O c t o b e r 2 0 1 3

Thursday, 31 October 2013 (Halloween)

3.25 inches of rain since midnight. Heavy stuff coming. Wow. Hope is stops by tonight.

F., Nice Halloween postcard on PRG (see home page). The resemblance is scary. – Ken Previtali

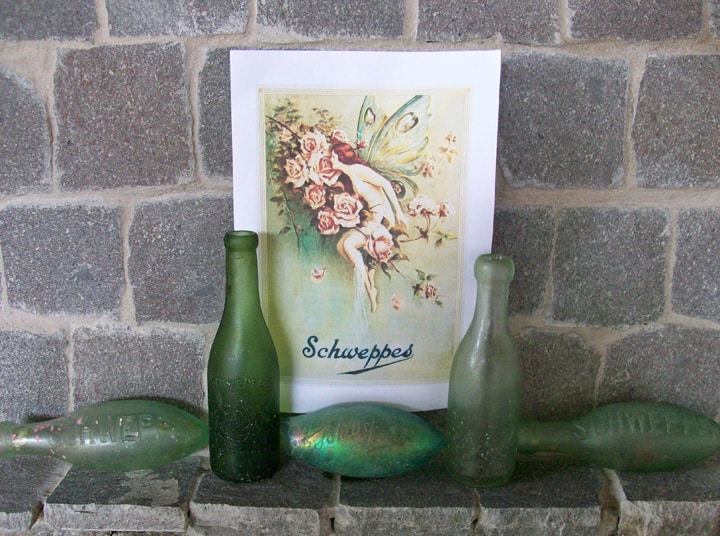

CLOUDS CORDIAL post just updated with information on Dr. Hiram Wilber Cloud from Evansville, Indiana. Thanks to Brandon Smith for lead.

Wednesday, 30 October 2013

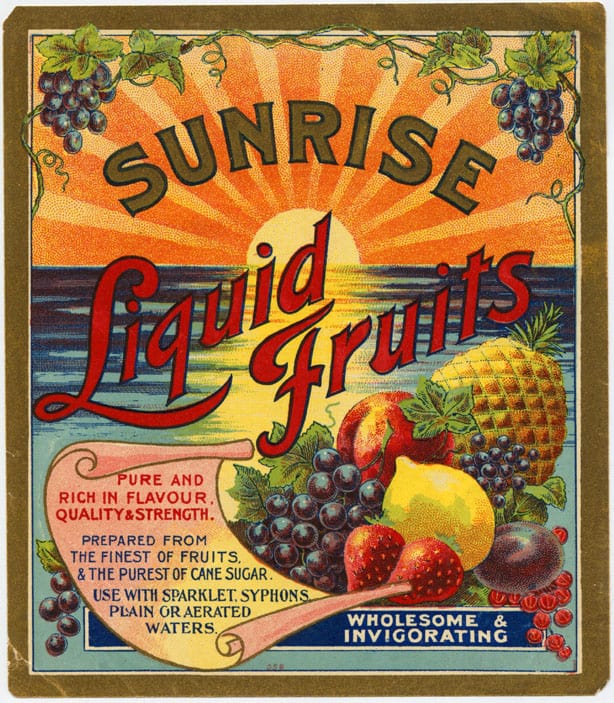

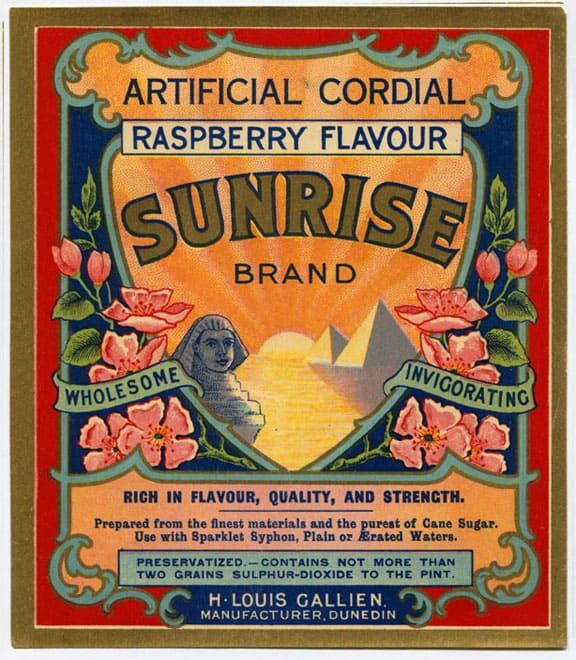

GM from rainy San Antone. Two nice ‘good morning’ Sunrise advertisements.

Tuesday, 29 October 2013

Leaving Miami for San Antonio. Closer to home. Headed over to look at John’s auction which ends tonight.

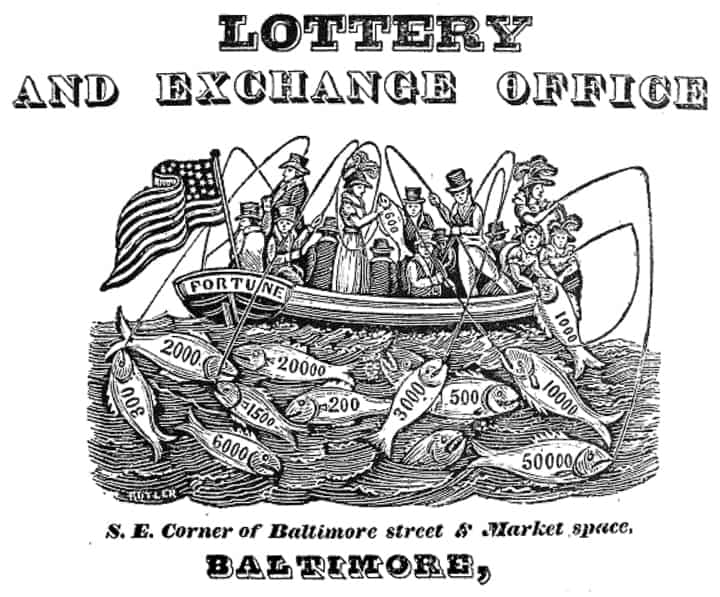

I like this advertisement illustration from an 1833 Baltimore City Directory.

