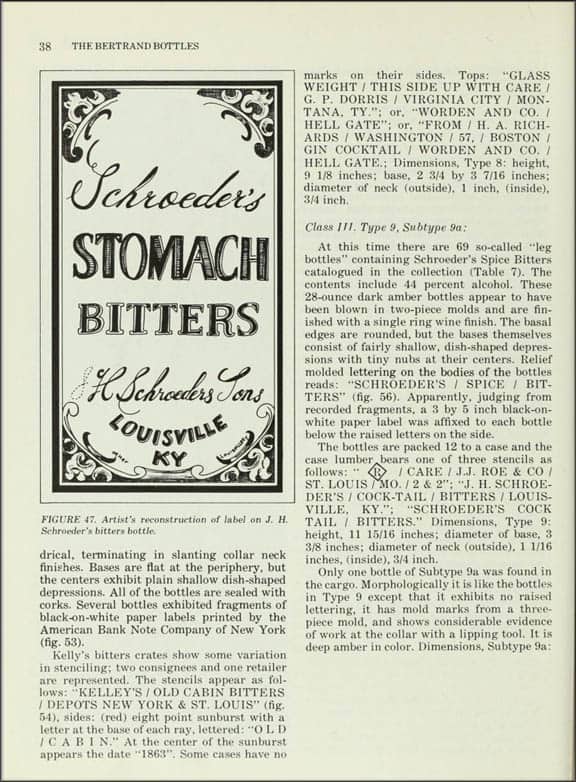

Not a great deal is known about J. H. Schroeder, other than the fact that he produced bitters, probably made with catawba wine. He was a dealer in wines, liquors and general bar stores. The Louisville Business Mirror for 1858-1859 (p. 281) includes an advertisement for the Schroeder business. Louisville printed no directories during the Civil War, but by 1864 the firm was again listed on Wall Street as “J. H. Schroeder and Son.” In 1865 the business moved to Main Street, Louisville (Martin F. Schmidt., Louisville Free Public Library, personal communication, 1971).

Neither the Schroeder’s Spice Bitters nor the Schroeder’s Stomach Bitters bottles in the Bertrand cargo were embossed on the bases with letters, but presumably they were products of the Kentucky Glass Works Company of Louisville. The firm was established in 1849 by Taylor, Stanger, Ramsey and Company and was sold the following year to George L. Douglass and James Taylor (McKearin and McKearin, 1971, p. 606; Toulouse, 1971, p. 323). The factory produced vials, demijohns and bottles of other kinds, including some made in private molds. By 1855 the factory had been purchased by Douglas, Rutherford & Company, and the name had been changed to Louisville Glass Works. Ownership of the Louisville Works changed again in 1856 and 1865 and thereafter about every two years until it closed in 1873. However, according to Toulouse (1971, p. 324) the shop was purchased and reopened that same year by Captain J. B. Ford, who operated it as the Louisville Kentucky Glass Works until about 1886.

There is no way to determine exactly when the Schroeder’s bottles on the Bertrand were made. Between 1849 and 1855 the company used the marks “K Y G W,” but it may have used others, including “KY G W Co,” about which we have no information. By 1870, if not eariler, their bottles were marked “L G W” to reflect the change in the company name in 1855. Inasmuch as the firm did considerable business in bottles made in private molds it is not unreasonable to assume the Schroeder’s Spice Bitters bottles and the “French square” Schroeder’s Stomach Bitters bottles are two such products.

