Dr. Whitney’s Bitters – Olean, New York

09 October 2014 (R•011119)

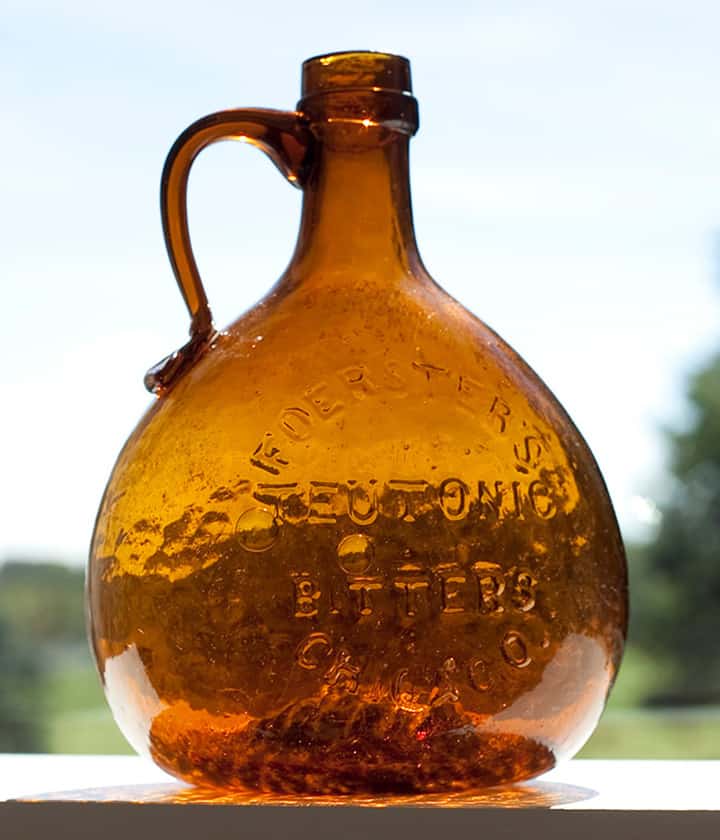

![]() New York collector, Mark Warne contacted me about a bitters bottle I was unfamiliar with. I just may add it to my collection! Mark was kind enough to send a few pictures. To this bitters collector, this is exciting news. The Dr. Whitney’s Bitters from Olean, New York is obviously a later bottle but how late? Were there earlier versions?

New York collector, Mark Warne contacted me about a bitters bottle I was unfamiliar with. I just may add it to my collection! Mark was kind enough to send a few pictures. To this bitters collector, this is exciting news. The Dr. Whitney’s Bitters from Olean, New York is obviously a later bottle but how late? Were there earlier versions?

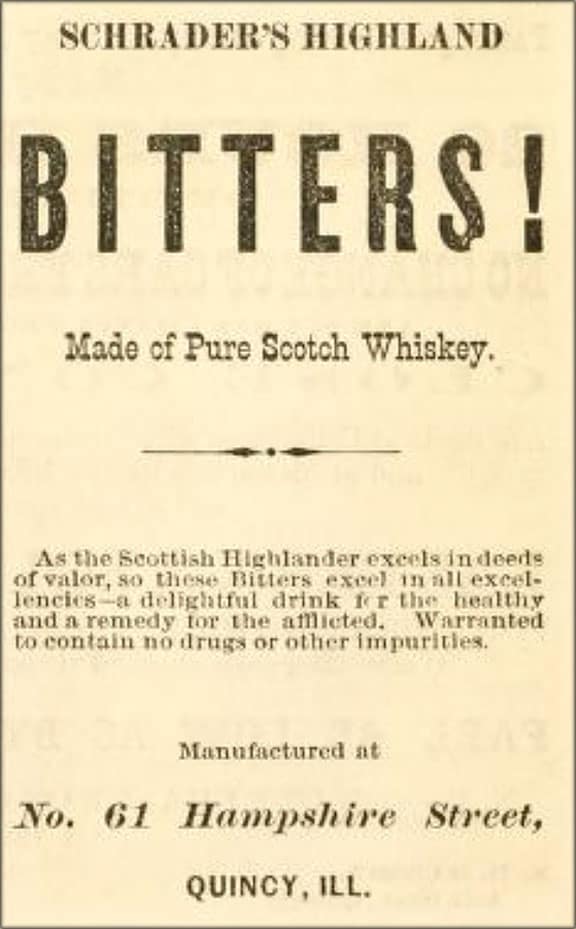

Checking it out in Bitters Bottles by Carlyn Ring and W.C. Ham, I see the following:

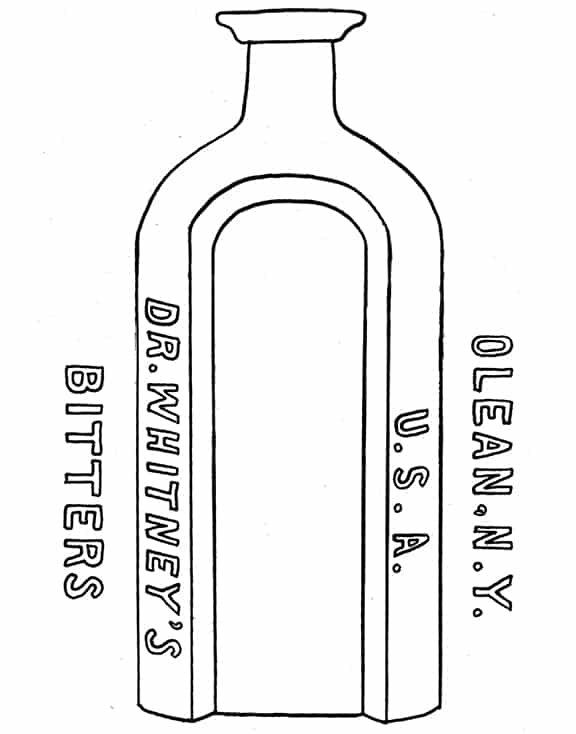

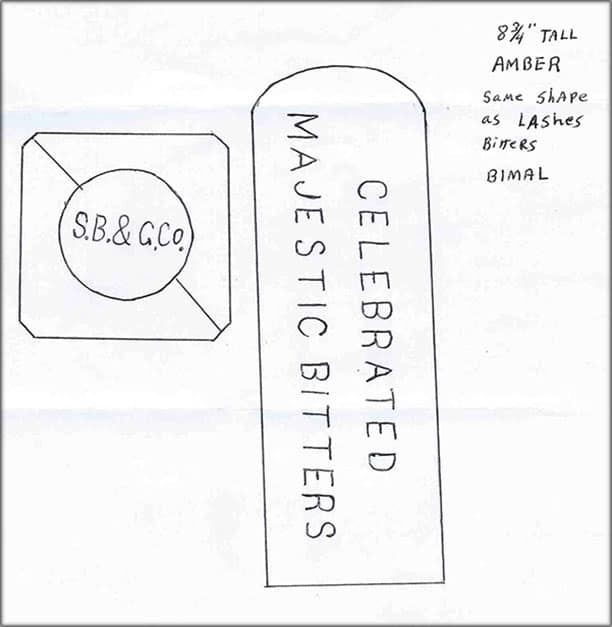

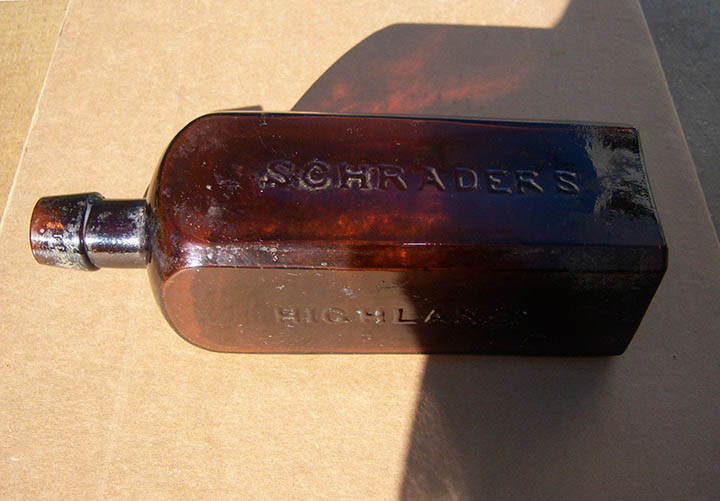

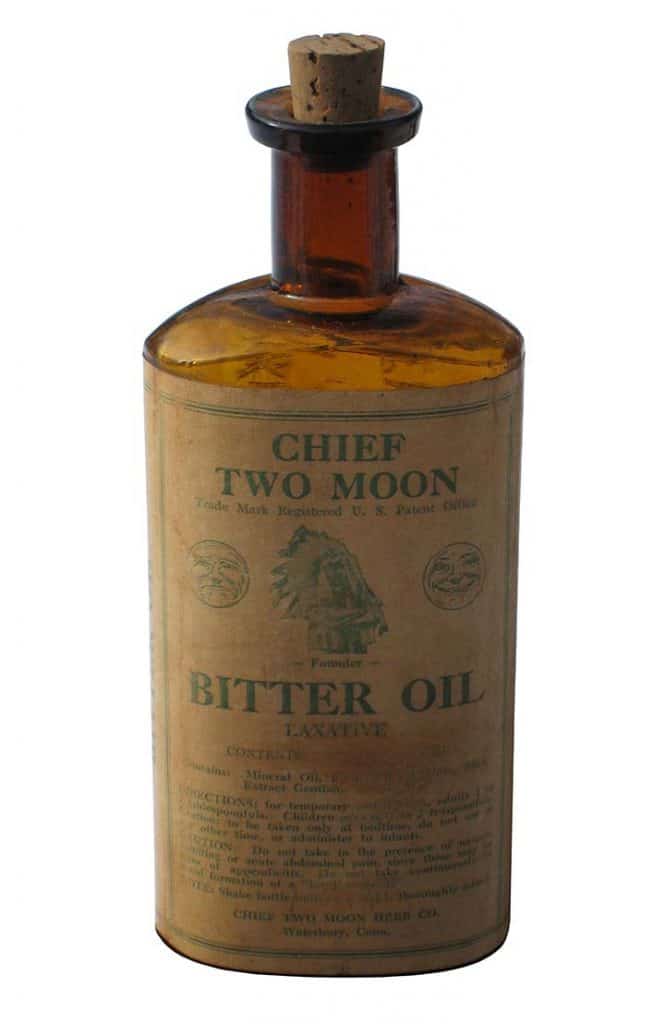

W 103 DR. WHITNEY’S BITTERS

U.S.A. / sp / DR. / WHITNEY’S // BITTERS / sp / OLEAN, N.Y. //

7 x 3 x 2 (5 3/8)

Oval, Amber, FM, Tooled lip, Extremely rare

Lettering vertical on either side of sunken panel.

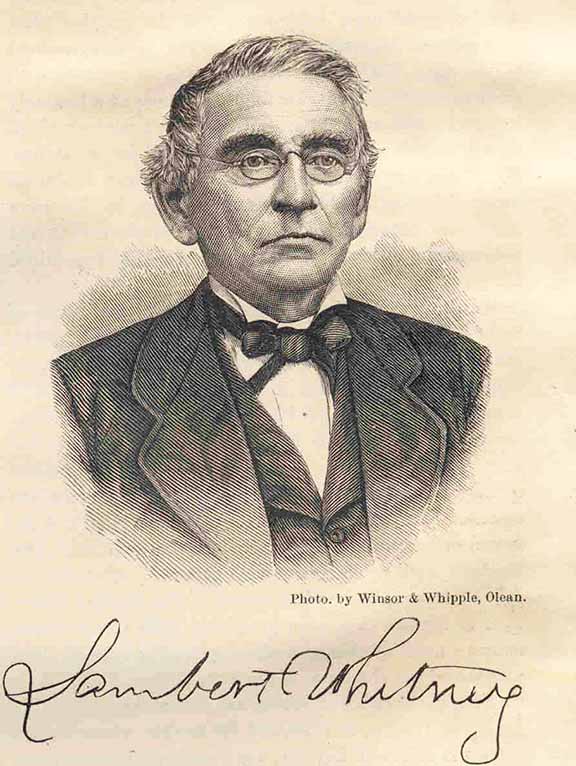

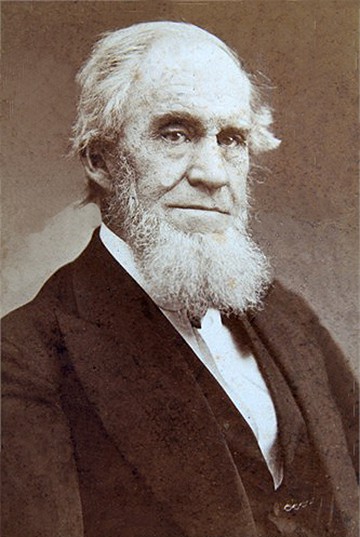

LAMBERT WHITNEY. M.D

Dr. Lambert Whitney, the namesake for this bitters bottle, had a long and storied career. I can’t pin down exactly when he made his bitters but I suspect it started in the early to mid 1860s based on the 1919 marketing statement, “These bitters have proved themselves good for over 50 years”. At first I thought his son Lambert S. Whitney carried the torch after his death but this is unlikely as he was in the wagon business big time and retired as a gentleman farmer.