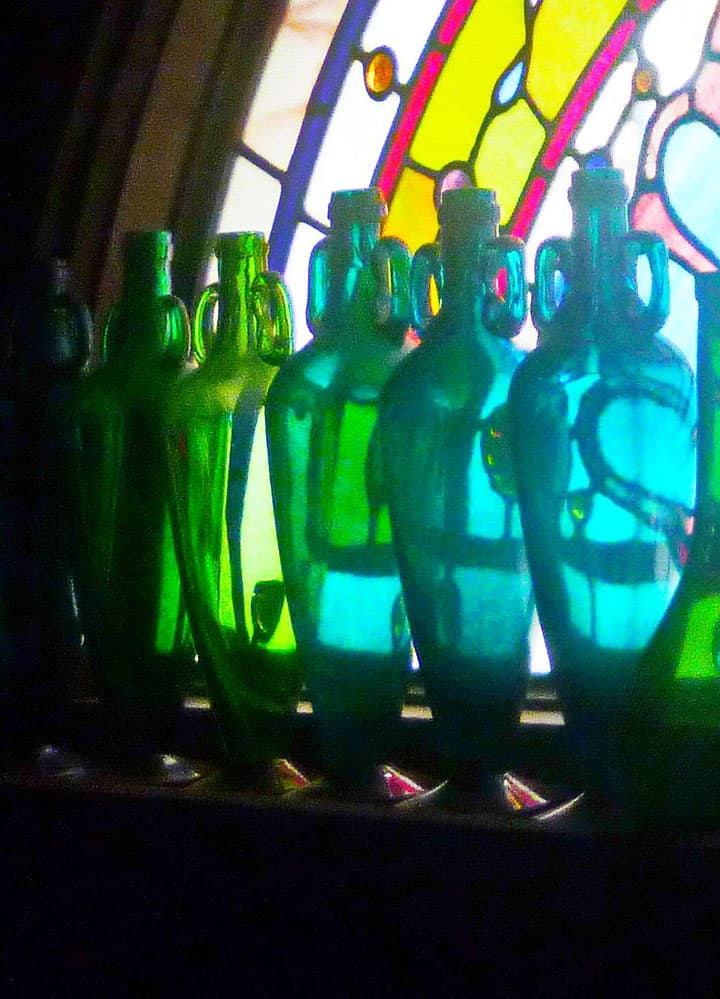

Updated: Historical Canteens – Canteen Figural Bottles

Monday, 28 October 2013

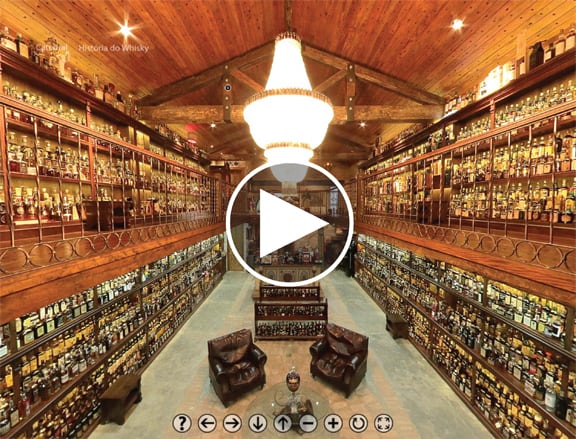

Off to Miami here shortly for business. Please make SURE you visit Catedral do Whisky. When you do, be patient and go deep in to it. Hit some of the prompts and boxes for details of cabinets. Pretty amazing. From Abel Da Silva who turned me on to this collection:

“Thank you very much for posting Jose Roberto Briguenti’s whisky collection on your site. He is in the earth moving and construction business in Brazil. He is one of the new Brazilian Millionaires.”

Sunday, 27 October 2013

Ahh… back at Peach Ridge.

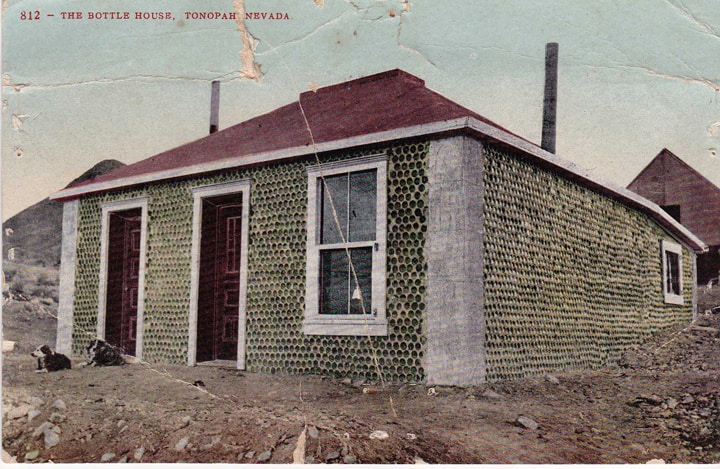

In from Ken Previtali. “Enjoyed the post on upcoming article in Bottles and Extras on Tonopah, Nevada bottle dig. Tonopah rang a bell and sure enough, it was a postcard of a house made entirely of bottles (at least the walls), and it was in Tonopah, NV. Postcard probably 1915 or so. Wonder how many were ginger ale bottles? The dogs look comfy.” Read: The Diamond Ginger Ale House

Read More: The Beer Can House – A Houston Landmark

Read More: Thailand’s Million Beer Bottle Temple

From Rick Simi: Noticed your post on the bottle house in Tonopah. Rhyolite Nevada had at least three bottle houses in its history. Goldfield Nevada still has a partial bottle house standing on the outskirts of town (as of 5 years ago). Here’s a link to the Rhyolite stuff: Tom Kelly’s Bottle House

Friday, 25 October 2013

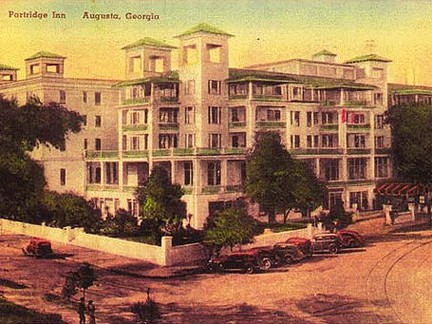

Looking forward to returning to Houston tomorrow. Miss my bottles. Off to Miami Monday and San Antonio Tuesday night. Nice to stay connected via email. Keep em’ coming. Sitting now posting at the bar at the historic Partridge Inn (above). Long week in Augusta, Savannah (love that city) and Athens, Georgia. Miss Elizabeth and my dogs too. Saw this cool truck (below) today at some backwoods joint. Apparently the bar scene from Sweet Home Alabama was filmed here.

On the other end of the spectrum, I toured the Ritz Carton Reynolds Plantation today. Man I wish I knew how to play golf! What a beautiful place!

Wednesday, 23 October 2013

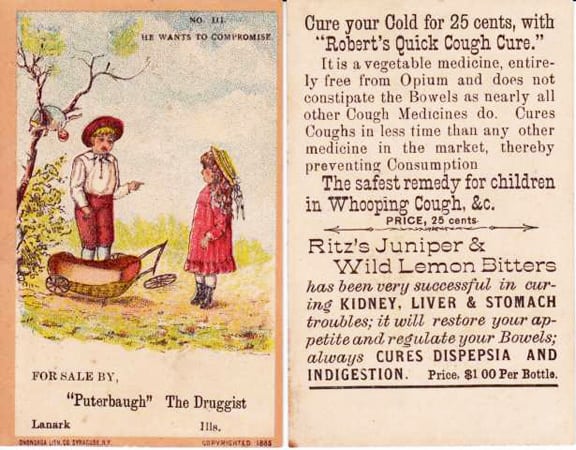

Ritz’s Juniper & Wild Lemon Bitters post updated with 3 Joe Gourd trade cards.