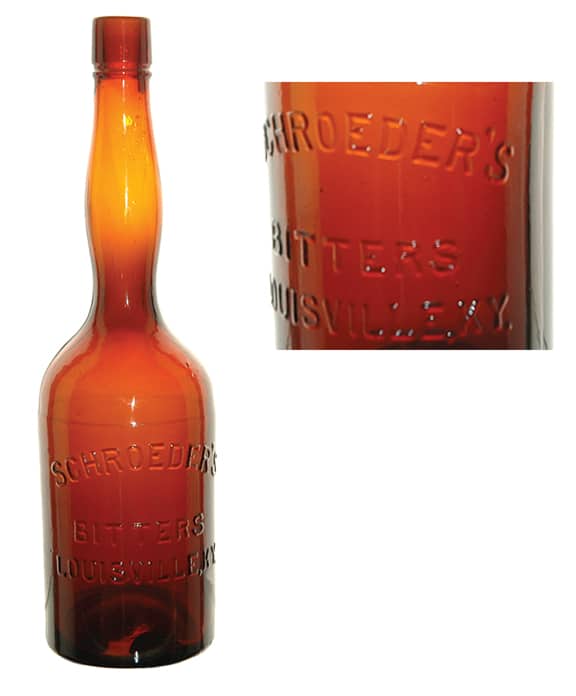

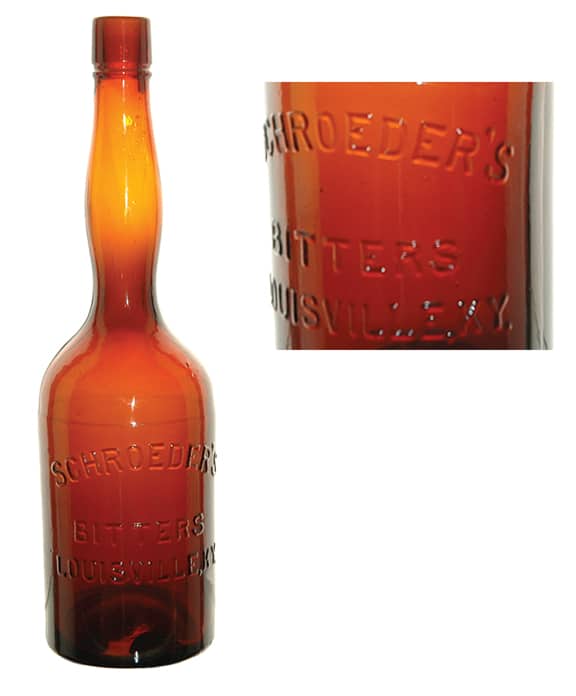

Apparently the Bertrand specimens differ from the usual run of Schroeder’s bottles in some other respects. Sold in quarts and pints, the “leg” shaped bottles are most commonly lettered on one side:

“SCHROEDER’S / BITTERS / LOUISVILLE, KY.” The Bertrand examples are lettered “SCHROEDER’S SPICE /BITTERS.”

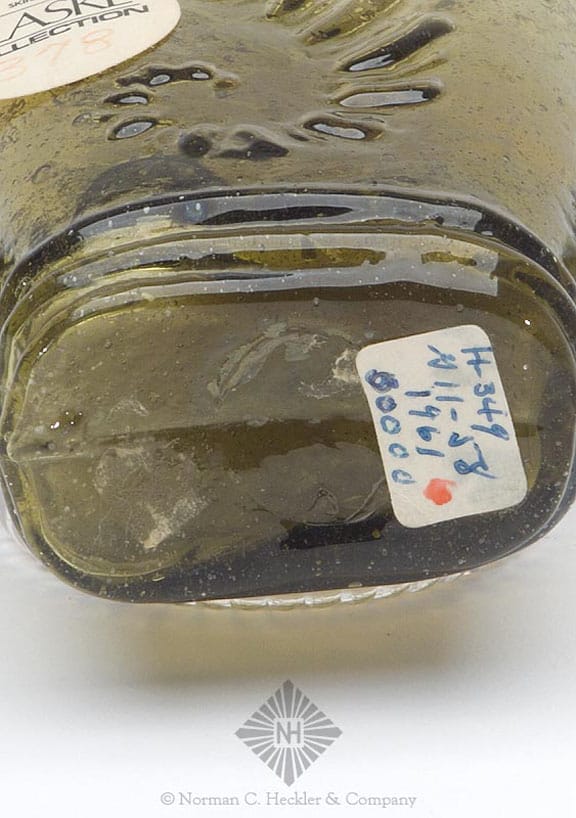

At this time there are 69 so-called “leg bottles” containing Schroeder’s Spice Bitters catalogued in the collection. The contents include 44 percent alcohol. These 28-ounce dark amber bottles appear to have been blown in two-piece molds and are finished with a single ring wine finish. The basal edges are rounded, but the bases themselves consist of fairly shallow, dish-shaped depressions with tiny nubs at their centers. Relief molded lettering on the bodies of the bottles reads:

“SCHROEDER’S / SPICE / BITTERS”. Apparently, judging from recorded fragments, a 3 by 5 inch black-on-white paper label was affixed to each bottle below the raised letters on the side.