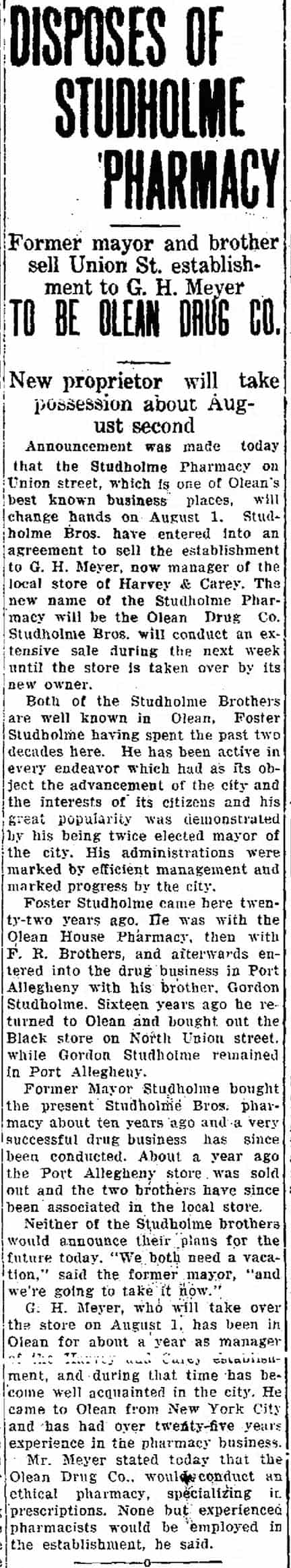

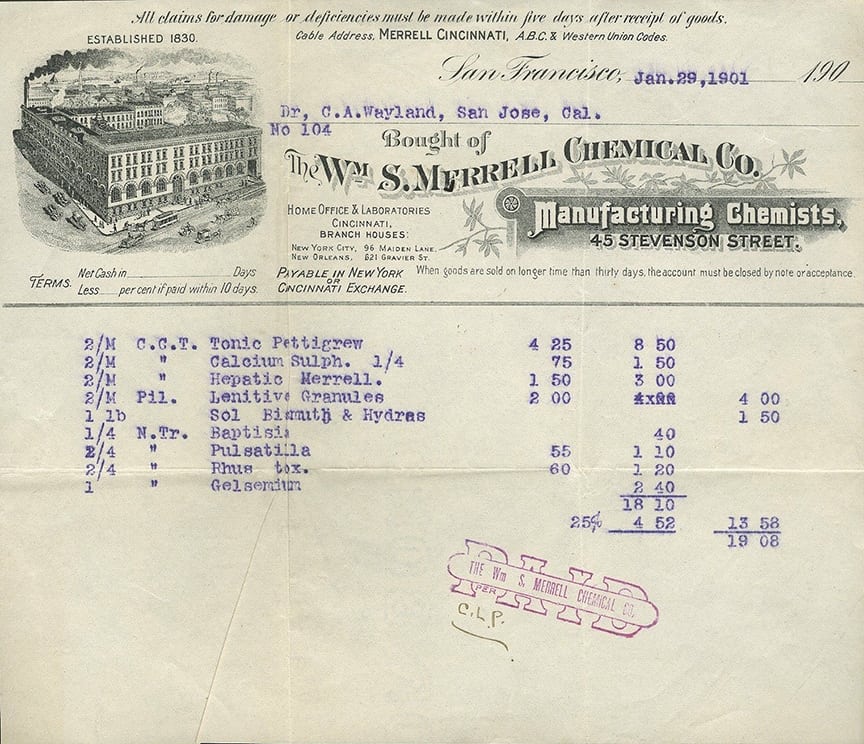

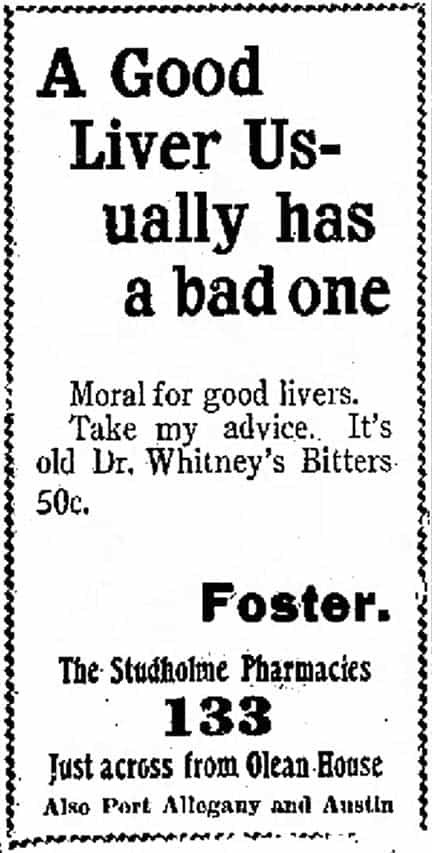

It is a mystery how these bitters survived after Doctor Lamberts death. If I had to bet, I would say that the Studholme brothers (Foster and Gordon Studholme), who had a prominent pharmacy in Olean, purchased the Dr. Whitney brand and sold the bitters. If the bitters was earlier it could have been associated with the Olean House Pharmacy or an earlier business. The last clipping in the post explains this relationship. Somewhere there is an earlier variant of this bottle with a lable. Gotta find it.