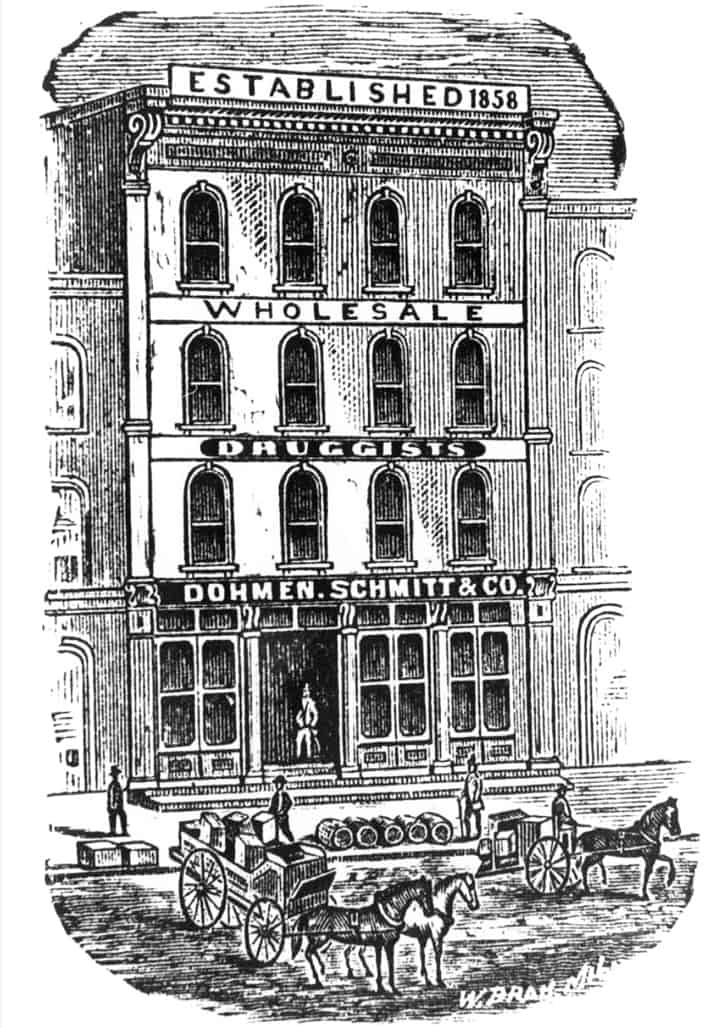

In Augusta, Georgia for business. Posting remote. Just completed the Frederick Dohmen Ritz’s Juniper & Wild Lemon Bitters post. I just love that name. Wish I had the bottle! Sent Joe Gourd an email to see if he has the trade card listed in the BB supplement.

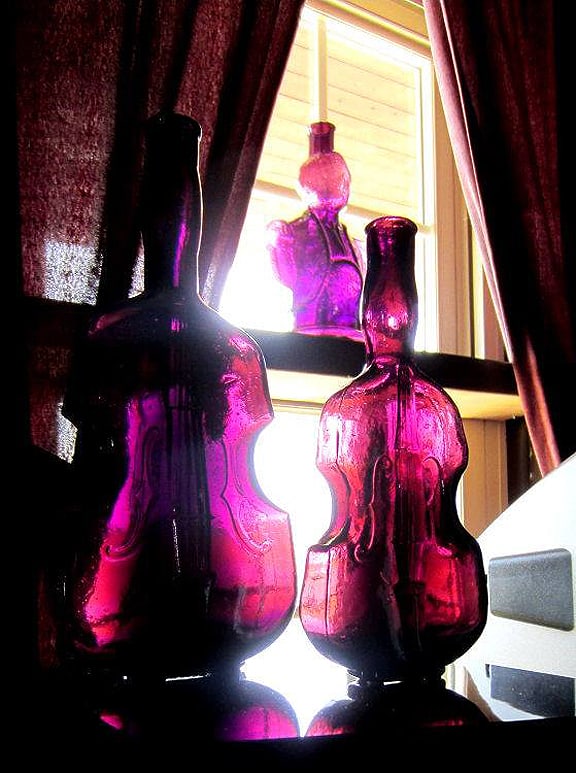

I like this photograph of a Drakes Plantation currently on ebay. Quite moody.

Monday, 21 October 2013

Cooler air coming. Out of town for a week so posting remote.

Picture of two J. Boardman Mineral Waters from left to right. positions 1 and 3 (center). Attached is a picture from the Manhattan Well Diggers article about Robert Biro’s collection. In the picture is a green and puce Boardman. – Richard Kramerich

Added image to J. Boardman & Co. – New York – Mineral Waters

Sunday, 20 October 2013

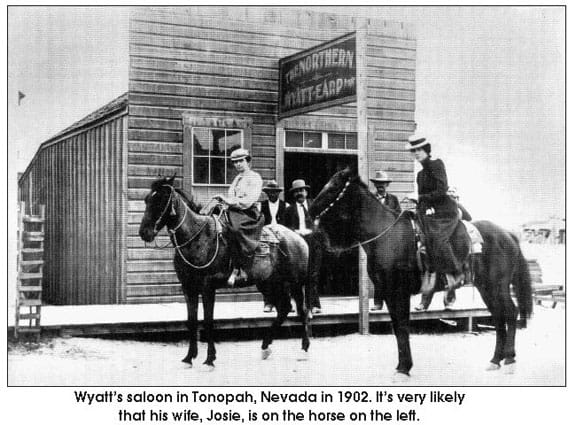

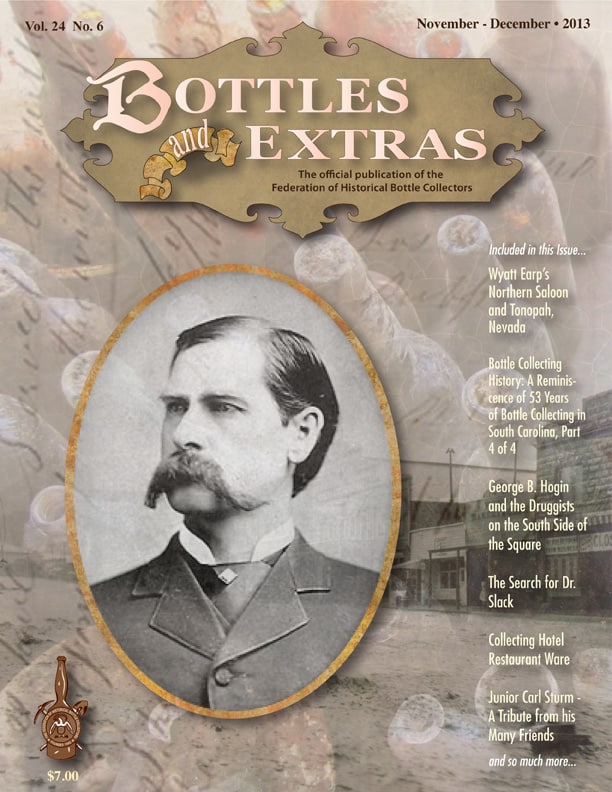

Cool picture I found online relating to the Wyatt Earp’s Northern Saloon and Tonopah, Nevada cover story in the next issue of Bottles and Extras by Michael Polak. Mike said regarding this pic, “what’s really cool about the photo is that it was taken just after the saloon opened in 1902, which wasn’t too long after the huge silver discovery in Tonopah. So, it was literally one of the very first saloon/structures in Tonopah.” Read: The Wyatt Earp Northern Saloon and Tonopah, Nevada Layers

Saturday, 19 October 2013

“From putting up only a few dozen for the retail trade about three years ago, their trade increased to 500 dozen in 1877, and will probably reach at least 1000 dozen for the present year.”

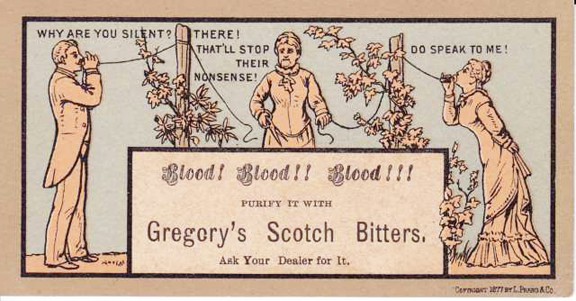

Great new material from Steve Ketcham including a labeled and embossed XR Gregory’s Scotch Bitters bottle and Young and Patterson Co. Almanac pushing same. Post updated.

Read: The Ginger Ale Page

Friday, 18 October 2013

Wow, so much going on. Look at this killer Reed’s Gilt Edge Tonic trade card on ebay now. Added to: Reed’s Gilt Edge Tonic Clocks post.