The bottles are packed 12 to a case and the case lumber bears one of three stencils as follows:

“/ CARE / J.J. ROE & CO / ST. LOUIS MO. / 2 & 2”; “J. H. SCHROEDER’S / COCKTAIL / BITTERS / LOUISVILLE, KY.”; “SCHROEDER’S COCKTAIL / BITTERS.” Dimensions, Type 9: height, 11 15/16 inches; diameter of base, 3 3/8 inches; diameter of neck (outside), 1 1/16 inches, (inside), 3/4 inch.

Only one bottle of Subtype 9a was found in the cargo. Morphologically it is like the bottles in Type 9 except that it exhibits no raised lettering, it has mold marks from a three-piece mold, and shows considerable evidence of work at the collar with a lipping tool. It is deep amber in color. Dimensions, Subtype 9a: height, 11 3/4 inches; diameter of base, 3 1/2 inches; diameter of neck (outside), 1 1/8 inches, (inside), 3/4 inch.

Eleven pewter dispenser caps for Schroeder’s bitters bottles have been identified in the Bertrand collection, only one of which was found in direct association with Schroeder’s bottles.

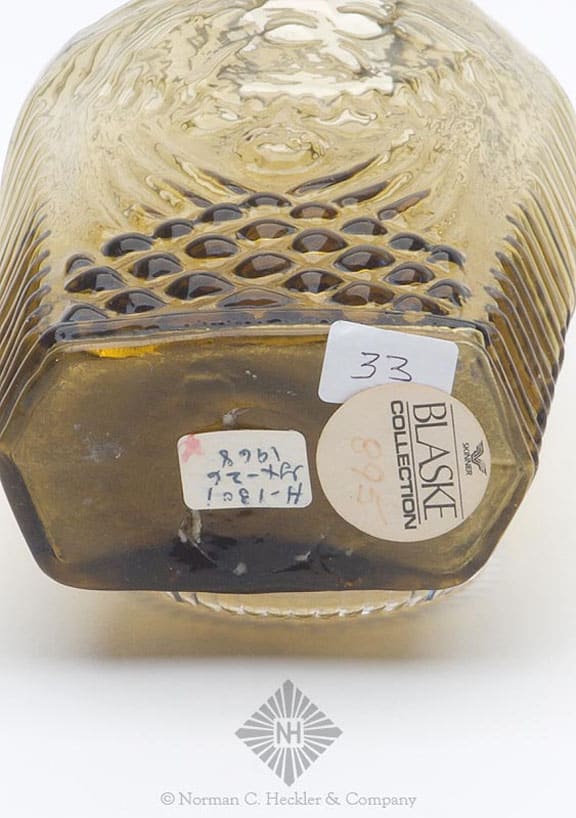

There are eight 32-ounce bottles of J. H. Schroeder’s Bitters in the Bertrand cargo and a number of fragments assigned to Subtype 6c. The contents of the whole bottles averaged 25 percent alcohol by volume. These olive green bottles were blown in two-piece molds and the slanted collar neck finish was applied with a lipping tool. The “French Square” bottles have beveled corners and are stoppered with corks, capped with red sealing wax or a tan colored putty-like substance. The edge of the base of each bottle is flat and the center bears a plain, shallow, circular dish-shaped depression. Three sides of the body are plain; the fourth bears the relief molded words

“J. H. SCHROEDER / 28 WALL STREET / LOUISVILLE, KY.” Dimensions, Subtype 6c: height, 9 15/16 inches; base, 3 1/16 by 3 1/16 inches; diameter of neck (outside), 1 inch, (inside), 3/4 inch.

One of my many different SCHROEDER’S BITTERS. This is a ladies leg figural. If you Have a SCHROEDER’S SPICE BITTERS call me! (not Jeff Burkhardt or Bill Taylor)