Foster Studholme of Studholme Brothers Pharmacy was selling Dr. Whitney’s Bitters. He was also Mayor of Olean from 1916 to 1919.

Lambert Whitney was born at St. Johnsbury, Vermont on October 10, 1812. After receiving his preliminary education at the public school of his native town, he commenced the study of medicine, and chose that as a profession, which he has successfully practiced for upwards of forty years. His parents moved to New Hampshire when he was a youth, and it was there he began the study of the profession he has so long honored. After an interval of five years in his studies, and in June, 1833, he removed to Olean and entered the office of Edward Finn, M.D., and subsequently completed his office studies under Dr. Andrew Mead, a prominent pioneer physician of this village, in the fall of 1836. He then went to Geneva and attended a course of medical lectures, and in January, 1837, he received his diploma from the New York State Medical Society. He immediately thereafter settled in Olean, and began an active and successful professional career. During the summer of 1837, Dr. Whitney became a member of the old Cattaraugus County Medical Society, and remained such as long as it retained its organization. He is also an honorary member of the present society.

In the early years of his practice Dr. Whitney rode horseback over a large territory. He says: “I did everything that a doctor then had to do.”

Historical gazetteer and biographical memorial of Cattaraugus County, N.Y

Dr. Lambert Whitney of Olean remembers when trips to Warren, Pittsburgh and Cincinnati were made by raft down the Allegheny River.

Cuba New York Patriot – December 2, 1897

In May, 1834, Dr. Whitney united in marriage with Miss Sallie Senter. They have had six children, five sons and one daughter, of whom three of the sons survive. Of these, L.S. (Lambert S. Whitney) and R.M. (Russell M. Whitney) were the founders of the Olean Hub Factory, and one, the younger son, James A. (James A. Whitney), is now a member of the firm of E.M. Jones & Co., of San Francisco, a long established and influential fancy goods and notion house of that city.

In 1834, Dr. Whitney received the appointment of deputy sheriff, and served in that capacity one term with satisfaction. In 1838 he was elected a justice of peace and served in that office in all, twelve years. In 1853 he was chosen to represent his town on the board of supervisors, and also occupied the same position the following year, owing to a tie vote between Warren Mills and J.L. Savage, the opposing candidates. In 1860 the people of Cattaraugus County, having confidence in the doctor’s integrity, elected him to the office of county treasurer, which responsible position he filled acceptably and well for three years. He now holds the offices of coroner of the county and of health officer of the corporation, the latter a position of great responsibility and considerable discretionary power, neither of which Dr. Whitney either neglects or abuses. He always sustains an independent deportment in the administration of official duties, and, being actuated by a desire to do the best possibly to do the best possibly for the taxpayers, they appreciate his worth, and insist on his retention in office.

In religion, Dr. Whitney is a Baptist, and for nearly half a century has been an active member of that denomination. His liberality in religious enterprises and his public spirited activity in secular concerns are alike commendable, and through these qualities, and by reason of his general worth as a citizen, neighbor, physician, and friend, he enjoys a prominent position in the community, and the esteem and respect of all to whom he is known. – HISTORY OF CATTARAUGUS COUNTY, NEW YORK, Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of its Prominent Men and Pioneers. Philadelphia:

L.H. Everts, 1879, Edited by Franklin Ellis

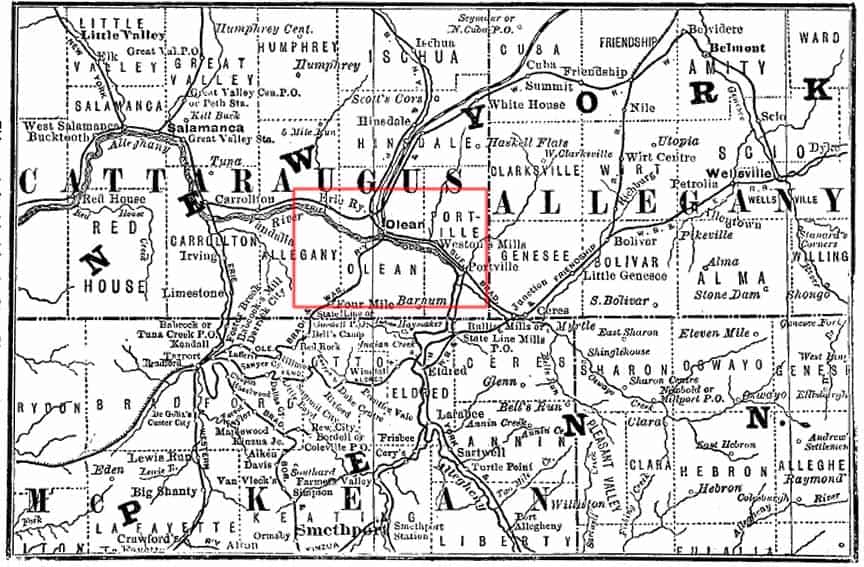

OLEAN, NEW YORK

Olean is a city in Cattaraugus County, New York. Olean is the largest city in Cattaraugus County, and serves as the financial, business, transportation and entertainment center of the county. Originally the entire territory of the county of Cattaraugus was called the Town of Olean formed March 11, 1808. As population allowed the county was split in half and the top half was called “Ischua”, and was taken off in 1812, a part of Perrysburgh in 1814, then Great Valley in 1818. Hinsdale formed in 1820, and Portville, in 1837, leaving the current boundary of Olean that lies upon the south line of the county, near the southeast corner. The area remained sparsely populated until 1804, when Major Adam Hoops acquired the land and gave it its modern name. [Wikipedia]

Select Timeline:

1812: Lambert Whitney was born at St. Johnsbury, Vermont on October 10, 1812.

1833: The influx of immigration during the decade ending in 1840 was not very extensive. Among those who arrived within the period indicated, who subsequently became prominent citizens, were Lambert Whitney, M.D., in 1833, who still resides here, having practiced medicine for forty-five years.

1834: Lambert Whitney united in marriage with Miss Sallie Senter.

1837: Lambert Whitney granted a diploma by the Medical Society of the State of New York in January, 1837

1837: Birth Lambert S. Whitney (son) born 23 July 1836, NY, and died in 1917.

1838: Lambert Whitney elected a justice of peace in Olean, NY and served in that office in all, twelve years.

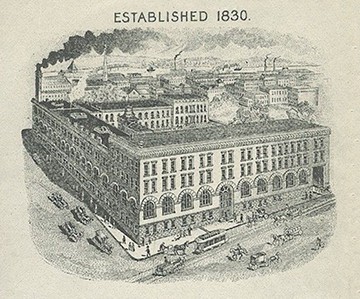

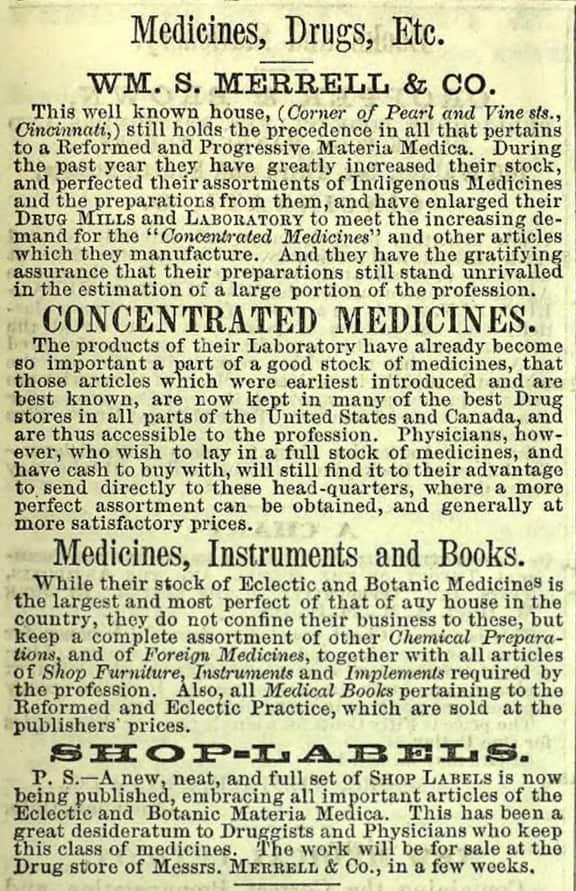

1839: Dr. Lamber Whitney agent for B. Brandreth’s Vegetable Pills.

1838: Russell M. Whitney, second son of Dr. Lambert Whitney, was born in Olean, April 6, 1838. With the exception of seven years in the U.S. army, his life has been spent in Olean. In June, 1867, he married Lydia S. Smith, of Northampton, N.Y. He is an extensive manufacturer of wagon hubs. Like is father Mr. Whitney is a respected citizen and prominent in political affairs. – Historical Gazetteer and Biographical Memorial of Cattaraugus County, N.Y. edited by William Adams

1853: Lambert Whitney was chosen to represent his town on the Olean Board of Supervisors.

1860: The people of Cattaraugus County elect Lambert Whitney to the office of county treasurer, which responsible position he filled acceptably and well for three years.