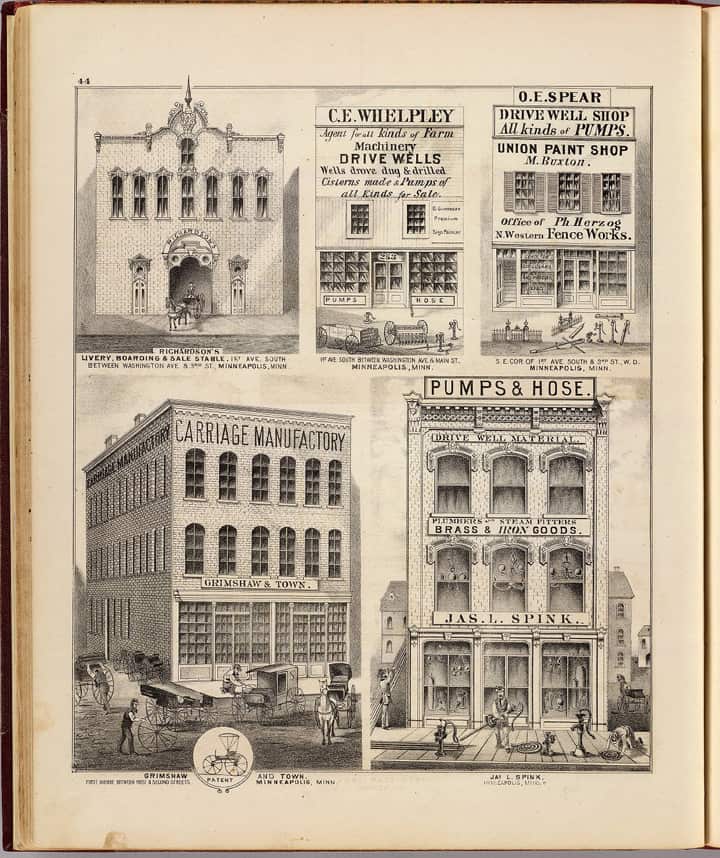

Here is the full page where you can see the Jas. L. Spink shop on the street level of the lower right image. Spink sold Gregory’s Scotch Bitters in Minneapolis.

The trade card series for Gregory’s Scotch Bitters came from bitters trade card king, Joe Gourd. What fascinates me so much with these three cards is that they are communicating by telephone. The cards are dated 1877. Bell patented the telephone in 1876! I like the mother clipping the wire.

Thursday, 17 October 2013

Back in the Bayou City. That’s good. Tired of hotels.

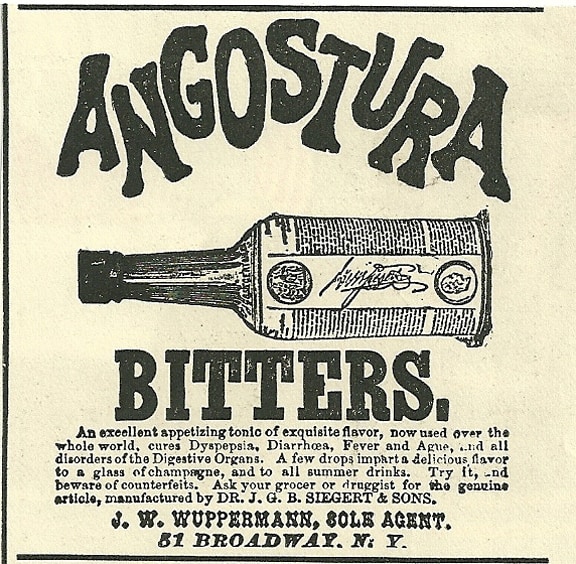

According to Ginger Ale authority Ken Previtali, there’s another piece to the Wuppermann story. During prohibition, they distributed ginger ale under the Angostura name. Note the “Fragrance of the Tropics” neck label (see image below) which could have been implying that the South American botanicals used in the alcoholic bitters recipe were part of the ginger ale flavor. How much of the bitters flavoring was actually used in the ginger ale is left to our imagination. The copyright date on the label is 1929. Post Updated

In from Bruce Silva:

Ferd: Not sure if I’ve discussed it or not, but I have been an avid firearms collector since the late 70s in addition to my first love bottles. I just posted and sold a very scarce, Webley and Scott .177 Tomahawk top break. During the course of conversation the buyer mentioned that a scammer had recently infiltrated the air gun classified arena and the website had been forced to post a warning to subscribers. Guess who and where was at the top of the warning list…?

Scam Alerts

There are several scams going on around the internet. The scammers are lurking around the various sales sites like eBay, GunsAmerica, craiglist, AuctionArms, and the various airgun forums including this one.

1. A scammer has been posting ads on this site using photos and text posted on overseas websites. The scammer posts under many names including but not limited to the following:

Cherry Thomas, Scott, Zuku, Scott Zuku, Zuku Scott, Zuku Dawson, Elliot Richard, Debora Thomas or Costie Fyke and others.

The scammers name is “Robert L Scott Jr.” from Clarksville Indiana. His contact information is listed below. He uses various email addresses typically from a gmail, hotmail, or yahoo account. He uses photos and text from UK websites like GunStar to post his ads. I have informed the Indiana State Police and Clarksville Police depts. about Mr. Scotts fraud activities as well as PayPal (who informed me taht they already were aware of Mr. Scott and has many complaints lodged against him already. I am continueing to block his access to my site and delete his ads but if you suspect that an ad is bogus check GunStar and ask the seller for additional original pictures and his personal contact information. Again, I apologize for any inconvenience this may cause my readers and I am working to resolve this issue. Thank you.

Scammers last known contact info:

Robert L Scott Jr.

124 S Clarks blvd,

Clarksville IN 47129

812-725-0770

502-640-5120

PayPal: rip24_2000@yahoo.com

Looks like our old buddy has diversified – Bruce

Wednesday, 16 October 2013

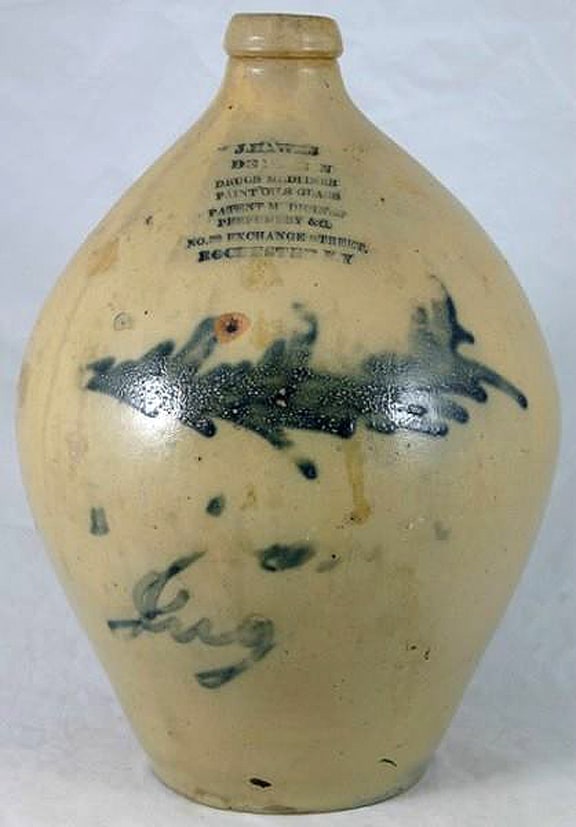

In reference to the Masury’s Sarsaparilla post, Mark Yates sent in this killer picture of a stoneware jug with graphics reading J HAWK’S… (Rochester, NY). Mark is unsure of image origination. Interesting that it does not say “J & T. Hawk’s”.