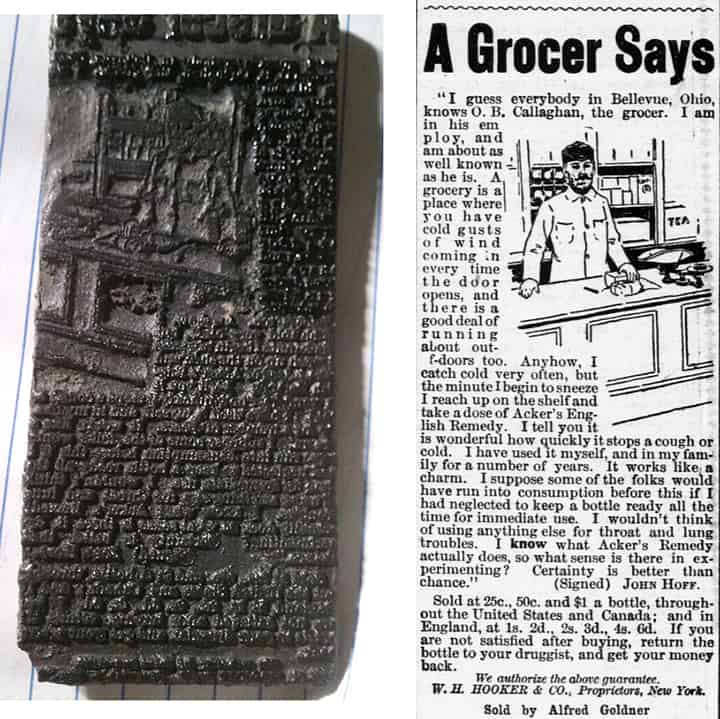

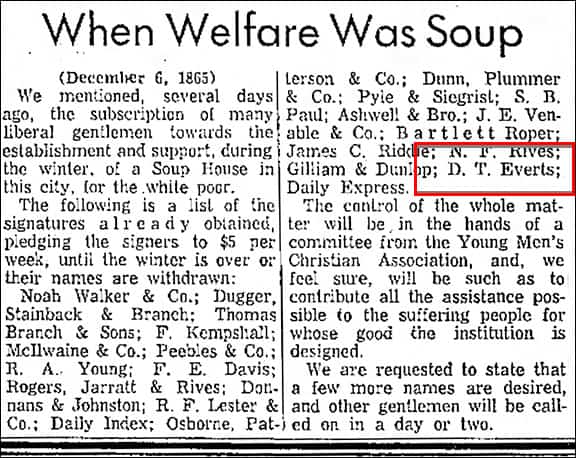

1865: Earliest mention of Dr. Whitney’s Bitters (see last advertisement in post).

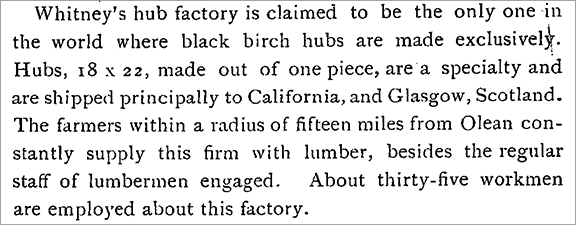

1874: The Olean Hub Factory was established in 1874 by Lambert S. Whitney. In 1875, Russell M. Whitney, brother of the original proprietor, was taken into the concern as a partner, and in July 1878, the latter, purchasing the interest of the former, became sole proprietor. The principal articles manufactured are black birch hubs, which have been quite extensively used by STUDEBACKER Bros., the well-known wagon manufacturers of South Bend, Indiana, and other large wagon manufacturers. Capacity, 124,000 hubs per annum. Hands employed, 15.

Whitney Brothers hub factory later grows to about 35 work men. I doubt the son Lambert S. Whitney was making a bitters. His father would have undertake this endeavor. They had a factory on Union Street in Olean, NY