Did you know that ‘crossed keys’ symbolize the keys of the kingdom of heaven that bestow on saint peter the authority to bind. Why did I put this here today?

Pretty cool to find out that Frank Morgan (Wizard of Oz star), born Frank Phillip Wuppermann was from the Wuppermann family of Angostura Bitters. Read: The Wizard of Oz and Angostura Bitters

Tuesday, 15 October 2013

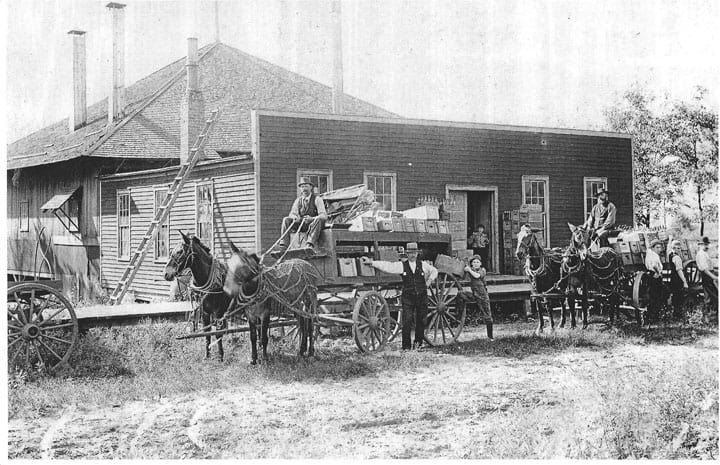

In Augusta, GA today for business. It is nice to receive letters or e-mails from people about previous posts. In this case it is in regards to the Mayer Bottling Plant (above) in Indiana. Read Mailbox.

Sunday, 13 October 2013

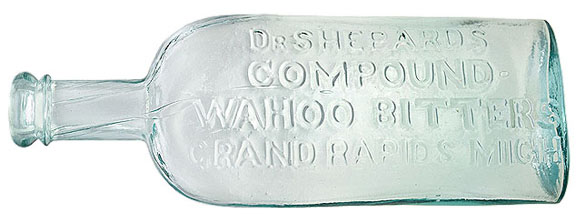

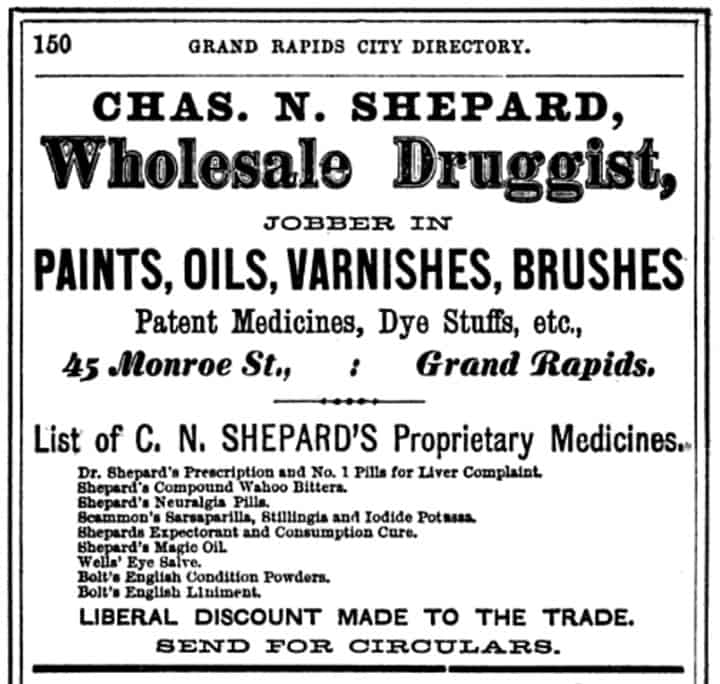

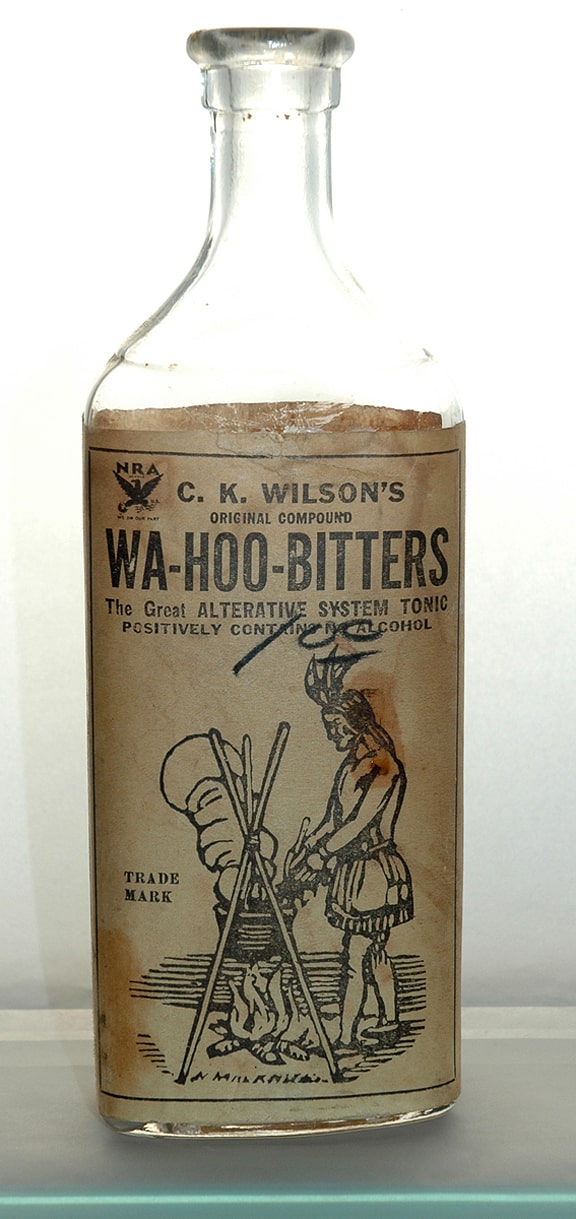

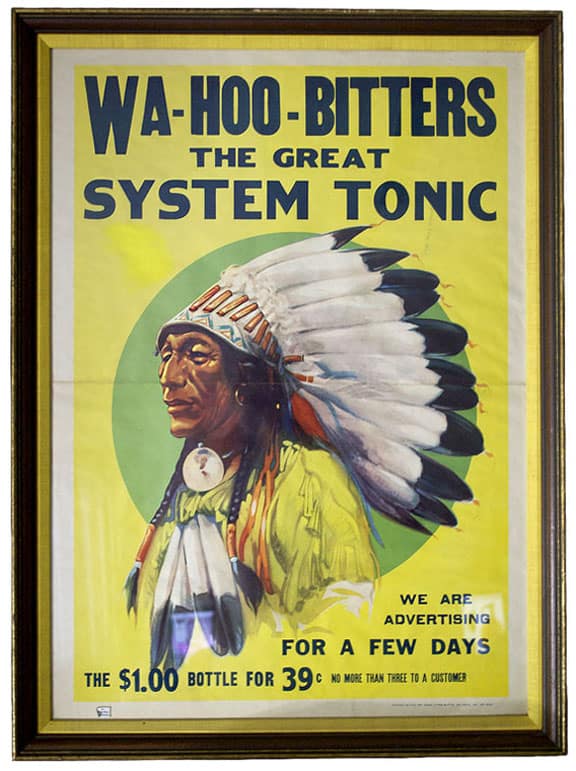

Look at this, almost 12″ tall, blue, dug, broken and re-assembled J T HAWK’S MASURY’S SARSAPARILLA COMPOUND from Rochester, NY. Mark Yates sent in the pics. Bottle in someone’s elses collection. Some say the finest medicine out there. Read: Masury’s Compound Extract of Sarsaparilla and Wau-A-Hoo

Saturday, 12 October 2013

Friday, 11 October 2013

Anybody catch that unlisted aqua color for extremely rare, Dr. Linwood’s Cabinet Bitters from Chicago that closed on ebay last night? Bill Ham alerted me to it and stated that he was preparing a revised catalog number and hand sketch based on the ebay photographs. Bill, let me know if you need any specific, exact measurements. I suppose I will develop a post on this brand. Early looking online indicate that this may be a bear. Read: Axel Lindskog attended the Wright & Taylor Old Charter Distillery Event

Pontiled, blue, MASURY’S SARSAPARILLA CATHARTIC – According to Robert Hinely, sold on ebay a few years back for $17,500. Read: Masury’s Compound Extract of Sarsaparilla and Wau-A-Hoo

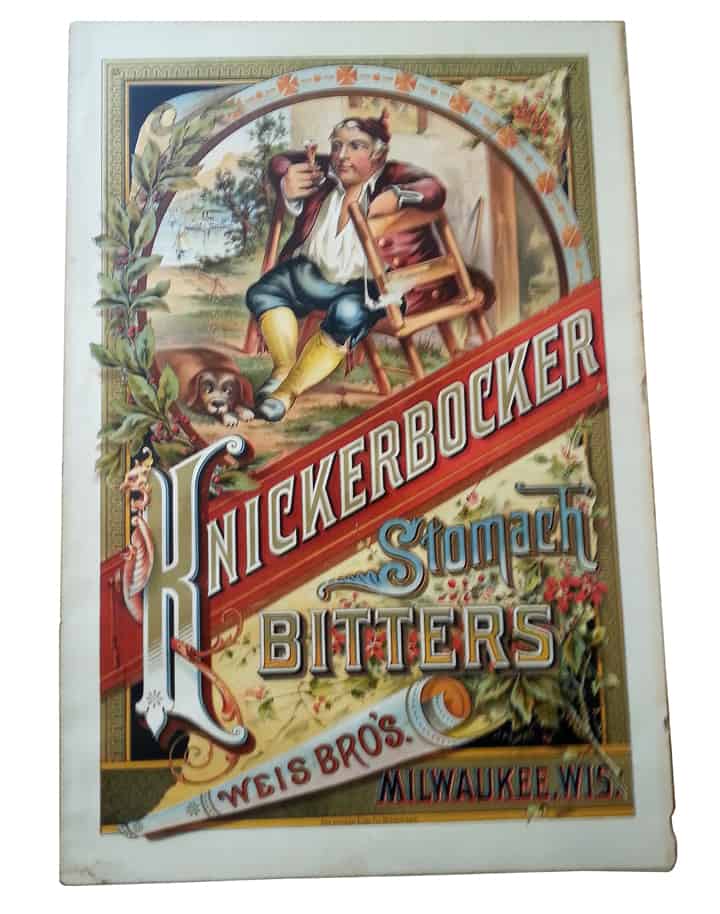

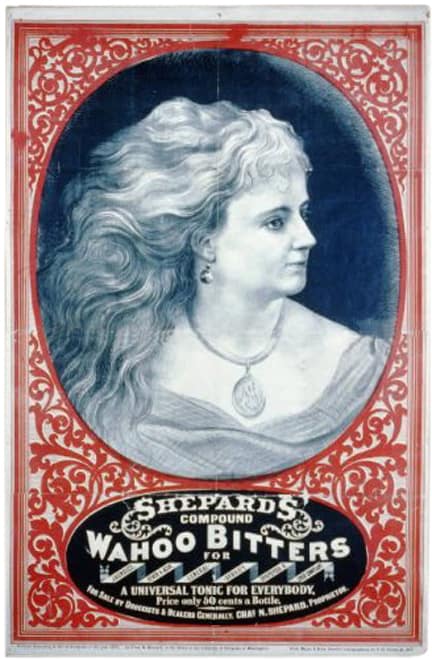

Weis Bro’s Knickerbocker Stomach Bitters sign advertisement – The poster was recently found as the backing to a 19th century painting by a Pennsylvania antique company. Pretty darn cool. Read: Lady’s Leg Series – Weis Bros Knickerbocker Stomach Bitters

Thursday, 10 October 2013

Up in Louisville today. You’all ever seen a Burwell’s Virginia Bitters?

Anybody watching that “RARE Peruvian Bitters NO MONOGRAM Old Amber applied top Western dug!” bottle on ebay? As it turns out, it is unlisted. Bill Ham has given it the following number:

P 65.8 PERUVIAN (au) / BITTERS // f // f // f //

9 ¼ x 2 7/8 (7 ¼) 5/16

Square, Amber, NSC, Applied mouth, 1 sp, Extremely rare

Like P 68, P 69. And P 70 except no monogram on reverse side.

Wednesday, 09 October 2013

Sorry, been away for a few days. Very busy getting the next issue of Bottles and Extras out.

I had the Peachridge Glass and FOHBC web sites transferred last evening to a shared VPS server which should help with site speed. The sites were getting a bit large. Think of it as going to a ball game and having a reserved seat somewhere in the stands. Now I am in the concourse section with the nicer seats and food. Not luxury boxes but this should be better.

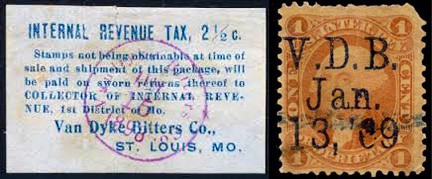

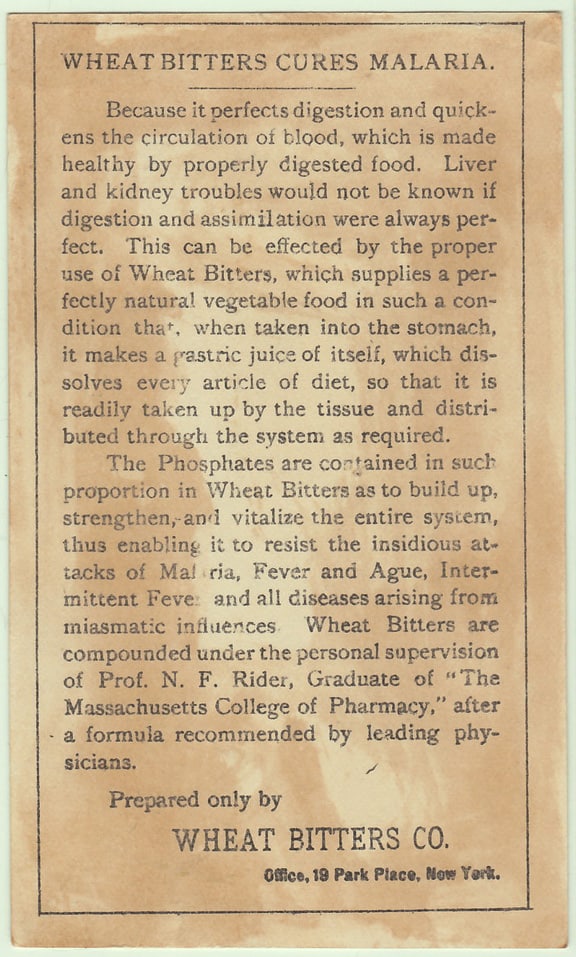

Very interesting, these new bitters in this 1881 Internal Revenue Record and Customs Journal document. This to me, since I am making comparisons, is like moving to an uncharted and deeper area of the ocean. Sure, we have great records by Carlyn Ring and Bill Ham in the Bitters Bottles books, but there is just so much more. Many more bottles still to be found. Much more research.