1880: Lambert S. Whitney, Oil Production – 1880 United States Federal Census

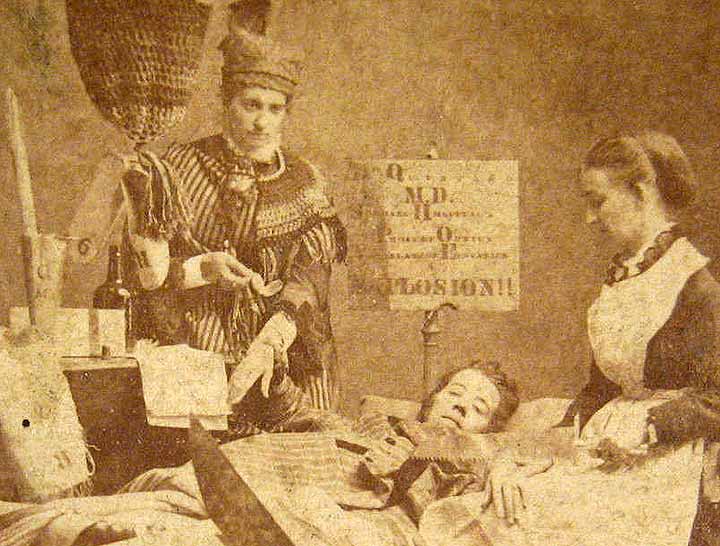

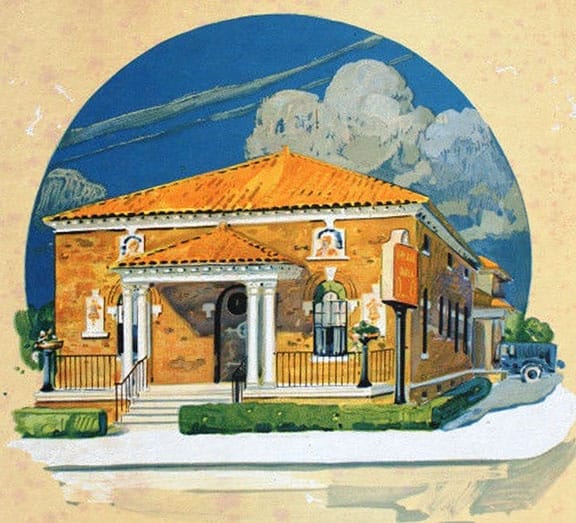

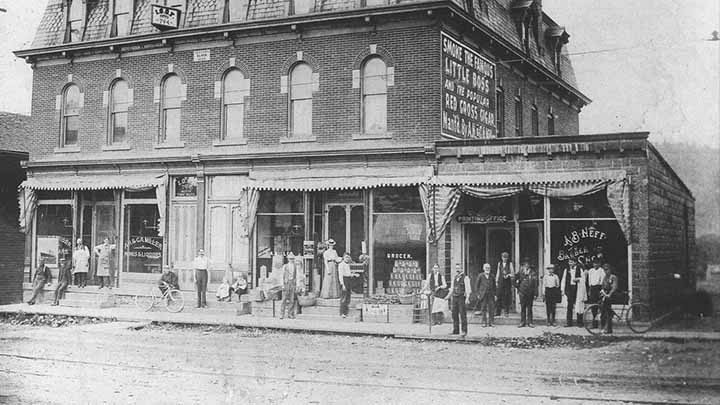

1893: Miller Block in the Village of Allegany (see picture below). Circa 1893-96 – History of Cattaraugus County

Just a neat period image of the Miller Block in the Village of Allegany Circa 1893-96 – History of Cattaraugus County

1901: Dr. Lambert Whitney death 0n July 31st, 1901.

1906: Lambert S. Whitney, farmer – Olean, New York City Directory

1912: “A Good Liver” Dr. Whitney’s Bitters advertisement (see below). – Times Herald, Olean, New York, October 17, 1912

“A Good Liver” Dr. Whitney’s Bitters advertisement (see below). – Times Herald, Olean, New York, October 17, 1912

1917: Lambert S. Whitney death.

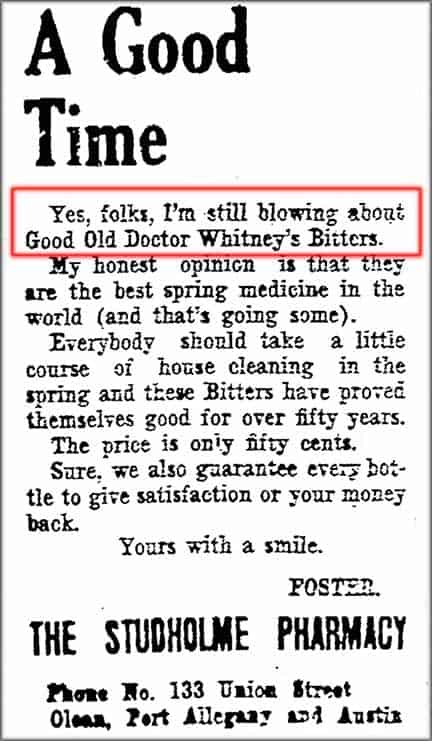

1919: “A Good Time” Good Old Dr. Whitney’s Bitters advertisement (see below). – Times Herald, Olean, New York, May 1, 1919

“These bitters have proved themselves good for over 50 years”

“A Good Time” Good Old Dr. Whitney’s Bitters advertisement (see below). – Times Herald, Olean, New York, May 1, 1919

1920: Studholme Pharmacy now to be Olean Drug Company (see below) – Times Herald, Saturday, July 24 1920