Saturday, 06 October 2013

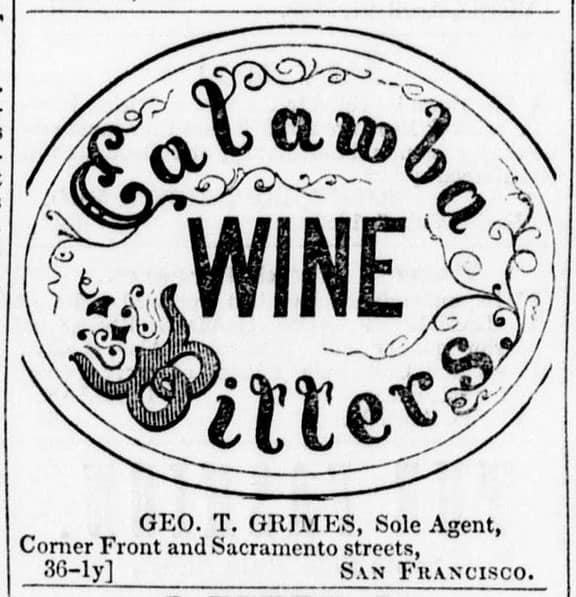

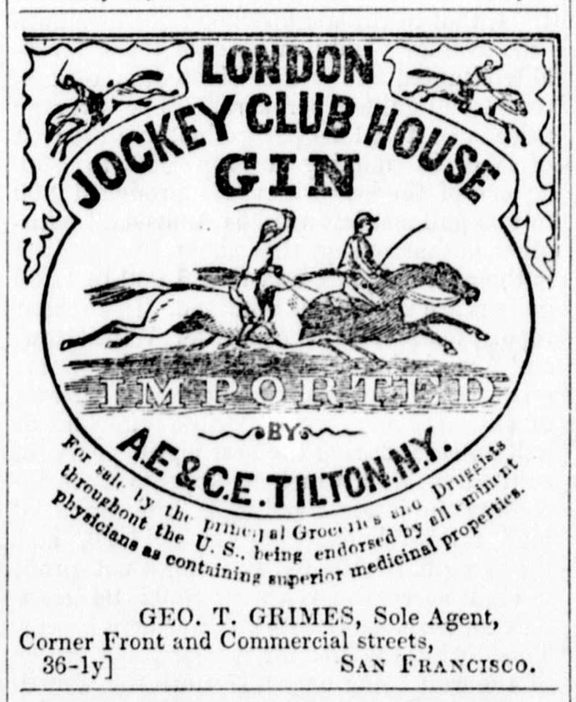

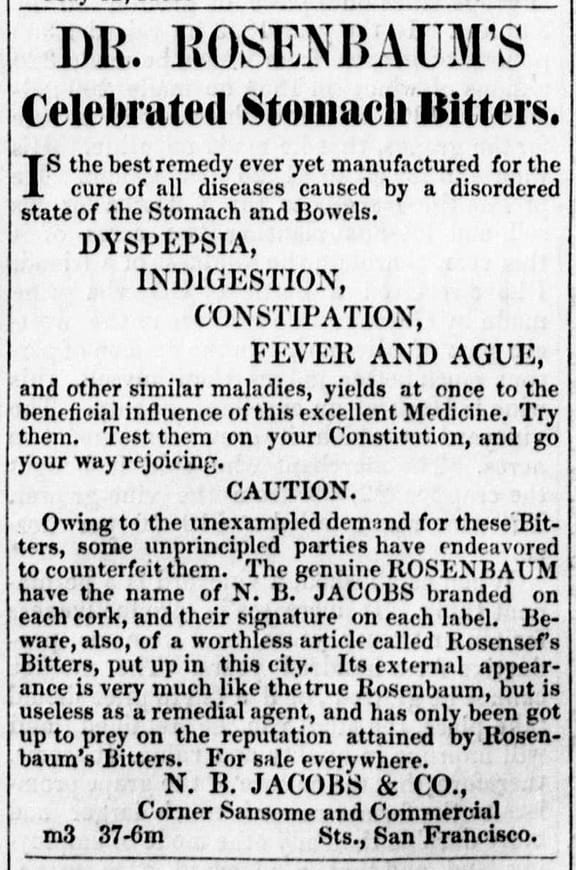

While poking around looking for advertising for Sands Sarsaparilla, I came across these three newspaper advertisements on the same page of The Hunter (San Francisco) in 1860. Catawba Wine Bitters, London Jockey Club House Gin and Dr. Rosenbaum’s Celebrated Stomach Bitters.

Friday, 04 October 2013

Really like this “MASURY’S SARSAPARILLA COMPOUND / J.T. HAWK’S ” over on ebay. Sucker is hammered. Read: Masury’s Compound Extract of Sarsaparilla and Wau-A-Hoo

This barrel is now for sale. Please contact me if interested. Read: Elusive Brent, Warder & Co. barrel found in Antique Mall.

Thursday, 03 October 2013

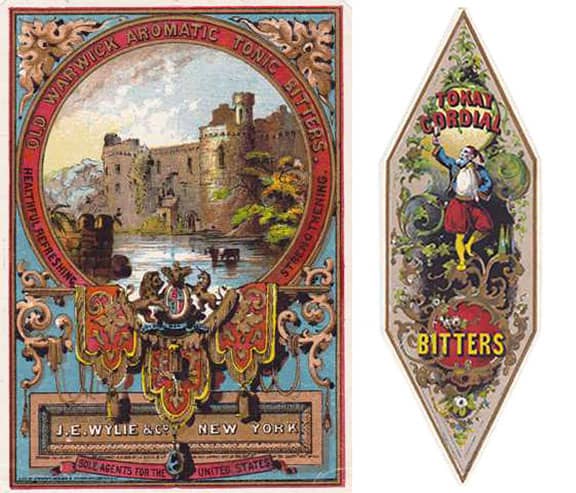

Tokay Cordial Bitters UPDATE. Read: What is Tokay Cordial Bitters?

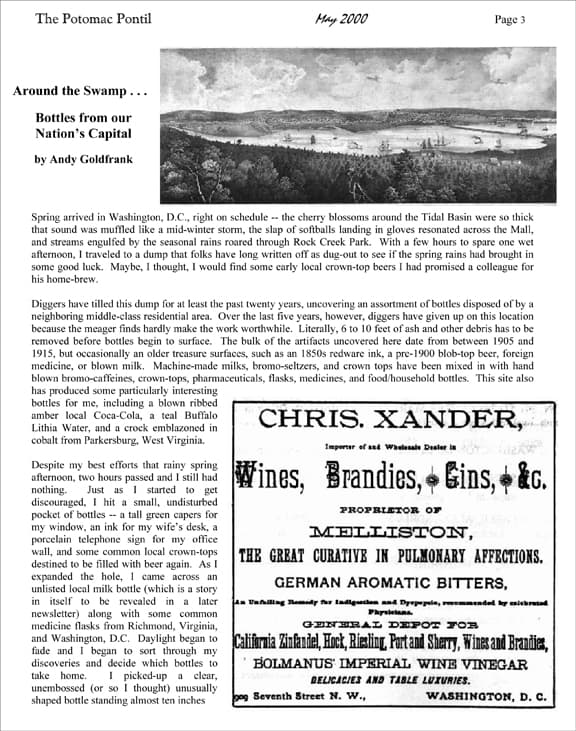

Ferd — Interesting post. At home, I do have an 1880s or so hock-ike wine shape in a light yellow with a seal stating “TOKAYER”. When I get home this evening, I can post an image or send it to you as an image via a message. My bottle was found at a mountain house hotel dump, dating 1860s to early 1890s, in the Hudson River Valley near Newburgh, NY. Take care, Andy (Goldfrank)

Wednesday, 02 October 2013

A couple of teases to start off the morning. Both unlisted Bill.

This UPSETS me to No End…. You think they could leave their web site servers on.

This UPSETS me to No End…. You think they could leave their web site servers on.

Due to the temporary shutdown of the federal government,

the Library of Congress is closed to the public and researchers beginning October 1, 2013 until further notice.

Tuesday, 01 October 2013

A new month. Waiting for the first sign of autumn. Could be this weekend.

Updated the Coca Bitters post with a very low res file of a possible printer’s proof of the Coca Bitters logo from the Joe Gourd collection. Read: The Mysterious Coca Bitters – New York.

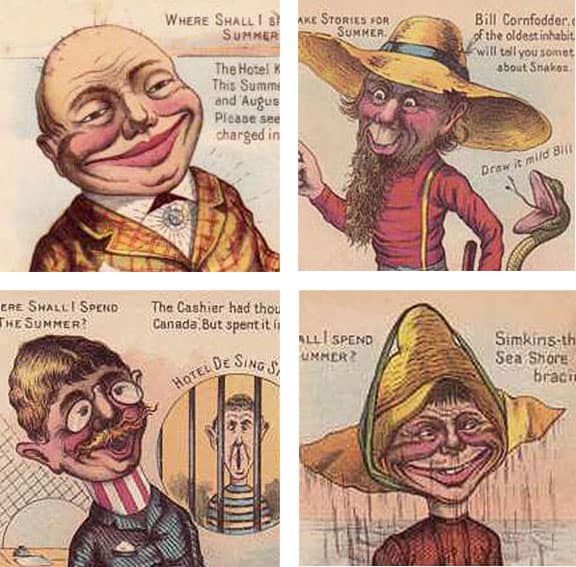

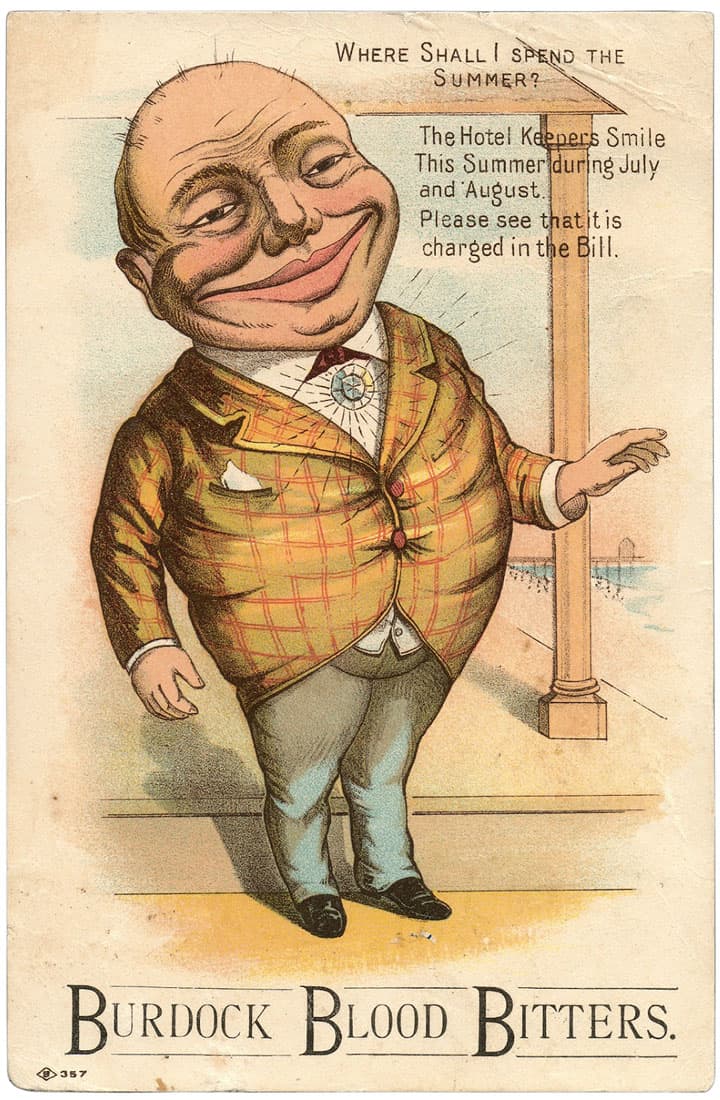

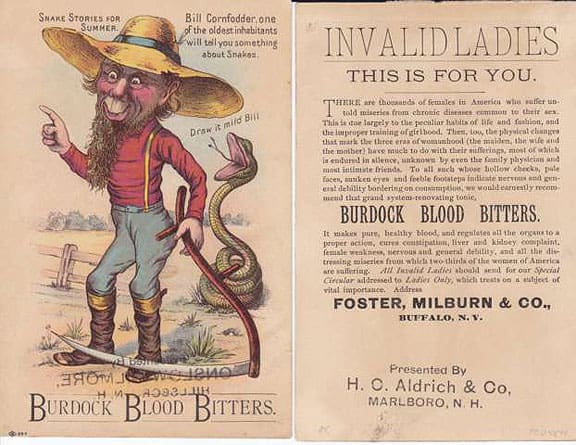

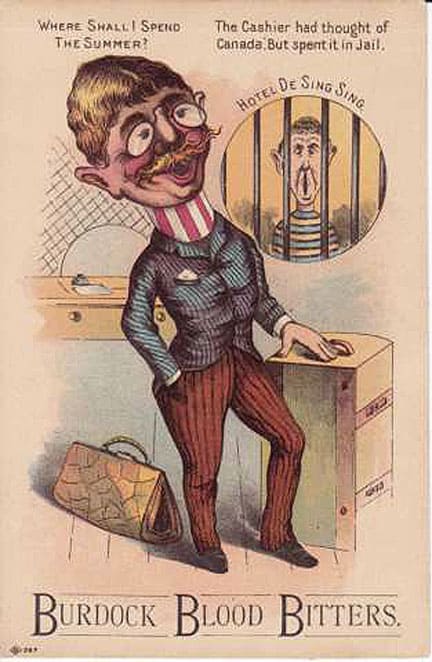

Joe also sent art for four Burdock Blood Bitters trade cards from the “Where Shall I Spend The Summer?” series. Read: “Where Shall I Spend The Summer?” – Burdock Blood Bitters.

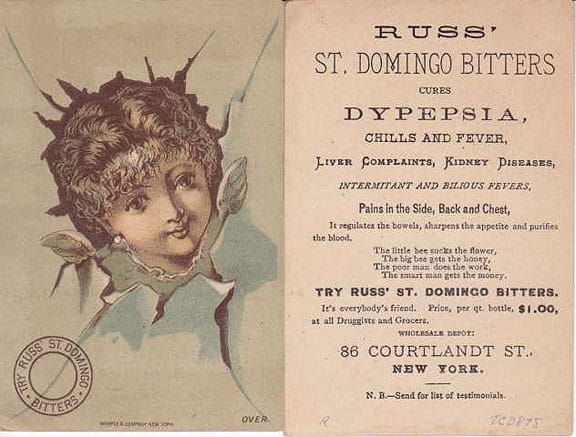

The mate card for the Russ’ St. Domingo Bitters incoming from Joe Gourd. Did not realize that there were male/female versions of cards.